The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality (16 page)

Read The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality Online

Authors: Richard Heinberg

Tags: #BUS072000

For householders facing unaffordable mortgage payments or a punishing level of credit card debt, a jubilee may sound like a splendid idea. But what would that actually mean today, if carried out on a massive scale — when debt has become the very fabric of the economy? Remember: we have created an economic machine that needs debt like a car needs gas.

Realistically, we are unlikely to see a general debt jubilee in coming years (though we’ll reconsider that possibility in more detail in Chapter 6); what we may see instead are defaults and bankruptcies that accomplish essentially the same thing — the destruction of debt. Which, in an economy like ours, effectively means a destruction of wealth and claims upon wealth. Debt would have to be written off in enormous amounts — by the trillions of dollars. Over the short term, government could attempt to stanch this flood of debt-shedding in the household, corporate, and financial sectors by taking on more debt of its own — but eventually it might not be able to keep up, given the inherent limits on government borrowing discussed above. Central banks could also help keep banks’ toxic assets hidden, a strategy the Fed seems in fact to be pursuing, though it is one not likely to succeed indefinitely.

We began with the question, “How close are we to hitting the limits to debt?” The evident answer is: we have already probably hit realistic limits to household debt and corporate debt; the ratio of US total debt-to-GDP is probably near or past the danger mark; and limits to government debt may be within sight, though that conclusion is more controversial.

Stimulus Duds, Bailout Blanks

In response to the financial crisis, governments and central banks have undertaken a series of extraordinary, dramatic measures. In this section we will focus primarily on the US (the bailouts of banks, insurance and car companies, and Government Sponsored Enterprises — i.e., Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac; the stimulus packages of 2008 and 2009; and actions by, and new powers given to the Federal Reserve); later we will also briefly touch upon some actions by governments and central banks in other nations (principally China and the Eurozone).

For the US, actions undertaken by the Federal government and the Federal Reserve bank system have so far resulted in totals of $3 trillion actually spent and $11 trillion committed as guarantees. Some of these actions are discussed below; for a complete tally of the expenditures and commitments, see the online CNN Bailout Tracker.

24

Bailouts

Bailouts directly funded by the US Department of the Treasury were mostly bundled together under the Troubled Assets Relief Program (TARP), signed into law October 3, 2008, which allowed the Treasury to purchase or insure up to $700 billion worth of “troubled assets.” These were defined as residential or commercial mortgages and “any securities, obligations, or other instruments that are based on or related to such mortgages,” issued on or before March 14, 2008. Essentially, TARP allowed the Federal government to purchase illiquid, difficult-to-value assets (primarily CDOs) from banks and other financial institutions in order to prevent a wave of insolvency from sweeping the financial world. The list of companies receiving TARP funds included the largest, wealthiest, and most powerful firms on Wall Street — Citigroup, Bank of America, AIG, JPMorgan Chase, Wells Fargo, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley — as well as GMAC, General Motors, and Chrysler.

The program was controversial, with some calling it “lemon socialism” (privatization of profits and socialization of losses). Critics were especially outraged when it became known that executives in the bailed-out companies were continuing to reward themselves with enormous salaries and bonuses. Some instances of fraud were uncovered, as well as the use of substantial amounts of money by participating companies to lobby against financial reforms.

Nevertheless, some of the initial fears about good money being thrown after bad did not appear to be borne out. Much of the TARP outlay was quickly repaid (for example, as of mid-2010, over $169 billion of the $245 billion invested in US banks had been paid back, including $13.7 billion in dividends, interest and other income). Some of the repayment efforts appeared to be motivated by the desire on the part of companies to get out from under onerous restrictions (including restrictions by the Obama administration on executive pay).

A bailout of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was announced in September 2008 in which the federal government, via the Federal Housing Finance Agency, placed the two firms into conservatorship, dismissed the firms’ chief executive officers and boards of directors, and made the Treasury 79.9 percent owners of each GSE. The authority of the US Treasury to continue paying to stabilize Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac is limited only by statutory constraints to Federal government debt. The Fannie-Freddie bailout law increased the national debt ceiling $800 billion, to a total of $10.7 trillion, in anticipation of the potential need for government mortgage purchases.

The US market for mortgage-backed securities had collapsed from $1.9 trillion in 2006 to just $50 billion in 2008. Thus the upshot of the Freddie-Fannie bailout was that the Federal government became the US mortgage lender of first and last resort.

Altogether, the bailouts succeeded in preventing an immediate meltdown of the national (and potentially the global) financial system. But they did not significantly alter the culture of Wall Street (i.e., the paying of exorbitant bonuses for the acquisition of inappropriate risk via cutthroat competition that ignores long-term sustainability of companies or economies). And they did not relieve the underlying solvency crisis faced by the banks — they merely papered these problems over temporarily, until the remaining bulk of the “troubled” assets are eventually marked to market (listed on banks’ balance sheets at realistic values). Meanwhile, the US government has taken on the burden of guaranteeing most of the nation’s mortgages, in a market in which residential and commercial real estate values may be set to decline further.

