The Essential Book of Fermentation (15 page)

Read The Essential Book of Fermentation Online

Authors: Jeff Cox

A Visit to a Small Bakery

Country boy Lou Preston has made a name for himself as a winemaker. Preston wines are grown and vinified on Lou’s 125-acre ranch at the northern end of Dry Creek Valley, which runs northwest from the town of Healdsburg in Sonoma County, California. He started making wine at home in the 1960s and bought the ranch in 1973. He’s had a bonded winery, Preston Vineyards, since 1975.

At first he didn’t use insecticides, but soon got into a spray program that snowballed. “I found I was spraying more and more chemicals in the vineyards,” he says. “In the mid-1980s, I went cold turkey and stopped spraying,” and now he has forty-five acres of grapes certified organic by California Certified Organic Farmers (CCOF). “The reason I went organic is personal, it’s selfish. I didn’t want to be surrounded by a toxic chemical environment,” he says.

Recently I heard rumors that he was getting out of the wine business and devoting himself to baking artisanal loaves of organic bread. That’s not exactly right, I discovered. He’s reorganizing his wine business by downsizing it from 30,000 cases a year of thirteen varieties to 8,000 cases of seven varieties—and baking more natural-starter organic bread. “People who’ve gone the extra mile to be organic obviously care about their product. So customers know that the product is good and that the farming techniques used to grow the raw materials protect the environment,” he says. “The reorganization has been difficult,” he admits, but to watch the ease, skill, and enthusiasm with which he bakes shows that for him, it’s been worth it. Part of the reorganization has been to diversify his ranch. He’s planted a thousand olive trees for oil and cured olives, and is looking for other crops that host beneficial insects, are aesthetically pleasing, appropriate for Dry Creek Valley’s hot day–cool night climate, and add biodiversity to the ranch. “I’m working now to see if I can reproduce the Tabasco process,” he says. “If I get a lactic fermentation going in the peppers, the pH of the sauce goes from 5.0 to 4.0—and I read that pHs under 4.7 prevent the botulism toxin from forming.”

LET THE BAKE BEGIN

I showed up at Lou’s ranch at 6:30 on a recent Saturday morning to watch him bake, and found that I got there a few minutes before he arrived. I wandered a bit in the back where there was an old concrete kiva-style bake oven and an extensive organic garden with corn, squash, sunflowers, figs, cardoons, and much more, all patrolled by chickens clucking happily in the warm, early morning sunlight. Two kittens about ten weeks old came up to me, hoping I had a morning dish of milk for them.

Then Lou arrived and we went into his baking room, an extension off the winery’s tasting room, dominated by a beautiful masonry and brick oven built by the late Alan Scott.

Scott was an interesting character, and the one person who is perhaps most responsible for fine, small-scale bread baking in Northern California and around the country, for it was he who built the masonry and brick hearth ovens that he believed would become the centers of new communities of like-minded people. These communities are organically oriented, health conscious, and rooted in an environmental ethic that values the handmade, local, and artisanal over the cheap, mass-produced, and globalized.

“This book,” he wrote in

The Bread Builders,

“contains heaps of my enthusiasm for . . . those true baker-artisans . . . who are now successful family and community nurturers. Without nurture I do not think there can be nutrition, since nutrients, numbers, and other heady stuff can lack heart, whereas nurture, being from the heart, is the more powerful mover and shaker.” He believed that a fine bakery serves “our families, friends, and communities.” The book not only describes the ovens Alan built, but provides plans in case you’re ready to do backyard hearth oven baking yourself.

The oven Scott built for Lou Preston is large, with a four-by-eight-foot baking floor. “It takes about a square foot of space per loaf, so I can bake almost three dozen loaves at a time,” Lou says.

He peeked in the oven where a wood fire had just about burned itself out. The Saturday bake starts on Thursday, when the oven has cooled to about 300ºF from the previous bake on Tuesday. (He bakes twice a week.) Lou loads the oven then with about two and a half wheelbarrows full of oak, but doesn’t set it afire. It spends a day roasting in the oven so it’s nice and dry for Friday, when it’s set ablaze. The wood burns all day Friday, the oven temperature rising to about 700ºF. By Saturday, the fire has died down and the oven is about 475 to 500ºF, just right for baking.

