The Dragons of Winter (2 page)

Read The Dragons of Winter Online

Authors: James A. Owen

Tags: #Fantasy, #Ages 12 & Up, #Young Adult

Pulling his trench coat tighter against the cold drizzle of the Northampton rain, the Zen Detective sighed and checked his watch. His appointment was late, as usual. He wondered how people who seemed to spend half their lives consulting their watches could ever be late for anything.

Their watches were not like his, which was a Swiss-made, gold-plated chronograph with a pleasant little chime that played Rachmaninoff on the hour and half hour. The watches carried by his clients were less like watches and more like magic devices that could do anything asked of them. He had witnessed the watches being spoken to, as if they operated as a sort of two-way radio. Once, he saw a watch actually project an image of a creature that was all but tangible. And then there seemed to be their most frequent use, which was enabling the bearer to disappear into thin air. All of which shouldn’t have detracted from their ability to keep good time, which was why he wondered how his clients always seemed to be running late.

He was still wondering when the trio of gentlemen appeared behind him, silent as a whisper. “Hello, Aristophanes,” one of them said softly. “Well met.”

“Hades!” the detective exclaimed under his breath, half in shock

and half in relief. “I hate when you do that. And I told you—I’d prefer to be called Steve, if you don’t mind.”

The three men ignored his remark and simply stood there, waiting. It was annoying, the way they played these childish games that seemed to do little more than test his patience. Still, he could ill afford to lose their business. Work in his profession was scarce enough to come by as it was, never mind the fact that his being just a shade lighter than purple, as well as being a Homo sapiens unicorn, always complicated client relations. Even when he wore a trench coat with his collar up and kept the horn on his forehead filed down, just taking a meeting was risky.

Finally the Zen Detective broke the silence. “Well?” he said gruffly. “You wanted to hire me?”

“Yes,” one of the men said. “You know of the Caretakers, correct?”

The detective nodded. “They’re the ones with that book,” he said. “That bloody big atlas, or whatever it is.”

“Indeed,” said the speaker. “You’ve worked for them before, I believe.”

“Just the Frenchman, and only now and again,” came the reply. “Why?”

“They’re going to want to hire you again,” the second man said. “They will want you to find something . . . special. We simply want you to take the job. And to succeed.”

The Zen Detective peered at them. Easy job requests got his hackles up, as well as his radar for a scam. “Is that it? Just take someone else’s job? That’s all you want me to do?”

“There is one other matter we’d like you to deal with, Aristophanes,” the second speaker said. He moved closer to the Zen Detective and spoke softly into the other’s ear. The detective’s eyes grew wide, and against his will his mouth flew open as he uttered a loud, particularly vulgar curse.

“You can’t be serious!” he said in disbelief, stepping back and looking at each of the three men in turn.

As before, none of the men replied, but simply stared impassively back at him.

Each time the three men had hired the Zen Detective, he always had the unnerving impression that they were not the same three men as the time before, even though they appeared to look almost alike.

No,

he thought—

exactly alike.

“There are only eleven personages still walking the Earth who knew, firsthand, those who were driven from Eden,” the first speaker finally said. “Only thirteen more who were alive before the Flood, and fewer than a hundred who have memories of the Inversion that occurred when the Erl-King was born in Bethlehem.

“You live among a very privileged group, Aristophanes,” he continued, and the tone made the statement more a threat than a compliment. “Don’t give anyone cause to lessen that number. You are too valuable to lose.”

The Zen Detective looked up sharply. “Better men, and greater beasts, than you have tried. Killing me is harder than you think, and if you doubt my words, you’re welcome to try.”

“I didn’t say we’d try to kill you,” the speaker replied, “I said you were too valuable to lose. And you should know that death is always preferable to exile.”

Aristophanes held the speaker’s gaze for a long moment, then dropped his eyes and nodded once, then again. “Immortality,” he muttered, more to himself than the others. “It’s a mug’s game.”

“No one lives forever, Aristophanes,” the shadowy figure said as he twirled the dials on his black watch and disappeared. “Not even Caretakers of the

Imaginarium Geographica

.”

P

ART

O

NE

The War of the Caretakers

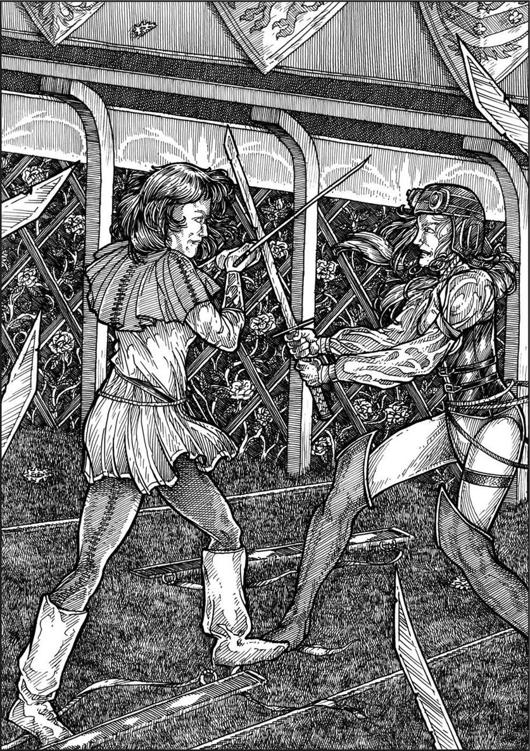

The girls were evenly matched, and fought to a draw . . .

“It’s amazing how productive

dead writers can be,” John commented to Jack as he scanned the shelves in the great library at Tamerlane House. “Some of our colleagues have been more productive after their natural lives than they were beforehand.”

