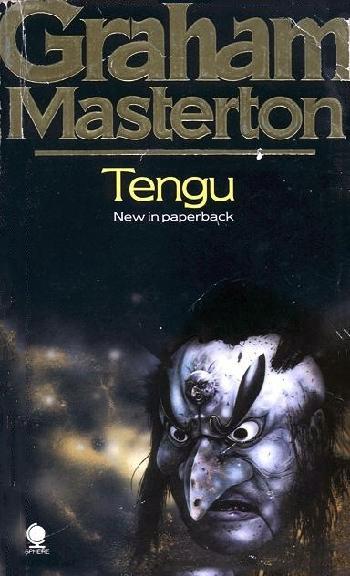

Tengu

Tengu

By

Graham

Masterton

TENGU

– Winner of the Silver Medal of the West Coast of Books

Nancy spoke: “The most evil of all the seven Black Kami is called the

Tengu. Even the most experienced adepts at the Shinto shrine are warned opening

themselves up to the Tengu. It is said that the leader of the shrine had once

done so, and had almost been driven mad.”

“Nancy, please...” Gerard interrupted.

“No. You must listen to me. The characteristics the Tengu gave to those

he possessed included invincible physical strength, the mad strength of the

berserk, the ability to stand up to ferocious attack from any kind of weapon.

Also, if the person he was possessing was chopped into the tiniest pieces, the

pieces would regenerate and grow again into demons even more hideous than the

original...”

“Nancy!” Gerard shouted.

“No!” she hissed. “You have to listen because it’s true! They’ve done

it! They’ve brought it here, the Tengu, the real Tengu demon!

The devil of remorseless destruction!”

STRICTLY

CONFIDENTIAL

TEG/232/Ref

:18a

FROM: THE SECRETARY OF

THE NAVY

TO: SENATOR D. R.

NUSSBAUM

REFERENCE: USS Value

October 17,

Naval

records show indisputably

that the radio monitoring vessel USS Value was at Pearl Harbor on July 2, 1945,

undergoing routine equipment repairs. There can be no basis whatever for your

suggestion that the vessel was anchored at that time

off

the coast of Japan. Nor can there be any substance in your claim that the USS

Value was connected with what you call the “Appomattox Situation.” The Navy has

no record of any file of that title or description.

EXCERPT FROM THE RECORD OF THE CONGRESSIONAL

INQUIRY INTO INTELLIGENCE PROCEDURES, MARCH, 1961.

SEN. NEILSEN (N.J.): Did you at any time prior to this sortie

appreciate that you might have to sacrifice the lives of all but one of your

fellow operatives in order to achieve a comparatively minor intelligence coup?

LT. COL. KASTNER: Yes, sir. I was conscious of the risks. I might add

that my fellow operatives were, too. We were trained.

SEN. NEILSEN: Do you now believe that what you achieved was worth the

loss of all those lives, and worth the political risks which Senator Goldfarb

has already outlined?

LT. COL. KASTNER: There was a possibility that it might have been, sir.

I admit the net result was a disappointment.

SEN. NEILSEN: A disappointment?

LT.

col

. KASTNER: Not all such sorties are

disappointments, sir. Appomattox was a good example.

SEN. NEILSEN: Appomattox? What was Appomattox?

LT. COL. KASTNER: I have just been given instructions that I am not to

respond to that question, sir. It is outside the area of my competence.

SEN. NEILSEN: I think this inquiry deserves some kind of explanation of

your remarks, Colonel.

LT. COL. KASTNER: I’m sorry, sir. I have been advised that any kind of

response would be a violation of national security.

SEN. NEILSEN: Very well, Colonel. But I intend to take this matter

further.

LT. COL. KASTNER: That is your privilege, sir.

MESSAGE

RECEIVED FROM APPOMATTOX ONE, JULY 11, 1945

“We’ve located it, sir. No question about it. We’ve taken sixteen radio

bearings and we have it right on the button.”

“In that case (inaudible) immediately. I repeat, immediately. You will

be picked up at 2125 hours on the 15th on the beach at (inaudible)”

CHAPTER ONE

W

hen Sherry Cantor’s alarm clock woke her at 7:27 on the morning of

August 9 she had twenty-three minutes to live.

That was the

most overwhelming fact of her morning. Yet it was the only fact she didn’t

know.

She knew that

her twenty-second birthday was only three days away. She knew that in two weeks

she was supposed to drive down to San Diego and spend a week with her brother

Manny and his wife Ruth. She knew that she had a date to meet her good-looking

new lawyer, Bert Dentz, in thirteen hours and thirty-three minutes for dinner

at the Palm Restaurant on Santa Monica Boulevard.

She knew that

her savings account at Security Pacific contained $127,053.62, and she knew

that last Wednesday’s Variety had dubbed her “most promising young video star

of 1983.”

But knowing all that was not enough.

Knowing all that could

not possibly save her from what was going to happen in twenty-three minutes’

time.

After the alarm

had woken her up, she lay on her emerald-green satin sheets in her small white

California-rococo bedroom, under the framed black-and-white print of yuccas at

Santa Barbara.

She thought

about the dream she had just been dreaming. It had been vivid, almost realer

than real, as only early-morning dreams can be. She had imagined herself

jumping rope in the front yard of the old white house in Bloomington, Indiana.

She had 14 imagined the leaves falling from the trees like flakes of rust. She

had imagined her mother coming to the door, and waving her to come in for

cookies and milk....

