The Essential Book of Fermentation (20 page)

Read The Essential Book of Fermentation Online

Authors: Jeff Cox

Still, there was a time before pasteurization when tuberculosis, brucellosis, diphtheria, scarlet fever, and other deadly diseases were spread through poorly handled raw milk. Pasteurization was a huge step forward for public health after it was routinely introduced in the late nineteenth century. But with the advent of a better understanding of microbiology, better hygiene, modern milking techniques, and government regulation, raw milk, especially for cheese, is safer these days. Proponents of raw milk cheeses may also back the public’s right to drink raw milk today. In fact, I use raw whole milk from a licensed dairy here in California when I make

my daily kefir

, knowing that natural acidity in the milk, especially from the lactic acid produced by the kefir’s lactobacilli, protects me. Most pathogens like a pH nearing neutral to alkaline, while the kefir is in the protective range of around pH 4.0. Besides, California health officials monitor that dairy like hawks or it would be shut down pronto.

The Source of Cheese Flavors

By what magic is milk changed into the sensual, rich, and delicious food called cheese? The magic of microbial activity. In the first decade of the twentieth century, L. A. Rogers of the USDA’s Bureau of Animal Industry wrote a seminal paper entitled “The Relation of Bacteria to the Flavors of Cheddar Cheese” that pinpointed bacterial enzymes as the agents through which milk turns to cheese. Even when the bacteria are dead and gone, their enzymes remain in the curd, allowing for the continued ripening of cheese and flavor development for months and even years.

Today, we know it’s not always bacteria alone, but bacteria and yeast together that enhance the flavor of ripening cheese, just as bacteria and yeast produce sourdough bread and kombucha. In fact, cows make the milk, cheesemakers coagulate the milk, but microbes make the cheese. Dr. Antonio de Almeida of the Catholic University of Portugal studied a raw sheep’s milk cheese called Serra da Estrela and found six classes of bacteria (lactococci, lactobacilli, leuconostoc, enterococci, enterobacteriaceae, and staphylococci) plus yeasts. Analysis “revealed correlations between the major microbial groups present and patterns of volatiles generated.” These “volatiles” are the flavor and aroma components that make cheese into a multisensory experience, with layers of complexity. The bacteria and yeast act on large, long-chain molecules in the milk and reduce them to simpler molecules that give good flavor to cheese. Sugars, proteins, fats, and glycerides in the milk are turned into volatile acetic, propionic, isobutyric, and isovaleric acids, plus semivolatile fatty acids, free amino acids, and ethyl esters, the latter being responsible for fruity flavors in the cheese.

Yeasts join bacteria in producing the strong, pungent flavors and aromas of cheese. For example, with Limburger cheese, yeast first produces citric acid in the milk and then

Brevibacterium linens

converts the citric acid into the stinky substances we associate with Limburger. Either bacteria or yeast alone will ripen cheese, producing characteristic flavors, but it’s when the two team up that really interesting cheese results.

Food scientists have taken note of this and the genetic engineers have moved in. An article in the

Journal of Dairy Science

recently mentioned the “selective cloning and overexpression of the key enzymes involved” in cheesemaking. I investigated the term “overexpression” and found that it can mean a form of genetic modification. Lactic acid bacteria have a gene for manufacturing the enzymes that work on milk to produce flavor compounds in cheese. This gene has an “on” switch and an “off” switch. Genetic engineers find that switch and turn it on permanently in order for the gene to overexpress itself and keep producing enzymes even when they’re not needed. Does this lead to better-tasting cheese?

A study done at the Department of Food Microbiology at University College in Cork, Ireland, suggests not. The scientists took cheese bacteria and modified them genetically in various ways, turning on this gene, adding genes from other bacteria, and so on. They also made cheese using plain old natural

Lactococcus lactis

subsp.

lactis

(one of the main bacterial starters used in cheesemaking) as a control. The results? “Taste and chemical analysis showed that the control cheeses were of the highest quality.” Well, yes.