The organic flour—white, whole wheat, and rye—is from Giusto’s Vita-Grain. On the previous day, Lou had made dough for our bake out of thirty-seven pounds of white unbleached flour and three pounds of a mixture of whole wheat and rye. To this he added twelve pounds of his wet natural starter, plus enough water, about twenty-eight pounds, to make a fairly slack dough that’s 74 percent water. Almost all bakers measure their ingredients by weight. It’s more accurate than by volume, and accuracy leads to consistency. “I make a sourdough country white bread from this,” Lou says. He’d shaped the dough into loaves and placed them in the folds of a couche—a baker’s linen—to proof, as the rising process is known in baker’s lingo. Since he filled the folds of the couche on Friday, they would overproof if allowed to sit out for a whole day, so he placed them in his walk-in cooler to retard the rising. An overproofed loaf has spent its yeast and carbon dioxide gas and won’t rise properly. There’s a bonus to keeping the dough in the cooler, too: “It develops flavor.”

HANDLING THE NATURAL STARTER

A natural starter is an active mix of dough and living microbes, mostly yeast, instead of the dry commercial yeast that most bakers use to leaven their bread. Because the ferment starts naturally in a mix of flour and water, it reflects the microbial population in the air of the bakery and gives the bread more of a taste of the place it’s from. Lou’s had his natural starter for ten years. “I learned about starters at the Culinary Institute of America [in the Napa Valley]. For an overnight starter, we used to put grapes into the flour and water so the yeast on the skins would colonize the starter and begin to ferment it. I later learned that natural starters take on the characteristics of where you make them and what you feed them. It takes months to get a starter of natural yeast and bacteria up and working strongly. Over that time, some strains die out, others grow stronger, until you get a stable mix of diverse fermentation organisms.” Interestingly, the Acme Bread Company in Berkeley uses a natural leaven that it has had for twelve years and that was begun with the yeast and bacteria on grapes—possibly from the same class at the Culinary Institute that Lou attended.

I watched, fascinated, as Lou cleaned out the floor of his masonry oven. First he scraped out the bulk of the wood ashes with a flat board at the end of a long handle. Then he scrubbed out the floor with a wet push broom, and finally mopped the floor with a wet rag on the end of a long pole. It all seemed so familiar, so ancient as well as modern, and I realized that if I could be transported back in time a thousand years or more, I’d be able to witness pretty much the same procedures being carried out.

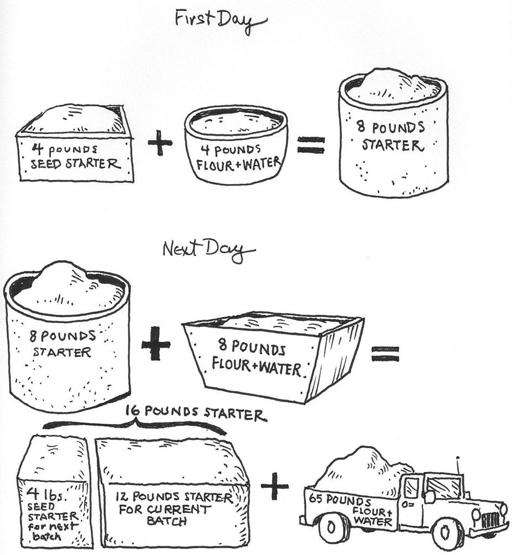

Lou told me how he keeps the starter going. When he makes dough, each batch takes twelve pounds of starter, or 15 percent of the total dough weight of about eighty pounds. He needs to save four pounds as the seed for the next bake. That means he needs to begin with sixteen pounds of starter. Starters need constant refreshing, and so to the four pounds of seed starter he adds enough flour and water to double it to eight pounds. The day he makes dough, he mixes this with four pounds of flour and four pounds of water, giving him sixteen pounds of starter. He takes twelve pounds for the bake and reserves four pounds to be the seed for the next bake. And so it goes, on and on. There are people in San Francisco who claim their sourdough starters have been going since the Gold Rush. But so what? As long as there’s

Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis

and

Candida milleri

in the air, anyone in San Francisco can make a sourdough starter that tastes the same as a starter that’s been going for 150 years. And starters can be made naturally anywhere in the country, not just the Bay Area—although San Francisco is known for the extra acidic and sharp quality of its sourdough bread.

