The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality (14 page)

Read The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New Economic Reality Online

Authors: Richard Heinberg

Tags: #BUS072000

Indeed, the housing bubble of the early 2000s had become the oxygen of the US economy — the source of jobs, the foundation for Wall Street’s recovery from the dot-com bust, the bait for foreign capital, and the basis for household wealth accumulation and spending. Its bursting changed everything.

And there is reason to think it has not yet fully deflated: commercial real estate may be waiting to exhale next. Over the next five years, about $1.4 trillion in US commercial real estate loans will reach the end of their terms and require new financing. Commercial property values have fallen more than 40 percent nationally since their 2007 peak, so nearly half the loans are underwater. Vacancy rates are up and rents are down.

The impact of the real estate crisis on banks is profound, and goes far beyond defaults upon outstanding mortgage contracts: systemic dependence on MBSs, CDOs, and derivatives means many of the banks, including the largest, are effectively insolvent and unable to take on more risk (we’ll see why in more detail in the next section).

Demographics do not favor a recovery of the housing market anytime soon. The oldest of the Baby Boomers are 65 and entering retirement. Few have substantial savings; many had hoped to fund their golden years with house equity — and to realize that, they must sell. This will add more houses to an already glutted market, driving prices down even further.

In short, real estate was the main source of growth in the US during the past decade. With the bubble gone, leaving a gaping hole in the economy, where will new jobs and further growth come from? Can the problem be solved with yet another bubble?

BOX 2.2

How to Create a Financial Crisis

In their IMF Working Paper, “Inequality, Leverage and Crises,” Michael Kumhof and Romain Rancière construct a simple model for financial crises with the following narrative: (a) growing inequality produces less money for the middle class and more money for the wealthy; (b) the rich loan much of this money back to the middle class so they can continue to improve their living standards even with stagnant incomes; (c) the financial sector expands to mediate all this; and (d) this eventually results in a credit crisis. Kumhof and Rancière write, in summary:

“This paper has presented stylized facts and a theoretical framework that explore the nexus between increases in the income advantage enjoyed by high income households, higher debt leverage among poor and middle income households, and vulnerability to financial crises. This nexus was prominent prior to both the Great Depression and the recent crisis. In our model it arises as a result of increases in the bargaining power of high income households. The key mechanism, reflected in a rapid growth in the size of the financial sector, is the recycling of part of the additional income gained by high income households back to the rest of the population by way of loans, thereby allowing the latter to sustain consumption levels, at least for a while. But without the prospect of a recovery in the incomes of poor and middle income households over a reasonable time horizon, the inevitable result is that loans keep growing, and therefore so does leverage and the probability of a major crisis that, in the real world, typically also has severe implications for the real economy.”

12

This dynamic is also occurring between rich nations and poor nations.

Limits to Debt

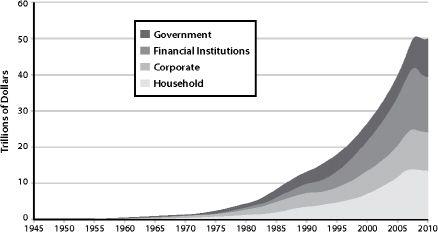

Let’s step back a moment and look at our situation from a slightly different angle. Take a careful look at Figure 18, the total amount of debt extant each year in the US since 1979. The graph breaks the debt down into four categories — household, corporate, financial sector, and government. All have grown very substantially during these past 30+ years, with the largest percentage growth having taken place in the financial sector. Note the shape of the curve: it is not a straight line (which would indicate additive growth); instead, up until 2008, it more closely resembles the J-curve of compounded or exponential growth (as discussed in the Introduction).

Growth that proceeds this way, whether it’s growth in US oil production from 1900 to 1970 or growth in the population of

Entamoeba histo-lytica

in the bloodstream of a patient with amoebic dysentery, always hits hard limits eventually.

With regard to debt, what are those limits likely to be and how close are we to hitting them?

A good place to start the search for an answer would be with an exploration of how we have managed to grow our debt so far. It turns out that, in an economy that’s based on money creation through fractional reserve banking, with ever more loans being taken out to finance ever more consumer purchases and capital projects, it is usually possible to repay earlier debts along with the interest attached to those debts. There is never enough money in the system at any one time to repay

all

outstanding debt with interest; but, as long as total debt (and therefore the money supply as well) is constantly growing, that doesn’t pose a practical problem. The system as a whole does have some of the characteristics of a bubble or a Ponzi scheme, but it also has a certain internal logic and even the potential for (temporary) dynamic stability.

FIGURE 18.

Total US Debt, 1945–2010.

US debt by sector in nominal values (not inflation adjusted). We see the rapid expansion of both household and financial sector debt beginning in 2000, spurred by low interest rates and rising home values. Starting in 2008, household and financial debt contract, while government debt expands. Source: The Federal Reserve, Z.1 Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States.

However, there are practical limits to debt within such a system, and those limits are likely to show up in somewhat different ways for each of the four categories of debt indicated in the graph.

Government Debt

With government debt, problems arise when required interest payments become a substantial fraction of tax revenues. Let’s start with some basics:

•

Government debt

is the total of what the government owes.

• Payment of government debt can obviously be delayed, but controversy exists over how long payment can reasonably be delayed.

