The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore (12 page)

And I know that I wished Lydia had been there to hear me.

What may this mean? Language of man pronounced

By tongue of brute, and human sense expressed?

—

Eve, to Satan,

Paradise Lost

G

wen: help me. Yes, help me. Have you ever acted? Have you ever considered acting?

There’s a crucial speech in scene three of

Woyzeck

that I cannot possibly extirpate from the play, as it would have to be if the role could only be played by a chimp. For the role in question I had previously cast a relatively bright but of course speechless young chimp named Markus, but I have realized, and not without pain, that he is unsuited for the part, which is a small one but very important. I cannot cut the speech, and I cannot conceive of any plausible way of getting a chimp, an ordinary chimp, to deliver it. I’ve got no choice but to cast a human. It’s the part of the Showman—a charlatan, a snake-oil salesman—who musters up a festival crowd that includes Woyzeck and Marie. He has a horse that he claims can tell the time and communicate it by stamping his hooves. Anyway, his speech is too thematically important to entrust in the mouth or hands of a nonlinguistic animal. I need a human actor. You wouldn’t have many lines, I promise. Well, one big speech and a couple of little ones. Just come to our rehearsal this afternoon, see what you think. I can’t double-cast Leon in the part. It would be confusing. I already have him cast in the role of the Doctor. Leon

has a massive stage presence, which is why I only want him playing one part. Obviously I don’t mind casting across gender. I’m already casting across species. Please. Fine. Sleep on it. Consider it seriously, though. Here, take this. It’s a copy of the play. I urge you to give it serious consideration. You’re not badly suited for the stage, Gwen. You cut a striking figure, you have such a crisp, clean, beautiful voice. I’m not trying to flatter you. Give it some thought, that’s all I ask. You’d be great. I’m not crazy. Really.

I’ve just realized that I have come a long way in my narrative without bothering to describe myself. Physically, I mean. The basics. I wouldn’t want people to go on picturing me as an ordinary chimp.

On August 20 of this year I will be twenty-five years old. Years of bipedal standing and walking have straightened my spine, lengthened my legs and stretched my torso, and I now stand an upright four feet and one inch, which is short for a human being but basically towering for a chimpanzee. I groom myself meticulously; captivity has not made me slovenly or careless with my hygiene. I brush my teeth twice daily. I have no hair. Over ten years ago a rare but benign condition called universal alopecia caused all of my hair to fall out. I don’t mind my hairlessness. As a matter of fact, I like it. I love the feeling of my smooth nude limbs slithering between the freshly laundered sheets of my bed. I admit that I am somewhat overweight at one hundred and eighty pounds. I also admit to the surgery. Obviously I wasn’t born with this nose. I will later tell you about how a cosmetic surgeon gave me the nose job to end all nose jobs: he gave me a human nose. I think my human nose harmonizes beautifully with my surrounding chimp face. If you look very closely you can still trace the pale perimeter of scar tissue around my nose. Today I simply threw on this ratty old bathrobe, but, even in captivity, I usually take enough pride in my appearance not to

dress too sloppily. My clothes are getting thin and threadbare at the elbows and knees, but even a cursory examination of my wardrobe reveals my tasteful and elegant fashion sense. I keep asking for new clothes, and the research center keeps promising them to me and then forgetting (or ignoring) their promise. I have to have my clothes specially tailored because my frame is of such irregular proportions. For instance, my arms are longer than my legs.

Would you like a glass of wine, Gwen? Leon convinced them to let me drink wine, but they forbid me hard liquor. I know it’s not yet noon, but in my enforced retirement, I’m long past feeling the oppressive obligation to remain sober in the daytime. Why bother?

I have struggled with the demons in the bottle ever since they first seduced me. I struggle with them, and usually I let them win. So what? Imagine this: it’s as if there’s a hideous grating noise constantly roaring in your head, and alcohol muffles it a little. Why should I be made to feel embarrassed or guilty or ashamed when I imbibe? The world’s got its own problems. Who is the world to judge? Like most drunkards, I feel most alive when I’m killing myself. You would not so opprobriously condemn me for always wanting to drown my brain in wine if you knew how easily my mind races headlong into dangerous places without it, if you could feel how my palms ooze sweat, how my stomach recoils, how my heart flutters in my chest like a wounded bird when I am not drunk. If you ever have children, tell them they must always be drunk. Drunk on love, drunk on poetry, drunk on wine, it doesn’t matter. This world is too goddamn painful to waste a second of your existence sober.

