The Elements of Computing Systems: Building a Modern Computer from First Principles (9 page)

Read The Elements of Computing Systems: Building a Modern Computer from First Principles Online

Authors: Noam Nisan,Shimon Schocken

BOOK: The Elements of Computing Systems: Building a Modern Computer from First Principles

8.19Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

2.1 Background

2.2.1 Adders

Binary Numbers

Unlike the decimal system, which is founded on base 10, the binary system is founded on base 2. When we are given a certain binary pattern, say “10011,” and we are told that this pattern is supposed to represent an integer number, the decimal value of this number is computed by convention as follows:

Unlike the decimal system, which is founded on base 10, the binary system is founded on base 2. When we are given a certain binary pattern, say “10011,” and we are told that this pattern is supposed to represent an integer number, the decimal value of this number is computed by convention as follows:

(1)

In general, let

x

=

x

n

x

n

-1

...

x

0

be a string of digits. The value of

x

in base b, denoted (

x

)

b

,

is defined as follows:

The reader can verify that in the case of (10011)

two

, rule (2) reduces to calculation (1).

x

=

x

n

x

n

-1

...

x

0

be a string of digits. The value of

x

in base b, denoted (

x

)

b

,

is defined as follows:

(2)

two

, rule (2) reduces to calculation (1).

The result of calculation (1) happens to be 19. Thus, when we press the keyboard keys labeled ‘1’, ‘9’ and ENTER while running, say, a spreadsheet program, what ends up in some register in the computer’s memory is the binary code 10011. More precisely, if the computer happens to be a 32-bit machine, what gets stored in the register is the bit pattern 00000000000000000000000000010011.

Binary Addition

A pair of binary numbers can be added digit by digit from right to left, according to the same elementary school method used in decimal addition. First, we add the two right-most digits, also called the least significant bits (LSB) of the two binary numbers. Next, we add the resulting carry bit (which is either 0 or 1) to the sum of the next pair of bits up the significance ladder. We continue the process until the two most significant bits (MSB) are added. If the last bit-wise addition generates a carry of 1, we can report overflow; otherwise, the addition completes successfully:

A pair of binary numbers can be added digit by digit from right to left, according to the same elementary school method used in decimal addition. First, we add the two right-most digits, also called the least significant bits (LSB) of the two binary numbers. Next, we add the resulting carry bit (which is either 0 or 1) to the sum of the next pair of bits up the significance ladder. We continue the process until the two most significant bits (MSB) are added. If the last bit-wise addition generates a carry of 1, we can report overflow; otherwise, the addition completes successfully:

We see that computer hardware for binary addition of two

n

-bit numbers can be built from logic gates designed to calculate the sum of three bits (pair of bits plus carry bit). The transfer of the resulting carry bit forward to the addition of the next significant pair of bits can be easily accomplished by proper wiring of the 3-bit adder gates.

n

-bit numbers can be built from logic gates designed to calculate the sum of three bits (pair of bits plus carry bit). The transfer of the resulting carry bit forward to the addition of the next significant pair of bits can be easily accomplished by proper wiring of the 3-bit adder gates.

Signed Binary

Numbers A binary system with n digits can generate a set of 2

n

different bit patterns. If we have to represent signed numbers in binary code, a natural solution is to split this space into two equal subsets. One subset of codes is assigned to represent positive numbers, and the other negative numbers. Ideally, the coding scheme should be chosen in such a way that the introduction of signed numbers would complicate the hardware implementation as little as possible.

Numbers A binary system with n digits can generate a set of 2

n

different bit patterns. If we have to represent signed numbers in binary code, a natural solution is to split this space into two equal subsets. One subset of codes is assigned to represent positive numbers, and the other negative numbers. Ideally, the coding scheme should be chosen in such a way that the introduction of signed numbers would complicate the hardware implementation as little as possible.

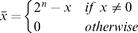

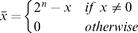

This challenge has led to the development of several coding schemes for representing signed numbers in binary code. The method used today by almost all computers is called the 2’s complement method, also known as radix complement. In a binary system with n digits, the 2’s complement of the number

x

is defined as follows:

x

is defined as follows:

For example, in a 5-bit binary system, the 2’s complement representation of–2 or “minus(00010)

two

” is 2

5

–(00010)

two

= (32)

ten

–(2)

ten

= (30)

ten

= (11110)

two

. To check the calculation, the reader can verify that (00010)

two

+ (11110)

two

= (00000)

two

. Note that in the latter computation, the sum is actually (100000)

two

, but since we are dealing with a 5-bit binary system, the left-most sixth bit is simply ignored. As a rule, when the 2’s complement method is applied to

n

-bit numbers,

x

+ (–

x

) always sums up to 2

n

(i.e., 1 followed by n 0’s)—a property that gives the method its name. Figure 2.1 illustrates a 4-bit binary system with the 2’s complement method.

two

” is 2

5

–(00010)

two

= (32)

ten

–(2)

ten

= (30)

ten

= (11110)

two

. To check the calculation, the reader can verify that (00010)

two

+ (11110)

two

= (00000)

two

. Note that in the latter computation, the sum is actually (100000)

two

, but since we are dealing with a 5-bit binary system, the left-most sixth bit is simply ignored. As a rule, when the 2’s complement method is applied to

n

-bit numbers,

x

+ (–

x

) always sums up to 2

n

(i.e., 1 followed by n 0’s)—a property that gives the method its name. Figure 2.1 illustrates a 4-bit binary system with the 2’s complement method.

