The Essential Book of Fermentation (14 page)

Read The Essential Book of Fermentation Online

Authors: Jeff Cox

These test results are posted as to lot number, so bakers really know what they’re dealing with. Bakers also find out which wheat variety is used in their flour, where the wheat is grown, the name of the farmer who grew it, and how long the lot will be in stock before it’s replaced by a new lot.

“In the past, the problem with organic flour had been its variability,” Duffy says. “It’s usually produced by small companies with small mills and small storage facilities. So a baker buys flour grown by farmer X this week, and next week it’s another lot, grown by farmer Y. But lots vary tremendously, and this causes problems for bakers who want consistency in their high-quality loaves. Here at Cook, half of our entire wheat supply for six months is purchased and stored already, so we get more consistency, and each lot is numbered under our identity preservation program so the baker can check its characteristics and track it from farm to bakery.”

Besides the baker, the farmer benefits from the identity preservation program. “Small farmers, especially organic farmers, can’t make money growing wheat and selling it through brokers or to elevators. Wheat is a commodity with prices set so low the farmer gets beat up on price.” Huge factory farms can do it because they have economies of scale and are sometimes vertically integrated with big grain companies like Archer Daniels Midland and ConAgra. “But selling organic wheat is another story,” Duffy says. “Organic farmers are paid more. A hundredweight of conventional, commoditized wheat sells for about $5 at the farm. The organic farmer gets a 150 percent premium—up to $12.50 a hundredweight.” Cook thus has set itself up as a supplier to small artisan bakers looking for flour of a quality commensurate with their talent, bakers who want to produce bread with

terroir

.

An Organic Flour Supplier

One of the chief suppliers of organic flour to the artisan baking trade is Giusto’s Vita-Grain in San Francisco. “In 1940,” says Keith Giusto, the current owner, “my grandfather bought a whole grain bakery and health food store on Polk Street, and made a nine-grain bread. He milled his own wheat for it.”

(In an aside, he says his grandfather was captain of the country’s first professional soccer team. Maybe it was that good nine-grain bread that gave him the energy.)

“People would ask him, ‘How come your bread tastes so good?’ and they would offer to buy his flour. So he started selling flour and it became a big part of his business. In 1960, my dad and uncle found organic grain farmers and started selling organic flour—so we’ve been doing it for a long time.”

Keith is the third generation of Giustos in the business. He’s almost fifty years old and still hunting for new sources of organic wheat. “Tonight I’m going to Washington [state] to check on a new organic farmer,” he says. “With organics, you have to be a good farmer, and you have to be planting the right varieties. Our most popular flour is made from 100 percent winter wheat with a protein content of 10 to 11 percent. That’s just about right for artisan bread.”

Besides the organic flour business, Giusto runs a baking school in Petaluma, about an hour north of San Francisco. “People come from all over, some as far as Arizona, to attend these classes. They’re small, four-to six-person custom classes, and most of the students are professional bakers who want to learn more. We’ll educate you as deeply as you want to be educated about the whole process, from farm to mill to bakery,” Giusto says.

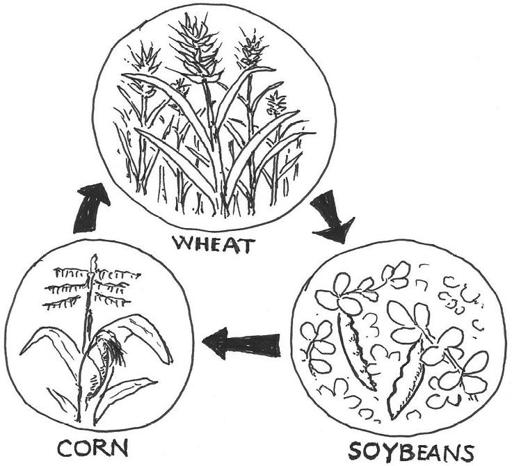

Typical crop rotation

Giusto is in a tight relationship with his organic farmers. “We’re loyal to our farmers and they’re loyal to us,” he says. “Try that with ConAgra and they’ll tear you up. For instance, five years ago, we started helping farmers find outlets for their rotation crops of corn and soybeans.” Organic farmers, as opposed to most conventional ones who use chemicals, rotate crops. They’ll follow wheat with soybeans, a legume that puts nitrogen and organic matter into the soil. The following year, there’s enough nutrition to bring in a crop of corn. Cornstalks are plowed under, and their decaying organic matter is sufficient to support a crop of wheat in the fourth year. The depleted soil is then revitalized with a crop of soybeans the following year, and the cycle begins again. This is sustainable farming. Most conventional farms, on the other hand, flood the land with chemicals to support the same crop year after year. These chemicals can destroy the microorganisms that dismantle crop residues into nutrients for subsequent crops to use. As one farmer who year after year plants “continuous corn” told me, “I plow the cornstalks down in the fall and plow them back up in the spring.” Because of the lack of life in the soil, the cornstalks don’t decay to feed the soil. Small organic farmers cannot guarantee buyers full production of wheat each year because of their need to rotate crops, and to make up the slack in wheat income, they need to sell their corn and beans. Giusto’s ability to find markets for their rotation crops helps them immensely.

The Taste of Maine in a Loaf of Bread

That’s a concept dear to the heart of organic baker Jim Amaral and his wife, Dolores Carbonneau, who in 1993 started Borealis Breads in the basement of the Pine Cone Tavern in Waldoboro, Maine. Interestingly, Amaral was a winemaker at Sakonnet Vineyards in Rhode Island, where he grew Pinot Noir, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and a white French-American hybrid called Vidal before starting Borealis Breads. The move from wine to bread isn’t that great a stretch, considering that both are fermentation products that are at their best when they’re locally produced and organic.

