The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality (3 page)

Read The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality Online

Authors: Richard Heinberg

Tags: #BUS072000

•

Financial disruptions

due to the inability of our existing monetary, banking, and investment systems to adjust to both resource scarcity and soaring environmental costs — and their inability (in the context of a shrinking economy) to service the enormous piles of government and private debt that have been generated over the past couple of decades.

Despite the tendency of financial commentators to ignore environmental limits to growth, it is possible to point to literally thousands of events in recent years that illustrate how all three of the above factors are interacting, and are hitting home with ever more force.

Consider just one: the Deepwater Horizon oil catastrophe of 2010 in the US Gulf of Mexico.

The fact that BP was drilling for oil in deep water in the Gulf of Mexico illustrates a global trend: while the world is not in danger of

running out

of oil anytime soon, there is very little new oil to be found in onshore areas where drilling is cheap. Those areas have already been explored and their rich pools of hydrocarbons are being depleted. According to the International Energy Agency, by 2020 almost 40 percent of world oil production will come from offshore. So even though it’s hard, dangerous, and expensive to operate a drilling rig in a mile or two of ocean water, that’s what the oil industry must do if it is to continue supplying its product. That means more expensive oil.

Obviously, the environmental costs of the Deepwater Horizon blowout and spill were ruinous. Neither the US nor the oil industry can afford another accident of that magnitude. So, in 2010 the Obama administration instituted a deepwater drilling moratorium in the Gulf of Mexico while preparing new drilling regulations. Other nations began revising their own deepwater oil exploration guidelines. These will no doubt make future blowout disasters less likely, but they add to the cost of doing business and therefore to the already high cost of oil.

The Deepwater Horizon incident also illustrates to some degree the knock-on effects of depletion and environmental damage upon financial institutions. Insurance companies have been forced to raise premiums on deepwater drilling operations, and impacts to regional fisheries have hit the Gulf Coast economy hard. While economic costs to the Gulf region were partly made up for by payments from BP, those payments forced the company to reorganize and resulted in lower stock values and returns to investors. BP’s financial woes in turn impacted British pension funds that were invested in the company.

This is just one event — admittedly a spectacular one. If it were an isolated problem, the economy could recover and move on. But we are, and will be, seeing a cavalcade of environmental and economic disasters, not obviously related to one another, that will stymie economic growth in more and more ways. These will include but are not limited to:

• Climate change leading to regional droughts, floods, and even famines;

• Shortages of energy, water, and minerals; and

• Waves of bank failures, company bankruptcies, and house foreclosures.

Each will be typically treated as a special case, a problem to be solved so that we can get “back to normal.” But in the final analysis, they are all related, in that they are consequences of a growing human population striving for higher per-capita consumption of limited resources (including non-renewable, climate-altering fossil fuels), all on a finite and fragile planet.

Meanwhile, the unwinding of decades of buildup in debt has created the conditions for a once-in-a-century financial crash — which is unfolding around us, and which on its own has the potential to generate substantial political unrest and human misery.

The result: we are seeing a perfect storm of converging crises that together represent a watershed moment in the history of our species. We are witnesses to, and participants in, the transition from decades of economic growth to decades of economic contraction.

The End of Growth Should Come As No Surprise

The idea that growth will stall out at some point this century is hardly new. In 1972, a book titled

Limits to Growth

made headlines and went on to become the best-selling environmental book of all time.

1

That book, which reported on the first attempts to use computers to model the likely interactions between trends in resources, consumption, and population, was also the first major scientific study to question the assumption that economic growth can and will continue more or less uninterrupted into the foreseeable future.

State of the World

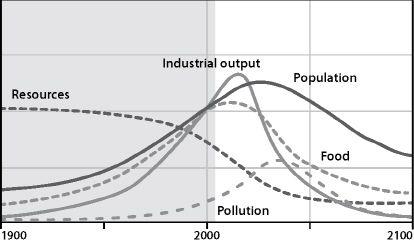

FIGURE 1.

Limits to Growth Scenario.

Source: The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update (2004), p. 169.

The idea was heretical at the time — and still is. The notion that growth

cannot

and

will not

continue beyond a certain point proved profoundly upsetting in some quarters, and soon

Limits to Growth

was prominently “debunked” by pro-growth business interests. In reality, this “debunking” merely amounted to taking a few numbers in the book completely out of context, citing them as “predictions” (which they explicitly were not), and then claiming that these predictions had failed.

2

The ruse was quickly exposed, but rebuttals often don’t gain nearly as much publicity as accusations, and so today millions of people mistakenly believe that the book was long ago discredited. In fact, the original

Limits to Growth

scenarios have held up quite well. (A recent study by Australian Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) concluded, “[Our] analysis shows that 30 years of historical data compares favorably with key features of [the

Limits to Growth

] business-as-usual scenario....”)

3

The authors fed in data for world population growth, consumption trends, and the abundance of various important resources, ran their computer program, and concluded that the end of growth would probably arrive between 2010 and 2050. Industrial output and food production would then fall, leading to a decline in population.

The

Limits to Growth

scenario study has been re-run repeatedly in the years since the original publication, using more sophisticated software and updated input data. The results have been similar each time.

4

Why Is Growth So Important?