Lou Preston’s starter procedure

GETTING THE DOUGH OVEN-READY

Lou wet-mopped the oven again and sprayed it with a hose with a long brass rod and nozzle that reaches all the way to the back. “This mitigates the temperature back there so it’s not so hot that it kills off the yeast in the dough before it’s had a chance to inflate the bread,” he says.

Now he takes a metal tray with five loaves of unbaked dough nestled in the folds of the couche and pulls the ends of the couche so it flattens out and there’s space between the loaves. He has two one-by-six-inch boards, one in each hand. With his left hand, he places the board vertically next to one of the loaves and expertly flips it to the right onto the board in his right hand, which is held horizontally. This he holds level and slides the dough with a quick, jerky motion onto a peel—the long-handled, flat-bladed wooden utensil used to slide loaves into and out of the oven. When he has all five loaves lined up on the blade of the peel, he reaches for his lame (pronounced

lamm

), which is a tool for slashing the top of the bread. It’s about five inches long and holds a curved razor blade that slips under the surface of the loaf as it slashes. Sometimes the dough will puff out through these slashes before it’s even placed in the oven. Usually, however, when the dough heats in the oven, the yeast furiously makes gas, which expands the bread up through the slashes. This allows for good expansion and has the added bonus of giving the bread a crustier surface area. One can use a sharp serrated knife, but I find the lame is the perfect tool for the job. Lou dips it in water between loaves to keep the razor edge clean. Elongated Vienna-type loaves are slashed with two slightly oblique slashes. Round loaves are slashed with three slashes that cross in the center, giving a six-pointed effect. Other round loaves are given a semicircular slash “so that the top pops up like a little hat,” Lou says. Once the loaves are slashed, he walks them to the oven, opens the door, slides them into the back, sets the peel aside, sprays the inside with the nozzle again (the steam helps the loaves achieve a crunchy, perfect crust), and repeats the process until all the loaves are in the oven. The loaves get steam only during the first ten minutes or so of the bake.

PAR-BAKED AND FULLY BAKED LOAVES

The loaves go into the oven at 7:30 a.m., and Lou says they’ll be finished in forty-five minutes. Because his winery visitors often buy loaves, and they are only oven-fresh on Tuesdays and Saturdays, he par-bakes some of his loaves, a method he learned from Nancy Silverton at the La Brea Bakery in Los Angeles. “You take the par-baked loaves out at twenty-five minutes and cool, then freeze them. When you get them home, pop them into a 450 oven for twenty or twenty-five minutes, until they look right and sound hollow when thumped on the bottom. You can hardly tell the difference from once-baked loaves.”

A number of Lou’s loaves come out at twenty-five minutes for cooling and freezing. He takes the peel and slides the loaves remaining in the oven into positions he knows from long experience will be the right places for them to finish a perfect bake. After a while, he uses the peel to retrieve the fresh, crackling loaves from the oven. They are a dark brown with all sorts of color variations in the crust and slashes that have expanded. “I like the darker-colored crust rather than a light one,” he says. “If I had more dough ready, this oven would be perfect right now. The second bake is usually the best.”

He selects a loaf and we tear it open, still steaming hot inside. It’s lightly sour (“It would be more sour if I took more time to let the starter develop after refreshing it,” he says) and, as I find out after I get it home, acquires an even sharper sour flavor when it cools. The flavor is incomparable, the crust a jingly, crunchy, nutty joy. The bread inside the loaf is hot and stretchy, still smelling of yeast and wheat. Lou hangs up his peel, and as the loaves sit on trays to cool, I can hear little ticking sounds as the crusts crack as they cool.

My mind is on the bread, which I know will make a perfect lunch when I spread it with runny, tangy Teleme cheese and eat it with a glass of Lou’s spicy, tart Barbera wine.

More About Natural Starters

Lou Preston’s fermentation added layers upon layers of flavors to his bread. His natural starter is now, after all these years, a carefully balanced ecosystem of yeast and bacteria, but to understand the sourness of his bread, I did some research into the bacteria that accompany yeast in starters. All starters, even a packet of commercial dried yeast, have bacteria associated with the yeast, although in a commercial packet of dried bread yeast, it’s probably not more than a few percent. Natural starters have much more bacteria, and thus tend to make sourdough-type breads. The bacteria are those lactobacilli that produce lactic acid, just as they do in cheese and yogurt, and

Acetobacter,

which converts the alcohol produced by yeast during the fermentation into acetic acid, the sharply sour kind of acidity one detects in vinegar.