Amaral started with just twelve breads and twelve accounts. Today the business employs fifty-five people and annually buys a million pounds of flour that go into 1,440,000 loaves of bread baked at four retail and two wholesale bakery sites around Maine. He’s looking forward to the day “when we will have a range of breads made exclusively from Maine wheat varieties bred by Maine grain breeders. The wheat will be grown in Maine. The bread will be unique to Maine, using Maine techniques, Maine varieties, natural leavens from Maine bacteria and yeast, and all local resources,” he says. Of course, he’s talking about

terroir

. “I want people to eat my bread and say, ‘That’s Maine wheat,’” he says, just as people now associate certain tastes of wine and other foodstuffs with particular regions of Europe or California.

A real farmer you can call up on the phone or reach via e-mail

The idea of locally grown and baked bread is one of the key reasons why Borealis Breads is so successful—that, and being organic. “People aren’t just buying the bread, they’re buying the company,” Amaral says. “If I’m using local ingredients, people will buy that. Organic is important, too, but honestly, locally grown is most important and organic is second to that.” In addition, Russ Libby, the executive director of the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MOFGA), encouraged Amaral to “put a face on the product.” Amaral took heed and, with a $10,000 grant from the Maine Department of Agriculture, produced a series of “farmer cards,” similar to baseball cards but with photos of individual Maine farmers and recipes on the back. “We hand them out with every retail transaction,” he says. The cards have become wildly popular. I can see why. Brand loyalty is something the big agribusiness companies know all about. But when the brand is also a person, it’s an even stronger marketing concept. Look at Orville Redenbacher, Oscar Meyer, Betty Crocker, Colonel Sanders. When the person is a real farmer you can call up on the phone or reach via e-mail, brand loyalty becomes almost a family affair.

It hasn’t always been a million loaves and farmer cards, however. “When I started out,” Amaral says, “I began with four different organic loaves. People weren’t buying them. It was difficult. But that’s turned around. People now are paying attention to whether bread is organic or not. I give lots of credit to MOFGA and their leadership, but what has really turned the market around is the media attention on organics when the USDA issued its organic rules, and the fact that people know that organic on the label means there will be no genetically modified ingredients. Farmers—they’re terrified of GMOs. It could kill their overseas business.”

The process of achieving the goal of producing locally grown organic bread is well under way. Aroostook County in northern Maine, known these days primarily as a source of fine potatoes, “was the breadbasket of New England during the Civil War,” Amaral says. “We’re working with farmers there to grow hard red winter wheat with a protein content of 12.5 to 15 percent.” That high protein percentage is characteristic of wheat grown in northerly areas—a reason the northern part of the Great Plains of the United States and Canada is now the breadbasket of the world. When protein in flour is hydrated with water and kneaded, it forms gluten. The higher the percentage of protein in flour (or the “stronger” the flour, as it’s called), the more gluten can be formed. Gluten is the substance that makes bread elastic, stretchy, and able to swell with the gases released during fermentation, resulting in light, chewy breads with many air holes. Very high protein wheat—over 14 percent or so—can result in strong white flour with too much gluten, producing breads that are rubbery, dense, and tight. Wheat grown in more southerly climates has from 8 to 10 percent protein or less and is good for pastry, waffles, pancakes, cakes, and biscuits, but doesn’t have enough gluten to react to the gaseousness of fermentation by producing light, chewy bread. That’s why the baking powder griddle cake is associated with the South and the loaf of yeast-risen wheat or rye bread is associated with the North. All-purpose flour is so labeled because it’s designed to be good for all these kinds of uses and more. According to many sources, something like 11.5 percent protein is ideal in a white, unbleached organic flour destined to make ideal white bread. Whole wheat, on the other hand, can be stronger, with about 14 or 15 percent protein. Whole wheat contains everything in the wheat berry—the bran, which is the fibrous outer coating of the berry; the germ, which is the vitamin E–containing, nutritionally power-packed site of the embryo that would become a new wheat plant if sown; and endosperm (the white starchy part of the seed). When flour is milled from whole wheat, the tough bran is broken into tiny fragments that can slice through the long strands of gluten, deflating the air holes that make bread light, and creating a dense loaf. Therefore the extra protein in whole wheat is beneficial, for it will create more gluten that will overcome the effect of the bran.

Grains other than wheat don’t produce gluten, or very little. That’s why rye, barley, oat, and rice flours are always mixed with wheat flour—unless a dense flatbread is wanted.

Bread Boffo on Broadway

Amy Scherber began with a small bakery in the Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood on the West Side of Manhattan. Now just about everyone in New York City knows Amy’s Bread. There are three retail locations in Manhattan and her bread is sold in many stores around the city. From the beginning, she was determinedly organic, but it wasn’t easy.

“Organic hasn’t always been an easy sale,” she says. “Not all the customers want to pay extra for organic. Or they don’t understand what it is, so they think it sounds like health food, which they avoid. In New York, we are way behind the West Coast on the popularity and availability of organic products, but we have slowly developed a following for our products because they taste great and are organic, too.”

Given the difficulties, Amy could have made conventional bread, but “I like to use organic flour when I bake because I feel it has a positive, long-term effect on the soil used to grow the wheat, and on the sustainability of the land and the groundwater.” But taste enters into it also. “We make some delicious organic breads that are not sour or tangy,” she says. “I prefer a mild, earthy, wheaty, non-sour bread with my cheese, so that’s why I choose organic. I get those results with my organic flour.”

She buys her flour from Cook Natural Products, Giusto’s Vita-Grain, and Community Mill & Bean in upstate New York. But Amy sounds a bit dismayed when she says, “None of my customers have ever asked where the wheat or flour come from. I hate to admit it, but it’s true.”