The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality (4 page)

Read The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality Online

Authors: Richard Heinberg

Tags: #BUS072000

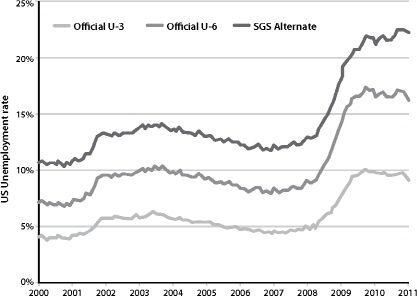

FIGURE 2.

Economic Growth and Unemployment, 2006–2010.

As the US economy contracted from the financial crisis in 2008, economic growth went negative and the unemployment rate shot up. Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

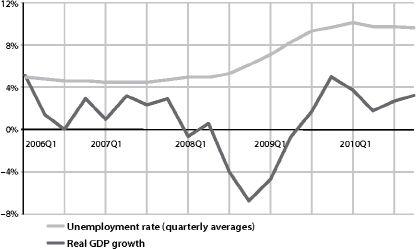

FIGURE 3.

Economic Growth, Stimulus, and Bailouts.

“Bailout and Stimulus” refers to the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. As this graph shows, these federal government expenditures appear to have been the primary source of economic growth since the financial crisis in 2008. What happens when the federal government can no longer bail out the banks and stimulate the economy? Source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis, The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

But Isn’t Growth Normal?

Economies are systems, and as such they follow rules analogous (to a certain extent) to those that govern biological systems. Plants and animals tend to grow quickly when they are young, but then they reach a more or less stable mature size. In organisms, growth rates are largely controlled by genes, but also by availability of food.

In economies, growth seems tied to the availability of resources, chiefly energy (“food” for the industrial system), and credit (“oxygen” for the economy) — as well as to economic planning.

During the past 150 years, expanding access to cheap and abundant fossil fuels enabled rapid economic expansion at an average rate of about three percent per year; economic planners began to take this situation for granted. Financial systems internalized the expectation of growth as a promise of returns on investments.

Most organisms cease growing once they reach adulthood; if curtailment of growth weren’t genetically programmed, plants and animals would outgrow a range of practical constraints: imagine, for example, the survival challenges faced by a two-pound hummingbird. If the analogy holds, then economies must eventually stop growing too. Even if planners (society’s equivalent of regulatory DNA) dictate more growth, at some point increasing amounts of “food” and “oxygen” will cease to be available. It is also possible for wastes to accumulate to the point that the biological systems that underpin economic activity (such as forests, crops, and human bodies) are smothered and poisoned.

But many economists don’t see things this way. That’s probably because current economic theories were formulated during the anomalous historical period of sustained growth that is now ending. Economists are merely generalizing from their experience: they can point to decades of steady growth in the recent past, and they simply project that experience into the future.

10

Moreover, they have theories to explain why modern market economies are immune to the kinds of limits that constrain natural systems: the two main ones have to do with

substitution

and

efficiency

.

If a useful resource becomes scarce, its price will rise, and this creates an incentive for users of the resource to find a substitute. For example, if oil gets expensive enough, energy companies might start making liquid fuels from coal. Or they might develop other energy sources undreamed of today. Many economists theorize that this process of substitution can go on forever. It’s part of the magic of the free market.

Boosting efficiency means doing more with less. In the US, the number of dollars generated in the economy for every unit of energy consumed has increased steadily over recent decades.

11

Part of this increasing efficiency is a result of outsourcing manufacturing to other nations — which must then burn the coal, oil, or natural gas to make our goods. (If we were making our own running shoes and LCD TVs, we’d be burning that fuel domestically.)

12

Economists also point to another, related form of efficiency that has less to do with energy (in a direct way, at least): the process of identifying the cheapest sources of materials, and the places where workers will be most productive or work for the lowest wages. As we increase efficiency, we use less — of energy, resources, labor, or money — to do more. That enables more economic growth.

Finding substitute resources and upping efficiency are undeniably effective adaptive strategies of market economies. Nevertheless, the question remains as to how long these strategies can continue to work in the real world — which is governed less by economic theories than by the laws of physics. In the real world, some things don’t have substitutes, or the substitutes are too expensive, or don’t work as well, or can’t be produced fast enough. And efficiency follows a law of diminishing returns: the first gains in efficiency are usually cheap, but every further incremental gain tends to cost more, until further gains become prohibitively expensive.

In the end, we can’t outsource more than 100 percent of manufacturing, we can’t transport goods with zero energy, and we can’t enlist the efforts of workers and count on their buying our products while paying them nothing. Unlike most economists, most physical scientists recognize that growth within any functioning, bounded system has to stop sometime.