Onward, then.

One day (it must have been, what?—November?), one day in the fall of a year that must have been around 1989, at the end of the

day, Lydia carried me out of the Behavioral Biology Laboratory on the third floor of the Erman Biology Center in the northeast corner of the main quad of the University of Chicago campus, away from my cage and away from my nights of jabbering with Haywood, wrapped in my fuzzy blue blanket, my arms wrapped around her neck. It was November, definitely November, and already murderously cold outside. Lydia was wearing a black wool peacoat, a knit cap, and a green flannel scarf tucked into the breast of her coat. The serpent of winter had bitten Chicago and bitten it bad, injecting it with the icy venom that whistled and shrieked through the city’s veins and arteries. It was time for streams dribbling from gutter pipes to solidify in midbraid, time for sooty snow and sludgy sidewalks. It was time for thick blankets. It was time for hats and boots. It was time for mugs of warm, viscous liquids to be sipped beside the soulful pulse of a fire, time for comfortable armchairs and good books and ice-fractals to form on the exterior surfaces of foggy windows, time for the soporific interior calm of a Midwestern winter.

I had been in Lydia’s car only once, when she had spirited me away from the zoo many months before (or was it years?—I’ve no way of estimating how much time had passed). Her car was an inauspicious thing, four-doored, flat, aerodynamically designed, dark blue. Under the blanket I scratched my face against the coarse material of Lydia’s woolen coat, and I licked one of its hard plastic buttons. I felt her chest moving beneath it, sucking in and pushing out her breath. My bare feet stuck out from under the blanket and quickly became numb from the cold. She opened the passenger door of the car and placed me inside, swaddled in the front seat in my blanket. She drew the straps of the seat belt across me and buckled it, tucked the diagonal strap under my chin and the horizontal one over my knees, kissed the top of my head, and shut

the door. It was silent and deathly cold inside the car. Peeking over the edge of the dashboard I watched her walk to the driver’s side, open the door, get in, close the door, buckle up, insert the keys,

chuppitachuppita-FROOM

, and then she piloted us stop-and-go through the grid of narrow brown urban streets, past blinking constellations of multicolored lights and bundled-up pedestrians huddled at street corners waiting for traffic lights to change, past the glowing windows of clothing shops, their wares on display, the expressionless faces of fashionably clad mannequins gazing icily onto the street from their display windows. Some windows had already been festooned with the first strings of red and green lights that signal the imminent close of the calendar year. I tried to stand up in the car seat to press my face to the window, but Lydia reached over and gently pushed me back into my seat, keeping me safe.

We arrived at Lydia’s home. She parallel-parked in front of the door to her building on the side of the street, unbuckled my seat belt, and helped me out. The street was lined with trees whose winter-naked fingers clawed at the gray sky. The trees were planted in mounds of mulch and enclosed by tiny white fences, each one set in the middle of a rectangle of dead grass blocked out by paved walkways; and each walkway led to an iron gate and up four steps to a door in a long contiguous slab of four-story brick buildings. Lydia bore me across the walk, through the gate, up the stairs to the door of her building, through that door and into a hallway. Her door was 1A: bottom floor, first one on the left. Supporting my weight with one arm while using the other to turn the key in the lock and push open the door in the same motion, she said, “We’re home sweet home, Bruno,” and, like a surreal subversion of newlywed man and wife, woman carried ape across the threshold of 5120 South Ellis Avenue, Apartment 1A.

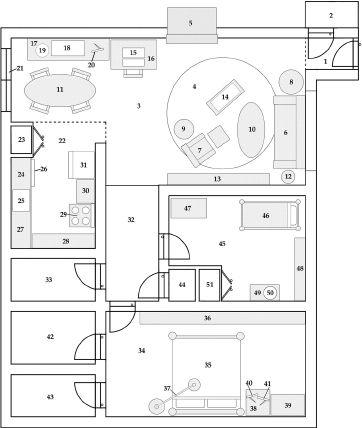

I should describe this space for you with utmost and delicate accuracy. Therefore, I now present you with a map of our apartment, which I spent all last night fastidiously drawing from memory. You may find it useful to consult as I take you on the grand tour.