During the last couple of centuries, economic growth became virtually the sole index of national well-being. When an economy grew, jobs appeared and investments yielded high returns. When the economy stopped growing temporarily, as it did during the Great Depression, financial bloodletting ensued.

Throughout this period, world population increased — from fewer than two billion humans on planet Earth in 1900 to over seven billion today; we are adding about 70 million new “consumers” each year. That makes further economic growth even more crucial: if the economy stagnates, there will be fewer goods and services

per capita

to go around.

We have relied on economic growth for the “development” of the world’s poorest economies; without growth, we must seriously entertain the possibility that hundreds of millions — perhaps billions — of people will never achieve the consumer lifestyle enjoyed by people in the world’s industrialized nations. From now on, efforts to improve quality of life in these nations will have to focus much more on factors such as cultural expression, political freedoms, and civil rights, and much less on an increase in GDP.

Moreover, we have created monetary and financial systems that

require

growth. As long as the economy is growing, that means more money and credit are available, expectations are high, people buy more goods, businesses take out more loans, and interest on existing loans can be repaid.

5

But if the economy is not growing, new money

isn’t

entering the system, and the interest on existing loans cannot be paid; as a result, defaults snowball, jobs are lost, incomes fall, and consumer spending contracts — which leads businesses to take out fewer loans, causing still less new money to enter the economy. This is a self-reinforcing destructive feedback loop that is very difficult to stop once it gets going.

In other words, the existing market economy has no “stable” or “neutral” setting: there is only growth or contraction. And “contraction” can be just a nicer name for recession or depression — a long period of cascading job losses, foreclosures, defaults, and bankruptcies.

We have become so accustomed to growth that it’s hard to remember that it is actually is a fairly recent phenomenon.

Over the past few millennia, as empires rose and fell, local economies advanced and retreated — while world economic activity overall expanded only slowly, and with periodic reversals. However, with the fossil fuel revolution of the past century and a half, we have seen economic growth at a speed and scale unprecedented in all of human history.

6

We harnessed the energies of coal, oil, and natural gas to build and operate cars, trucks, highways, airports, airplanes, and electric grids — all the essential features of modern industrial society. Through the one-time-only process of extracting and burning hundreds of millions of years’ worth of chemically stored sunlight, we built what appeared (for a brief, shining moment) to be a perpetual-growth machine. We learned to take what was in fact an extraordinary situation for granted. It became

normal

.

But as the era of cheap, abundant fossil fuels comes to an end, our assumptions about continued expansion are being shaken to their core. The end of growth is a very big deal indeed. It means the end of an era, and of our current ways of organizing economies, politics, and daily life.

It is essential that we

recognize and understand the significance of

this historic moment

: if we have in fact reached the end of the era of fossil.fueled economic expansion, then efforts by policy makers to continue pursuing elusive growth really amount to a flight from reality. World leaders, if they are deluded about our actual situation, are likely to delay putting in place the support services that can make life in a non-growing economy tolerable, and they will almost certainly fail to make needed, fundamental changes to monetary, financial, food, and transport systems.

As a result, what could be a painful but endurable process of adaptation could instead become history’s greatest tragedy. We can survive the end of growth, and perhaps thrive beyond it, but only if we recognize it for what it is and act accordingly.

BOX I.1

But Isn’t the US Economy Recovering?

From July 2009 through the end of 2010, the US economy posted GDP gains — i.e., signs of growth. Nominal GDP surpassed pre-recession levels in mid-2010, while inflation-adjusted GDP nearly returned to its pre-recession level.

7

This followed GDP contraction in the months December 2007 through June 2009.

8

But, as we will see in Chapter 6, GDP is a poor gauge of overall economic health. Even if GDP has returned to former levels, the economy of the United States is fundamentally changed: unemployment levels are much higher and tax revenues for state and local governments are severely reduced. Some economists may define this technically as a recovering and growing economy, but it certainly is not a healthy one.

Moreover, much of this apparent growth has come about because of enormous injections of stimulus and bailout money from the Federal government. Subtract those, and the GDP growth of the past year or so almost disappears.

On the basis of historical analysis of previous financial crises, economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff conclude that the economic crisis of 2008 will have

“. . .deep and lasting effects on asset prices, output and employment. Unemployment rises and housing price declines extend out for five and six years, respectively. On the encouraging side, output declines last only two years on average. Even recessions sparked by financial crises do eventually end, albeit almost invariably accompanied by massive increases in government debt.... The global nature of the [current] crisis will make it far more difficult for many countries to grow their way out through higher exports, or to smooth the consumption effects through foreign borrowing. In such circumstances, the recent lull in sovereign defaults is likely to come to an end.”

9

But this analysis considers only the financial aspects of the crisis and ignores the deeper issues of energy, resources, and environment. The “recovery” that began in 2009 occurred in the context of energy prices that had fallen substantially from their peak in mid-2008; but as consumer demand showed tepid signs of revival in late 2010, oil prices lofted upward again. If this “recovery” continues, energy prices will rise even further and contraction will resume.

In short: while the US economy may have posted growth (as technically defined) in 2009–2010, it is operating in a fundamentally different mode than before: it is led to a greater extent than before by government spending (as opposed to consumer activity), and it is hostage to energy prices.