The Empire of Necessity (37 page)

Read The Empire of Necessity Online

Authors: Greg Grandin

The chattel slavery of Africans and African Americans, the historian David Brion Davis writes, had the “great virtue, as an ideal model, of being clear-cut,” compressing and condensing into an exceptionally grotesque, brutal, and visible institution more diffuse forms of human bondage. The horror was so clear-cut, in fact, that it “tended to set slavery off from other species of barbarity and oppression,” including both the mechanisms by which former slaves were “virtually re-enslaved” after the Civil War as well as more subtle “interpersonal knots and invisible webs of ensnarement.” These invisible traps, Davis writes, are “so much a part of the psychopathology of our everyday lives that they have been apparent only to a few poets, novelists, and exceptionally perceptive psychiatrists.”

Herman Melville called them “whale-lines,” and he thought they could hook nations as well as people.

11

1.

“Mordeille! Mordeille!” Citizen Mordeille is the small figure wearing a top hat in the middle of the foregrounded ship, which is about to capture a Swedish slaver. Ange-Joseph-Antoine Roux, 1806.

2.

Did they come to the coast in “small parties” or “caravans”? Were they “Mohamedans or pagans”? Did they have any information about the “great chain of mountains that are reported to extend from Manding to Abysinia”? European slavers often had no idea where their victims came from.

3.

African captives being rowed to a slave ship anchored at Bonny.

4.

Slaves waiting to be sold on the west coast of Africa. Auguste-François Biard, c. 1833.

5.

A rendering of the hold of a Brazilian slave ship, by the Bavarian painter Johann Moritz Rugendas, c. 1827. One enslaved African stretches to raise a water bowl through the hatch while a group of sailors remove a corpse. Rugendas noted in the text accompanying this painting that lack of water was the main cause of both death and revolt among captive Africans.

6.

The peaceful bay of Montevideo full with ships. The “village of blacks” would have been farther to the right. Fernando Brambila, c. 1794.

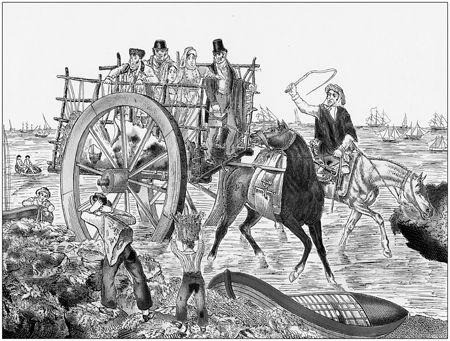

7 and 8.

Buenos Aires later in the nineteenth century, with columns of smoke rising from its saladeros. Before piers were built and the river was dredged, people and cargo had to be disembarked in all-terrain carts, jacked high above the water by large wheels.

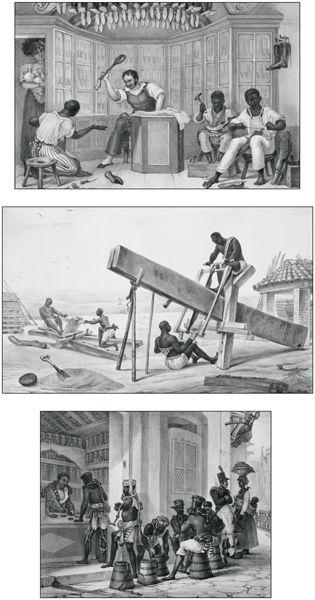

9, 10, and 11.

Slaves in South America were involved in every aspect of economic life, as producers and consumers. The bottom image is of a group of shackled slaves, some of them wearing turbans, forming a queue to buy tobacco in Rio de Janeiro.

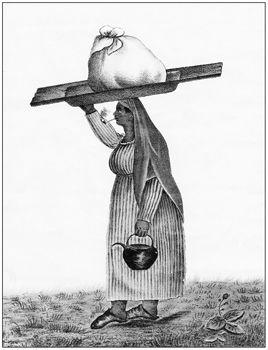

12 and 13.

African and African American itinerant hawkers serviced the growing cities of Buenos Aires and Montevideo. These images of a cake seller and a laundress come from a series of “picturesque” lithographs from the 1830s.