5120 South Ellis Avenue, Apt. 1A, Chicago, IL 60615:

Residence of Lydia and Bruno

Lydia lived in a small but comfortable ground-level two-bedroom, two-bathroom apartment in upper Hyde Park on South Ellis Avenue, between Fifty-first and Fifty-second streets.

She set me down on the tiled floor of the vestibule (1), a small

dimly lit mudroom that provided a liminal space for psychological transition between the front door and the rest of the apartment. She kneeled and slid her feet out of her slushy winter boots and left them to dry on a mat by the front door, joining several other pairs of empty footwear lining the wall. She struggled out of her black woolen coat and hung it and her scarf and hat on pegs protruding from the back of the open door to the entryway closet (2). Her feet now shod in thick furry red stockings—had I ever seen Lydia barefoot?—had I ever before seen her in her stocking feet?—she took me by the hand and walked me into the combined living room/dining area (3), the largest space in the apartment. She clicked on a light, and a membranous corrugated paper globe hanging from the middle of the ceiling became illuminated from within, blanketing the room in soft gauzy light. The floors were of hard glossy wood, partially covered by a large circular area rug (4) that lay in the middle of the room directly beneath the paper lighting fixture; the rug, frayed and threadbare in its most heavily trafficked areas, was predominately burgundy and featured an intricate pattern of vines and flowers radially kaleidoscoping outward from the center, its circumference fringed with knotted tassels of string. The north wall, the longest in the room, is of bare brick, with a fireplace (5) embedded in the middle of it; the floor surrounding the fireplace is of inflammable gray-green granite tile, and it is protected by a glass-and-metal grate. The other walls are sheetrock, textured and painted regulation eggshell-white, and there are two vertical picture windows in the east wall that look out onto South Ellis Avenue, which, if privacy is desired, may be shrouded with red drapes that approximately match the rug. The furniture is homey but somewhat jumbled and mismatched. The smallness of the apartment has required Lydia to cram most of her furniture into this main living area, resulting in mildly unnerving crosscurrents of spatial flow. The tan leather couch pushed against the east wall

beneath the street-facing windows (6) matches the nearby armchair and ottoman (7), the two circular side tables beside the couch and armchair (8, 9) are of pine, and the ovular cherrywood coffee table (10) matches the ovular cherrywood dining table and chairs (11) in the far corner of the room, but these three different sets of furniture do not visually harmonize with each other. A floor lamp stands behind the couch in the southeast corner of the living room (12). A long and fully stocked bookcase (13) lines the south wall. On a small console a TV (14) perches awkwardly in the middle of the room, and a personal computer (15), along with a desk lamp and a tumultuous litter of papers, pens, and pencils, rests atop an architect’s drafting table (16). Various objets d’art personalize the room: a framed print of Marc Chagall’s

I and the Village

hangs on the north wall near the dining table, a dark and atmospheric Edward Weston nude above the worktable, and on the south wall above the bookshelf hangs a large rectangular painting depicting what looks like a writhing nest of eels slithering out of the green half of the picture and into the yellow; candles and primitive wooden effigies march across the top surface of the bookcase and across the fireplace mantel. Moving to the back of the room, we observe more closely the ovular cherrywood dining table and the four matching chairs. Beside the table is a waist-high oblong block of furniture (17) with three deep shelves locked behind glass doors; the bottom two shelves contain a miscellany of various knickknacks and oversize books, and the top shelf holds Lydia’s collection of tapes and CDs, its constituency reflecting her eclectic and generally excellent musical taste, combining elements of high culture (Dvo rák’s Cello Concerto in B minor), coffee-shop cool (John Coltrane’s

A Love Supreme

) and an American girlhood that blossomed in the early 1980s (Elvis Costello, Blondie, Prince, Talking Heads). On top of this is a stereo (18), with an LCD display of digital numbers, flashing, in a verdant undersea glow, an impossibly incorrect time. To

the left of the stereo rests a shallow burnished mother-of-pearl dish (19) into which Lydia, when returning home from work, empties the contents of her purse or coat pockets: keys, loose change accrued over the course of the day’s small financial transactions, etc.—joining pens, paper clips, and other coins already in the dish.