Of course, it’s not flavor the genetic manipulators are after—it’s consistency and cost economy. The summary of the conference notes from a recent seminar in France organized by Systems Bio-Industries states that “developing standard cheeses requires control of the diversity of microflora.”

Large cheesemaking operations seek product uniformity, but the diversity of microflora at work in curdled milk causes enormous variations in flavor and aroma. And so industrial cheesemakers remove all microorganisms through pasteurization, then add starter cultures to achieve uniformity. That’s great if simplified flavor is what you’re after. The seminar’s summary complains that the difficulty in identifying which bacteria produce which flavor compounds limits the ability to develop improved starter cultures. It suggests that electronic “noses” might assist the process. So, not only is nature’s own mix of microbes far too unwieldy and unpredictable for the industrial cheese gang, but the progress toward standardization will be augmented by electronic noses. Perhaps the end product should be fed to robots instead of people.

The best cheese flavors result from bacteria and yeasts working together on the sugars, fats, and proteins in milk. Some strains produce enzymes that convert milk sugar (lactose) to lactic acid. Others convert milk fat to flavorful free fatty acids. Others change proteins into their constituent free amino acids. Some of the most interesting flavors in cheese arise when strains of bacteria produce amino-acid-converting enzymes. These convert the free amino acids, especially methionine, into flavor-active sulfur compounds. Such complex actions happen on the molecular level, far too small to be seen by the naked eye. However, we can taste the results in the best organic farmhouse cheeses. Natural and organic cheesemakers treasure the microbes that make their cheese.

If you plan on making some of your own cheese, this material on milk should interest you. You want what nature, through her profligate microbial fecundity, can give you—unique cheese made in your own kitchen. The quest starts with the best raw material: organic raw milk. And if that’s unavailable to you, then organic pasteurized milk will do. Although it’s sterilized, you can recharge it with a culture of mixed bacteria and yeast put together expressly to make cheese; culturesforhealth .com sells kits for making just about any kind of cheese you desire. Or you can let the milk sit out and curdle naturally, drain off the whey and refrigerate it for other purposes, press the curds (or leave them as is for cottage cheese), and see what you get. That’s the way it has been done for thousands of years.

A Visit to an Artisan Cheesemaker

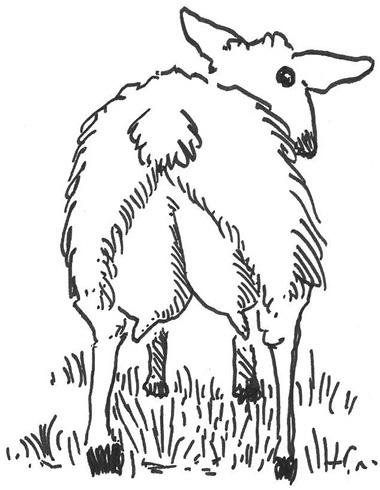

In 1986, Cindy and Ed Callahan moved from San Francisco, sixty miles north to Sonoma County, California, and the grassy hills along the Pacific Ocean. The water is too cold for swimming here, owing to the Japanese current that swings up the eastern side of Asia to Alaska, then down the western side of North America. It does produce a strong temperature differential between the cold water and the warm land that creates strong afternoon flows of onshore cold air and fog. The cool temperatures and grassy hills make it perfect sheep country, and so the Callahans began raising sheep on their thirty-five-acre farm, along with one hundred acres leased from a neighbor. Lamb was their business, and Callahan’s lamb soon became the standard for choice local lamb in the many fine restaurants of the wine country of Sonoma and Napa counties, and the San Francisco Bay Area to the south. After the lambs were born, they ran in the pastures with their mothers for thirty days, then were sold as very small premium lamb. The herd grew to four hundred animals—but after the lambs were sold, there was still a lot of milk. Wanting to expand the business, Cindy decided to try making cheese. She called her local county agricultural agent and asked him how to milk a sheep. “Milk a sheep?” came the incredulous reply. After trips to Europe and a perusal of the literature, and with the help of a Scottish woman who had worked at a sheep dairy in Scotland, Cindy, her sons Liam and Brett, and Liam’s wife, Diana, began California’s first sheep dairy in 1990.