Stimulus Packages

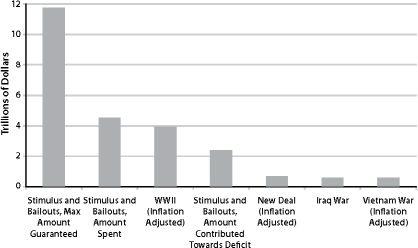

During 2008 and 2009, the US Federal government implemented two stimulus packages, spending a total of nearly $1 trillion.

The first (the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008) consisted of direct tax rebates, mostly distributed at $300 per taxpayer, or $600 per couple filing jointly. The total cost of the bill was projected at $152 billion.

The second, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, or ARRA, was comprised of an enormous array of projects, tax breaks, and programs — everything from $100 million for free school lunch programs to $6 billion for the cleanup of radioactive waste, mostly at nuclear weapons production sites. The total nominal worth of the spending package was $787 billion. A partial list:

• Tax incentives for individuals (e.g., a new payroll tax credit of $400 per worker and $800 per couple in 2009 and 2010). Total: $237 billion.

• Tax incentives for companies (e.g., to extend tax credits for renewable energy production). Total: $51 billion.

• Healthcare (e.g., Medicaid). Total: $155.1 billion.

• Education (primarily, aid to local school districts to prevent layoffs and cutbacks). Total: $100 billion.

• Aid to low-income workers, unemployed, and retirees (including job training). Total: $82.2 billion ($40 billion of this went to provide extended unemployment benefits through Dec. 31, and to increase them).

• Infrastructure Investment. Total: $105.3 billion.

• Transportation. Total: $48.1 billion.

• Water, sewage, environment, and public lands. Total: $18 billion.

In addition to these two programs, Congress also appropriated a total of $3 billion for the temporary Car Allowance Rebate System (CARS) program, known colloquially as “Cash for Clunkers,” which provided cash incentives to US residents to trade in their older gas guzzlers for new, more fuel-efficient vehicles.

The New Deal had cost somewhere between $450 and $500 billion and had increased government’s share of the national economy from 4 percent to 10 percent. ARRA represented a much larger outlay that was spent over a much shorter period, and increased government’s share of the economy from 20 percent to 25 percent.

Given the scope and cost of the two stimulus programs, they were bound to have some effect — though the extent of the effect was debated mostly along political lines. The 2008 stimulus helped increase consumer spending (one study estimated that the stimulus checks increased spending by 3.5 percent).

25

And unemployment undoubtedly rose less in 2009– 2010 than it would have done without ARRA.

Whatever the degree of impact of these spending programs, it appeared to be temporary. For example, while “Cash for Clunkers” helped sell almost 700,000 cars and nudged GM and Chrysler out of bankruptcy, once the program expired US car sales languished at their lowest level in 30 years.

At the end of 2010, President Obama and congressional leaders negotiated a compromise package of extended and new tax cuts that, in total, would reduce potential government revenues by an estimated $858 billion. This was, in effect, a third stimulus package.

Critics of the stimulus packages argued that transitory benefits to the economy had been purchased by raising government debt to frightening levels.

26

Proponents of the packages answered that, had government not acted so boldly, an economic crisis might have turned into complete and utter ruin.

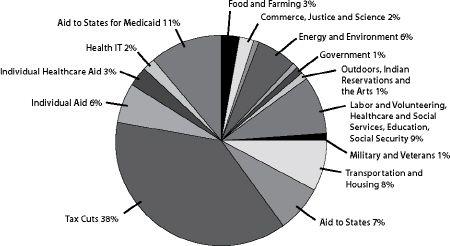

FIGURE 19A.

Stimulus and Bailouts of 2008–2010.

Since 2008, the Federal Government has allocated close to $12 trillion for stimulus and bailout programs. However, all this money has not actually been spent. So far, $4.6 trillion has been spent to stabilize the economy. The contribution of stimulus and bailout spending towards the deficit is still smaller, just over $2 trillion; the reason being, in part, that the actions of the Federal Reserve (bank guarantees, loans, and asset purchases) are not considered a contribution towards the deficit. Also, most of the TARP money has since been repaid.

Source: The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

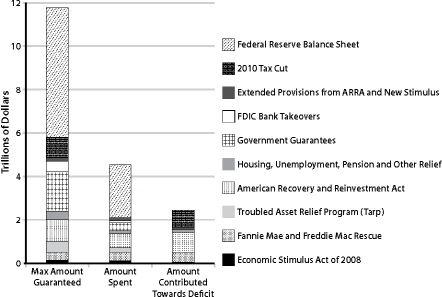

FIGURE 19B.

2008–2010 Stimulus and Bailouts Compared to Past Government

Spending.

The stimulus and bailouts of 2008–2010 dwarf most previous federal expenditures for a single purpose, exceeding even US spending for WWII. Source: The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, Los Angeles Times,

Forbes.com

.