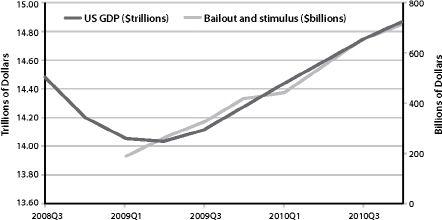

BOX I.2

Cooking the Books on Growth

Are government economic statistics accurate and credible? Not according to consulting economist John Williams of

shadowstats.com

. After a “lengthy process of exploring the history and nature of economic reporting and interviewing key people involved in the process from the early days of government reporting through the present,” Williams began compiling his own data and publishing them on his website. In some cases, as with unemployment statistics, he simply highlights the discrepancy between current definitions and reporting practices and former ones: if unemployment numbers were reported today the way they were in the 1970s, the current figure would be in the range of 16–18 percent rather than the officially reported 9–10 percent (for example, people who have given up looking for jobs are no longer categorized as “unemployed”).

“Shadow stats” for inflation are consistently higher than the government’s reported figures, and GDP growth rates consistently lower.

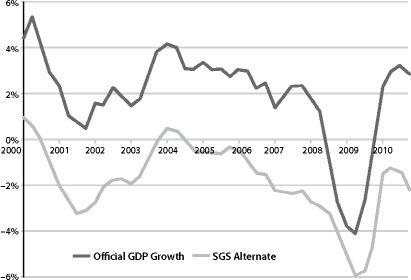

Regarding Figure 4, Williams notes, “The SGS-Alternate GDP reflects the inflation-adjusted, or real, year-to-year GDP change, adjusted for distortions in government inflation usage and methodological changes that have resulted in a built-in upside bias to official reporting.”

All of which raises the question: How much of the economic “recovery” is actually only smoke and mirrors?

The Simple Math of Compounded Growth

In principle, the argument for an eventual end to growth is a slam-dunk. If any quantity grows steadily by a certain fixed percentage per year, this implies that it will double in size every so-many years; the higher the percentage growth rate, the quicker the doubling. A rough method of figuring doubling times is known as the rule of 70: dividing the percentage growth rate into 70 gives the approximate time required for the initial quantity to double. If a quantity is growing at 1 percent per year, it will double in 70 years; at 2 percent per year growth, it will double in 35 years; at 5 percent growth, it will double in only 14 years, and so on. If you want to be more precise, you can use the Y^x button on a scientific calculator, but the rule of 70 works fine for most purposes.

Here’s a real-world example: Over the past two centuries, human population has grown at rates ranging from less than one percent to more than two percent per year. In 1800, world population stood at about one billion; by 1930 it had doubled to two billion. Only 30 years later (in 1960) it had doubled again to four billion; currently we are on track to achieve a third doubling, to eight billion humans, around 2025. No one seriously expects human population to continue growing for centuries into the future. But imagine if it did — at just 1.3 percent per year (its growth rate in the year 2000). By the year 2780 there would be 148 trillion humans on Earth — one person for each square meter of land on the planet’s surface.

It won’t happen, of course.

In nature, growth always slams up against non-negotiable constraints sooner or later. If a species finds that its food source has expanded, its numbers will increase to take advantage of those surplus calories — but then its food source will become depleted as more mouths consume it, and its predators will likewise become more numerous (more tasty meals for them!). Population “blooms” (or periods of rapid growth) are nearly always followed by crashes and die-offs.

13

Here’s another real-world example. In recent years China’s economy has been growing at eight percent or more per year; that means it is more than doubling in size every ten years. Indeed, China now consumes more than twice as much coal as it did a decade ago — the same with iron ore and oil. The nation now has four times as many highways as it did, and almost five times as many cars. How many more doublings can occur before China has used up its key resources — or has simply decided that enough is enough and has stopped growing? The question is hard to answer with a specific number, but it is unlikely to be a large one.

This discussion has very real implications, because the economy is not just an abstract concept; it is what determines whether we live in luxury or poverty, whether we eat or starve. If economic growth ends, everyone will be impacted, and it will take society years to adapt to this new condition. Therefore it is important to know whether that moment is close at hand or distant in time.

FIGURE 4.

US GDP Growth, Official vs. Shadowstats, 2000–2010.

Official GDP data comes from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The SGS Alternate comes from Shadow Government Statistics. Both datasets are adjusted for inflation. Source: Shadow Government Statistics, American Business Analytics and Research LLC,

shadowstats.com