“I would chance a guess that having died brings a lot of focus and clarity to one’s goals,” Jack ventured. “Not that I’m planning on testing that myself any time soon.”

“Take a look at this,” John said, removing a fat volume bound in bright red leather and handing it to his friend. “It’s Hawthorne’s book

Septimius Felton

. I never realized he’d finished it.”

“Finished it, and written a sequel,” a familiar voice answered. The two men turned to see their friend Charles at the door, nodding enthusiastically as he strode into the room, arms outstretched. “He’s having a bit of trouble with the third one, though. Twain and I are helping him work through it.”

John’s self-control was such that he managed to bite his tongue before blurting out what he wanted to say, but Jack was startled enough by Charles’s appearance that he actually dropped the book he was holding.

“Charles!” Jack sputtered. “Your hair . . . it’s—it’s—”

“Purple,” said John.

“Burgundy, actually,” Charles said, preening slightly. “Rose helped me color it. Isn’t it striking?”

“It’s purple,” Jack said, still staring openmouthed as he bent to pick up the book. “Whatever possessed you, Charles? That’s hardly a becoming color for an editor.”

“Possibly,” said Charles, “but it’s also the exact shade of burgundy as Queen Victoria’s throne. I have it on good authority. And besides, I’m not really just an editor anymore, am I? More of a soldier of fortune.”

Jack and John traded disbelieving glances, and the latter asked, “So, ah, who told you that was the color of Victoria’s throne?”

“Geoffrey Chaucer.”

“Mmm,” John hummed. “I see.”

It was traditional, in the old-fraternal-order sort of way, for the Caretakers Emeriti to prank the newer members of their secret society. The problem was that every time John, Jack, and Charles had been present at Tamerlane House, it had been in a crisis situation, and there was no time or inclination for tomfoolery. But now that Charles was a full-time resident, John suspected that the Elder Caretakers—specifically Chaucer—were having a bit of fun.

“Rose helped me do it,” Charles said again as he ran a hand through his full head of hair. “She changes hers on a weekly basis.”

“I’d noticed,” said John, “but she’s still a teenager, and you’re . . .”

“Dead,” Charles said. “But still optimistic about the future.”

Jack laughed, and both he and John shook Charles’s hands. “Fair enough,” John said. “We’re always happy to see you, old fellow.”

The friends had gotten accustomed to having easy access to

Tamerlane House through the use of Shakespeare’s Bridge in the garden at the Kilns. Despite the pain they all still felt over the loss of the Archipelago, it was a comfort to be able to simply cross over and be in the company of the other Caretakers, and thus remind themselves of the value of the work they had done—and the work they still had to do.

Jack was busying himself with preparations for the eventual establishment of a reborn Imperial Cartological Society, including Apprentice and Associate Caretaker programs. It would have to remain an underground project until the Caretakers were truly ready to make it more public, but he and John had already begun actively recruiting the next generations of Caretakers, and were deliberately making it more of a global endeavor than it had been under Verne.

“I see you’ve found Nathaniel’s book,” a voice whined from the doorway. It was Lord Byron, a disgraced Caretaker who was tolerated only reluctantly by the rest of them because of Poe’s insistence that he be included. “It isn’t as good as he thinks it is, you know. It was better when it was unfinished.”

“Say, George,” Jack said, turning to address Byron, whose real name was George Gordon. “I noticed that there’s nothing new in your section of the library. Has inspiration finally failed you?”

“Hardly,” Byron sniffed. “I have more inspiration in my little toe than you have in your whole body. I don’t need to write to demonstrate that—my life is my art.”

“You’re dead, you idiot,” said Sir James Barrie as he entered the room, accompanied by Charles’s apprentice Caretaker, the badger Fred.

“Death is but a new adventure . . . ,” Byron began before the

others’ laughter cut him off. “What?” he said, a blush rising in his cheeks. “What’s funny about that?”

“I’m sorry, George,” Jack said, giving the poet’s shoulder an appreciative squeeze. “All I meant was that I’ve often wondered why someone of your talent never applied it to some grand epic, or an ongoing work of proportions worthy of your ability. That’s all.”

“Oh,” said Byron, who wasn’t certain whether that was actually an apology. “I simply never found the right tale for that kind of treatment.”

“I thought Bert might be with you,” John said, shaking Barrie’s hand. “Does he know we’re here?”

“I couldn’t say,” Barrie answered. “He’s been keeping to himself lately, but I’m sure he’ll be along shortly. The war council was his idea.”

As the Caretakers talked, Fred maintained a respectful distance and kept his opinions to himself. Technically speaking, an apprentice Caretaker had all the standing of a full Caretaker, especially among those at Tamerlane House. But Fred was still a little uncertain about his own position, considering his predecessor was technically deceased. Charles was himself still considered a Caretaker, but a Caretaker Emeritus. He was, like Verne and Kipling, a

tulpa

—a near-immortal, youthful, new body housing an old soul. And unlike the majority of the other Caretakers, who were portraits in Tamerlane, and who could leave the frames for only one week, he could go almost anywhere—as long as it wasn’t somewhere he’d been known when he was alive.

To the animals, dead was dead, and while they tolerated the portraits, none of them—especially the badgers—could quite accept the tulpas. It was something about their smell, Fred once

said to Jack—there was none. Tulpas gave off no odor at all. And to an animal, who determines friend or enemy, truth or lies, based on smell—that made the whole idea completely suspect.

Still, he was sworn to serve the Caretakers, as were his father and grandfather before him, and of them all, Charles had the strongest bond to the badgers. So Fred was cheerfully stoic. Mostly.

“You could do as John is doing,” Jack continued, “and base a great work on stories of the Archipelago.”