Bellwether Farms cheeses, as her products are called, are named for the lead sheep (“wether,” originally a castrated ram) in any group, on which the farmer hangs a bell so other sheep can hear it and follow. Hence, that lead sheep is the bellwether. Bellwether’s cheeses rank among the most sought-after farmstead cheeses in the country. They are extraordinary. I first tried one—the Toscano, a Tuscan-style hard cheese about the consistency of a firm cheddar—in the early 1990s and had never before tasted a cheese that was so pure, buttery, delightfully nutty, and rich. Although the farm isn’t certified organic, the only difference between Cindy’s farm and an organic operation is that the feed she uses when pasture is unavailable is not organically grown. Everything else is as down-home and natural as can be. I spent a morning at Bellwether with Liam and Cindy, and they took me through the whole process. Now I’d like to take you through the process, too. Whether your interest is in making cheese, using it in recipes, or just enjoying it with a glass of wine and a crust of good bread, your knowledge and enjoyment will be enhanced by this peek into a real artisan cheesemaking operation.

I arrived at about seven when the morning milking was just getting under way. Liam, a large, stocky man of thirty-five, wearing alligator green and cream-colored Wellingtons, an off-white full apron, and a baseball cap with the Bellwether Farms logo, oversaw the operation. The ewes were brought in twenty-one at a time to fill the milking stanchions. A trough with cracked corn kept them occupied while the milking proceeded. The first ewes in didn’t walk all the way to the end of the line to start nibbling the corn, and so they were bumped and nudged along the stanchions by the rest of the group until all stations were filled. A sheep’s udder fills with milk into two defined football-shaped compartments joined together along one edge, with one teat angled slightly outward on each. With the ewes happily crunching corn, the milking was carried out by two workers who slipped the milking machine’s cups over each of the ewe’s two teats.

The sheep were mostly East Friesians, the northern European breed of preference. This breed gives about five pounds of milk a day from the morning and evening milking. The top 1 percent give eight-plus pounds. This is a lot for a sheep. According to Liam, the milk of Friesians has fewer solids but makes up for it in volume and in how long the sheep can be milked before they dry up. Mature ewes from three to ten years old will be milked for eight months each year. Then they’ll be impregnated and relax until lambing time in February to May. That freshens them for another eight months of milking. Also in the stanchions were Dorsets and a scattering of other breeds that give about two-plus pounds of milk a day—less milk but of a richer consistency, with more solids.

These sheep have fresh, green pasture grass until June, when the annual summer dry spell turns the hills their famous golden color. Green doesn’t return until the winter rains set in, usually in November. During the dry season, the sheep are fed supplemental conventionally grown alfalfa. Since cheesemaking has become the center of the farm operation, the herd is down to about 175 animals. Demand for Bellwether sheep’s milk cheese has become so great that the Callahans diversified by buying milk from a neighbor’s herd of Jersey cows and began making a selection of cow’s milk cheeses that have become as popular as their sheep cheese. “That took the pressure off this farm,” Liam says.

I noticed that the workers would finish milking a ewe, then return to her later for another go-round. “Sheep often have a second let-down, as it’s called, when more milk appears after the first milking,” Liam said. “It’s usually richer, and it’s good to milk the ewes out completely.” A few of the ewes who had just lambed had colostrum (in sheep, the thick, yellowish fluid nature provides initially to give young mammals a good start), but their lambs had died, and so their colostrum was milked out by hand, frozen, then fed to any weak newborn lambs to bring them to good health.