• Government debt results, of course, in

interest payments

. Every year federal

revenues

must be used to pay interest on the government debt (which was incurred in the past). There are usually disagreements on whether the interest was incurred for a good purpose, but everyone agrees that it is important to know exactly how much money is owed in interest when planning for the future.

• Both government debt and interest payments can increase. If the government spends more than it takes in during a specific year, a shortfall develops. That shortfall is referred to as the

deficit

. The government handles the deficit by borrowing more money (at interest). Thus the deficit is the shortfall for a specific year, and the government debt is the total of those shortfalls.

• A deficit not only adds to

government debt

(that IOU over there in the corner) but it adds to the

interest

payments (right here, not over there in the corner) that must be made every year. Those interest payments are made with the

tax revenues

that the government collects every year, or with more borrowing.

Currently for the US, the total Federal budget amounts to about $3.5 trillion, of which 12 percent (or $414 billion) goes toward interest payments. But in 2009, tax revenues amounted to only $2.1 trillion; thus interest payments currently consume almost 20 percent, or nearly one-fifth, of tax revenues. For various reasons (including the economic recession, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Bush tax cuts, and various stimulus programs) the Federal government is running a deficit of over a trillion dollars a year currently. That adds to the debt, and therefore to future interest payments. Government debt stands at over $14 trillion now (it has increased by more than 50 percent since 2006).

13

By the time the debt reaches $20 trillion, probably only a few years from now, interest payments may constitute the largest Federal budget outlay category, eclipsing even military expenditures.

14

If Federal revenues haven’t increased by that time, government debt interest payments will be consuming 20 percent of them. Interest already eats up nearly half the government’s income tax receipts, which are estimated at $901 billion for fiscal year 2010.

15

Clearly, once 100 percent of government revenues have to go toward interest payments and all government operations have to be funded with more borrowing — on which still more interest will have to be paid — the system will have arrived at a kind of financial singularity: a black hole of debt, if you will. But in all likelihood we would not have to get to that ultimate impasse before serious problems appear. Many economic commentators suggest that when government has to spend 30 percent of tax receipts on interest payments, the country is in a debt trap from which there is no easy escape. Given current trajectories of government borrowing and interest rates, that 30 percent mark could be hit in just a few years. Even before then, US credit worthiness will take a beating.

However, some argue that limits to government debt (due to snowballing interest payments) need not be a hard constraint — especially for a large nation, like the US, that controls its own currency.

16

The United States government is constitutionally empowered to create money, including creating money to pay the interest on its debts. Or, the government could in effect loan the money to itself via its central bank, which would then rebate interest payments back to the Treasury (this is in fact what the Treasury and Fed are doing with Quantitative Easing 2, discussed below).

17

The most obvious complication that might arise is this: If at some point general confidence that external US government debt (i.e., money owed to private borrowers or other nations) will be repaid with debt of equal “value” were deeply and widely shaken, potential buyers of that debt might decide to keep their money under the metaphorical mattress (using it to buy factories or oilfields instead), even if doing so posed its own set of problems. Then the Fed would become virtually the only available buyer of government debt, which might undermine confidence in the US dollar, possibly igniting a rapid spiral of refusal that would end only when the currency failed. There are plenty of historic examples of currency failures, so this would not be a unique occurrence.

18

Some who come to understand that government deficit spending is unsustainable immediately conclude that the sky is falling and doom is imminent. It is disquieting, after all, to realize for the first time that the world economic system is a kind of Ponzi scheme that is only kept going by the confidence of its participants. But as long as deficit spending doesn’t exceed certain bounds, and as long as the economy resumes growth in the not-too-distant future, then the scheme can be sustained for quite some time. In fact, Ponzi schemes theoretically can continue forever — if the number of potential participants is infinite. The absolute size of government debt is not necessarily a critical factor, as long as future growth will be sufficient so that the proportion of debt relative to revenues remains the same. Even an increase in that proportion is not necessarily cause for alarm, as long as it is only temporary. This, at any rate, is the Keynesian argument. Keynesians would also point out that government debt is only one category of total debt, and that US government debt hasn’t grown proportionally relative to other categories of debt to any alarming degree (until the current recession). Again, as long as growth returns, further borrowing can be justified (up to a point) — especially if the goal is to restart growth.

19

The risks of increasing government debt can be summarized as: (a) rising interest costs, (b) loss of credit-worthiness, and (c) potential currency failure.

Household Debt

The limits to household debt are different, but somewhat analogous: consumers can’t create money the way banks (and some governments) do, and can’t take on more debt if no one will lend to them. Lenders usually require collateral, so higher net worth (often in the form of house equity) translates to greater ability to take on debt; likewise, lenders wish to see evidence of ability to make payments, so a higher salary also translates to a greater ability to take on increased levels of debt.

As we have seen, the actual inflation-adjusted income of American workers has not risen substantially since the 1970s, but home values did rise during the 2000–2006 period, giving many households a higher theoretical net worth. Many homeowners used their soaring house value as collateral for more debt — in many cases, substantially more. At the same time, lenders found ways of easing consumer credit standards and making credit generally more accessible — whether through “no-doc” mortgages or blizzards of credit card offers. The result: household debt increased from less than $2 trillion in 1980 to $13.5 trillion in 2008. This borrowing and spending on the part of US households was not only the major engine of domestic economic expansion during most of the last decade, but a major component of worldwide economic growth as well.