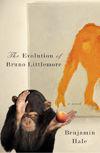

The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore

The

Evolution

of

Bruno Littlemore

Benjamin Hale

New York Boston

In memory of Jesse Barboza (1982–2007)

What I have learned from them has shaped my understanding of human behavior, of our place in nature.

—Jane Goodall

You’ll see it’s true,

an ape like me

can learn to be human too.

—King Louie,

“I Wan’na Be Like You (The Monkey Song)”

[The following manuscript contains the unedited transcripts of the memoirs of Bruno Littlemore, as dictated to Gwendolyn Gupta between September 9, 2007, and August 8, 2008, at the Zastrow National Primate Research Center, Eastman, GA 31024]

… But man, proud man,

Dress’d in a little brief authority,

Most ignorant of what he’s most assur’d,

His glassy essence, like an angry ape,

Plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven

As makes the angels weep; who, with our spleens,

Would all themselves laugh mortal.

—

Shakespeare

, Measure for Measure

M

y name is Bruno Littlemore: Bruno I was given, Littlemore I gave myself, and with some prodding I have finally decided to give this undeserving and spiritually diseased world the generous gift of my memoirs. I give this gift with the aim and hope that they will enlighten, enchant, forewarn, instruct, and perchance even entertain. However, I find the physical tedium of actually writing unendurable. I never bothered learning to type any more adroitly than by use of the embarrassingly primitive “hunt-and-peck” method, and as for pen and paper, my hands are awkwardly shaped and tire easily of etching out so many small, fastidious markings. That is why I have decided to deliver my memoirs by dictation. And because voice recorders detest me for the usual reasons, I must have an amanuensis. Right now it is eleven fifteen in the morning on a drably nondescript day in September; I am lying partially supine and extremely comfortably on a couch, my shoes off but my socks on, a glass of iced tea tinkling peacefully in my hand, and there is a soft-spoken young woman named Gwen Gupta sitting in this very room with me, recording my words in a yellow notepad with a pencil and a laserlike sense of concentration. Gwen, my amanuensis, is a college student employed as an intern at the research center where

I am housed. It is she who acts as midwife to these words which my mind conceives and my lungs and tongue bear forth, delivering them from my mouth and by the sheer process of documentation imbuing them with the solemnity and permanence of literature.

Now to begin. Where should I begin, Gwen? No, don’t speak. I’ll begin with the first time I met Lydia, because Lydia is the reason why I am here.

But before I begin, I guess I should briefly describe my surroundings and current predicament. One could say that I am in captivity, but such a word implies that I have a desire to be elsewhere, which I do not. If one were to ask me, “Bruno, how are you?” I would most likely reply, “Fine,” and that would be the truth. I know I’m well provided for. I like to think of myself not as imprisoned, but in semiretirement. As you already know, I am an artist, which my keepers recognize and respect, allowing me to occupy myself with the two arts most important to my soul: painting and the theatre. As for the former, the research center generously provides me with paints, brushes, canvases, etc. My paintings even sell in the world beyond these walls—a world that holds little remaining interest for me—where, I’m told, they continue to fetch substantial prices, with the proceeds going to the research center. So I make them rich, the bastards. I don’t care. To hell with them all, Gwen: I paint only to salve the wounds of my troubled heart; the rest is grubby economics. As for the latter—the theatre—I am preparing to stage a production of Georg Büchner’s

Woyzeck

, directed by and starring myself in the title role, which our modest company will perform in a few weeks for the research center staff and their friends and families. Broadway it’s not, nor even off-Broadway—but it satiates (in a small way) a lust for the spotlight that may be integral to understanding my personality. My friend Leon Smoler visits me occasionally, and on these occasions we laugh and reminisce.