An inspection of figure 2.1 suggests that an

n

-bit binary system with 2’s complement representation has the following properties:

n

-bit binary system with 2’s complement representation has the following properties:

Figure 2.1 2’s complement representation of signed numbers in a 4-bit binary system.

■ The system can code a total of 2

n

signed numbers, of which the maximal and minimal numbers are 2

n

–1

–1 and–2

n

–1

, respectively.

n

signed numbers, of which the maximal and minimal numbers are 2

n

–1

–1 and–2

n

–1

, respectively.

■ The codes of all positive numbers begin with a 0.

■ The codes of all negative numbers begin with a 1.

■ To obtain the code of–

x

from the code of x, leave all the trailing (least significant) 0’s and the first least significant 1 intact, then flip all the remaining bits (convert 0’s to 1’s and vice versa). An equivalent shortcut, which is easier to implement in hardware, is to flip all the bits of

x

and add 1 to the result.

x

from the code of x, leave all the trailing (least significant) 0’s and the first least significant 1 intact, then flip all the remaining bits (convert 0’s to 1’s and vice versa). An equivalent shortcut, which is easier to implement in hardware, is to flip all the bits of

x

and add 1 to the result.

A particularly attractive feature of this representation is that addition of any two signed numbers in 2’s complement is exactly the same as addition of positive numbers. Consider, for example, the addition operation (–2) + (–3). Using 2’s complement (in a 4-bit representation), we have to add, in binary, (1110)

two

+ (1101)

two

. Without paying any attention to which numbers (positive or negative) these codes represent, bit-wise addition will yield 1011 (after throwing away the overflow bit). As figure 2.1 shows, this indeed is the 2’s complement representation of -5.

two

+ (1101)

two

. Without paying any attention to which numbers (positive or negative) these codes represent, bit-wise addition will yield 1011 (after throwing away the overflow bit). As figure 2.1 shows, this indeed is the 2’s complement representation of -5.

In short, we see that the 2’s complement method facilitates the addition of any two signed numbers without requiring special hardware beyond that needed for simple bit-wise addition. What about subtraction? Recall that in the 2’s complement method, the arithmetic negation of a signed number

x

, that is, computing–

x

, is achieved by negating all the bits of

x

and adding 1 to the result. Thus subtraction can be easily handled by

x

–

y

=

x

+ (–

y

). Once again, hardware complexity is kept to a minimum.

x

, that is, computing–

x

, is achieved by negating all the bits of

x

and adding 1 to the result. Thus subtraction can be easily handled by

x

–

y

=

x

+ (–

y

). Once again, hardware complexity is kept to a minimum.

The material implications of these theoretical results are significant. Basically, they imply that a single chip, called Arithmetic Logical Unit, can be used to encapsulate all the basic arithmetic and logical operators performed in hardware. We now turn to specify one such ALU, beginning with the specification of an adder chip.

2.2 Specification2.2.1 Adders

We present a hierarchy of three adders, leading to a multi-bit adder chip:

•

Half-adder:

designed to add two bits

•

Full-adder:

designed to add three bits

•

Adder:

designed to add two

n

-bit numbers

Figure 2.2

Half-adder, designed to add 2 bits.

Half-adder, designed to add 2 bits.

We also present a special-purpose adder, called incrementer, designed to add 1 to a given number.

Half-Adder

The first step on our way to adding binary numbers is to be able to add two bits. Let us call the least significant bit of the addition sum, and the most significant bit carry. Figure 2.2 presents a chip, called half-adder, designed to carry out this operation.

The first step on our way to adding binary numbers is to be able to add two bits. Let us call the least significant bit of the addition sum, and the most significant bit carry. Figure 2.2 presents a chip, called half-adder, designed to carry out this operation.

Full-Adder

Now that we know how to add two bits, figure 2.3 presents a

full-adder

chip, designed to add three bits. Like the half-adder case, the full-adder chip produces two outputs: the least significant bit of the addition, and the carry bit.

Now that we know how to add two bits, figure 2.3 presents a

full-adder

chip, designed to add three bits. Like the half-adder case, the full-adder chip produces two outputs: the least significant bit of the addition, and the carry bit.

Other books

Good In Bed by Jennifer Weiner

The Fourth Man by K.O. Dahl

Chloe's Guardian (The Nephilim Redemption Series Book 1) by Cheri Gillard

Midnight Pearls by Debbie Viguié

Nothing Tastes As Good (Cupcake Goddess) by Shéa MacLeod

Relics by Pip Vaughan-Hughes

Deadlocked 5 by Wise, A.R.

Battle Earth VI by Nick S. Thomas

SpecOps (Expeditionary Force Book 2) by Craig Alanson

Plain Promise by Beth Wiseman