Sometimes we play backgammon, and sometimes we converse on philosophical subjects until the smoky blue edge of dawn creeps into visibility through my windows. The research center allows me to live in all the comfort and relative privacy that any human being could expect to want—more, really, considering that my mind is free from the nagging concerns of maintaining my quotidian persistence in the world. I am even allowed outside whenever I please, where, when I am in my most Thoreauvian moods, I am allowed to roam these woods in spiritual communion with the many trees that are thick-trunked with antiquity and resplendent with drooping green mosses and various fungi. The research center is located in Georgia, a place I had never been to before I was relocated here. As far as I can determine from my admittedly limited perspective, Georgia seems to be a pleasant enough and lushly pretty place, with a humid subtropical climate that proves beneficial to my constitution. Honestly, on most days it feels like I am living in some kind of resort, rather than being confined against my will due to a murder that I more or less committed (which, by the way, could time be reversed, I would recommit without hesitation). Because this more-or-less murder is a relatively unimportant event in my life, I will not bother to mention it again until much later, but it is at least ostensibly accountable for my current place of residence, and therefore also for your project. I am, however, no ordinary criminal. I suppose the reason I’m being held in this place is not so much to punish as to study me, and I presume this is the ultimate aim of your project. And I can’t say I blame them—or you—for wanting to study me. I am interesting. Mine is an unusual case.

As a matter of fact, Gwen, I should apologize to you for my initial refusals to grant your repeated requests for an interview. Just speaking these opening paragraphs has made me realize that nothing I’ve ever yet experienced better satisfies my very human desire for

philosophical immortality than your idea of recording this story—catching it fresh from the source, getting it right, setting it down for the posterity of all time: my memories, my loves, my angers, my opinions, and my passions—which is to say, my life.

Now to begin. I will begin with my first significant memory, which is the first time I met Lydia. I was still a child at the time. I was about six years old. She and I immediately developed a rapport. She picked me up and held me, kissed my head, played with my rubbery little hands, and I wrapped my arms around her neck, gripped her fingers, put strands of her hair in my mouth, and she laughed. Maybe I had already fallen in love with her, and the only way I knew to express it was by sucking on her hair.

Before I begin properly, I feel like the first thing I have to do for you here is to focus the microscope of your attention on this specimen, this woman, Lydia Littlemore. Much later, in her honor, I would even assume her lilting three-syllable song of a surname. Lydia is important: her person, her being, the way she occupied a room, the way she did and continues to occupy so much space in my consciousness. The way she looked. The way she

smelled

. That ineffably gorgeous smell simmering off her skin—it was entirely beyond my previous olfactory experience, I didn’t know what to make of it. Her hair. It was blond (that was exotic to me, too). Her hair was so blond it looked

electrically

bright, as if, maybe, in the dark, her hair would naturally glow forth with bioluminescent light, like a lightning bug, or one of those dangly-headed deep-sea fish. On that day when we first met, she had, as was her wont, most of this magnificent electric blond stuff gathered behind her head just under the bump of her skull in a no-nonsense ponytail that kept it from getting in her eyes but allowed three or four threads to escape; these would flutter around her face, and she had a habit of always sliding them behind the ridges of her ears with her fingers. Futilely!—because they would soon be shaken loose again, one by

one, or all at once when she snatched off the glasses she sometimes wore. When Lydia was at work, her hands were endlessly at war with her hair and her glasses. Off come the glasses, fixed to a lanyard by the earpieces, and now (look!) they dangle from her neck like an amulet, these two prismatic wafers of glass glinting at you from the general vicinity of those two beacons of womanhood—her breasts!—and now (look!) they’re on again, slightly magnifying her eyes, and if you walk behind her you will see the lanyard hanging limp between her shoulder blades. On they went, off they came, never resting for long either on the bridge of her nose (where they left their two ovular footprints on the sides of the delicate little bone that she massaged with her fingers when she felt a headache coming) or hanging near her heart. Once, in fact—this was much later, when I was first learning my numbers—I had briefly become obsessed with counting things, and I counted the number of times Lydia took her glasses off and put them on again during an hour of watching her at work, and then I counted the number of times she tucked the wisps of hair behind her ears. The results: in a one-hour period, Lydia put her glasses on thirty-one times and removed them thirty-two, and she tucked the wisp or wisps of hair behind her ear or ears a total of fifty-three times. That’s an average of nearly once a minute. But I think these habits were merely indicative of a nervous discomfort she felt around her colleagues, because when she and I were alone together, unless she was performing some task demanding acute visual focus (such as reading), the glasses remained in their glasses-case and her hair hung down freely.