Sherry thought

about her dream, and then let it warmly melt away. Bloomington, Indiana, was

five years ago, and a lifetime away. She stretched on the twisted sheets.

She was a tall,

striking girl with rich chestnut hair and a face that was uncompromisingly

European. Her eyes were wide, and almost amber. She was wide-shouldered,

big-breasted, and narrow-hipped. She slept naked, except for a small pair of

blue satin panties, and her skin was soft and brown against the shiny sheets.

There was a

faded photograph on the sideboard in Bloomington of Sherry’s mother in a

transit camp in Munchen Gladbach, Germany, in 1945. Except for the puff-sleeved

dress and the headscarf, it could have been Sherry.

At 7:31, with

only nineteen minutes left, Sherry sat up in bed and ran her hands through her

tousled hair. On the bleached calico window blind, the first nodding patterns

of sunlight shone through the fan palms in her garden, and made a shadow-play.

Somewhere

outside, a radio was giving the morning traffic report. It was bad everywhere.

Sherry climbed

out of bed, stood up, stretched, and stifled a yawn. Then she padded out of the

bedroom and into her kitchenette. She opened the mock Oregon-oak cupboard and

took down a can of Folger’s coffee. As she reached for her percolator, a triangle

of sunlight lit her hair, and then her shoulder, and then her right breast. The

nipple was pale and soft.

While the

coffee perked. Sherry poured herself an orange-juice and stood in the

kitchenette drinking it. She felt hungry. Last night, she’d shared a bottle of

tequila with Dan Mayhew, the curly-haired actor who played her unhappily

married cousin in Our Family Jones, and hangovers always made her feel hungry.

She opened the

fridge again. There were two Thomas’s muffins left. She wondered how guilty she

would feel if she toasted one.

It was 7:37.

She decided against the muffin. Dan May-hew hadn’t even been worth getting a

hangover over, and so he certainly wasn’t worth putting on weight over. Last

week she’d seen him sitting in the studio commissary with a boy whose pale

lemon ballet shoes and surfer’s knobs hadn’t exactly reassured her about Dan’s

essential virility.

It was 7:39-

There were eleven minutes of life left. Sherry left the kitchenette as the

coffee began to perk, and walked into her small bathroom. There were T-shirts

and panties hanging to dry on a line over the tub. She looked at herself in the

mirror, pouted at

herself

, and pulled down her eyelids

to make sure her eyes weren’t too bloodshot. Lionel–Lionel Schultz, the

director of Our Family Jones–always went crazy if anyone arrived on the floor

with reddened eyes.

‘‘What do you

think we’re shooting here?” he invariably screamed.

“A

fucking Dracula picture?”

Lionel Schultz

wasn’t a gentle man. He wasn’t much of a gentleman, either. But he had a

perverse genius for soap opera, and for provoking believable performances out

of inexperienced actors.

It was Lionel

Schultz who had shown Sherry how to develop the dumb, busty part of Lindsay

Jones into a character of sweet and quirky sympathy. And he hadn’t touched her

once.

Sherry finished

her orange juice and set her glass down on the basin, next to her cake of

herbal soap. She stepped out of her panties, and sat on the toilet. She could

hear the birds chittering in the garden, and the distant murmur of the

freeways. She closed her eyes, and tried to think what she felt like wearing

today.

It was 7:42.

She flushed the toilet, washed her face, and walked back into the kitchenette

naked.

The coffee was

popping and jumping. She picked up the folded-back script that lay on the

counter, next to the Popeye cookie jar, and flicked through two or three pages.

Tengu LINDSAY (sobbing): Is that really what you think of me?

After all those days and nights together?

After all those

things you said?

MARK: Honey,

you don’t understand. I had to tell Carla we were finished. I didn’t have any

other choice.

Riboyne Skel O’/em, thought Sherry.

If anyope had shown me

this script before I signed up for Our Family Jones, I wouldn’t have thought it

was worth turning up at the studio. I would have stayed as a waitress at

Butterfield’s, fetching and carrying white wine and cottage cheese salads for

pretentious British tax exiles in tinted glasses, and been glad of the work.

Who would have guessed that some treacly saga about some even more treacly

family would have gotten off the ground for a pilot and two episodes, let alone

for two series?

Even more

amazing, who would have thought that a Jewish girl from Bloomington, Indiana,

would have been picked out of hundreds of would-be starlets for one of the most

noticeable roles in the whole drama?

There wasn’t

any question that Our Family Jones had cost Sherry the love of her live-in

boyfriend, Mack Holt. Mack was lean and moody, with curly blond hair and a

broken nose, and he could swim and ride and fence and dance like Fred Astaire.

They had met one evening on the plaza outside of the Security Pacific Bank at

Century City, when she had just opened her savings account with $10 her mother

had sent her. The shadows of the dying day had been very Bauhaus, and he had

crossed the plaza at that trotting pace athletes use when they’re just on the

point of breaking into a run. She had been putting away her bankbook; dropped

her purse; and he had picked it up for her in one fell swoop. After such a

meeting, he should have known she would make it in soap opera.

Sherry and Mack

had lived for seven months on the second floor of a brown crumbling hacienda

off Franklin Avenue, in Hollywood. They had shared their three-room apartment

with a lumpy divan, two fraying basketwork chairs,

three

peeling posters for the Grateful Dead, and a dyspeptic gas stove. They had

talked, played records, made love, smoked Mexican grass, argued, gone off to

work, brushed their teeth, and finally arrived at the moment when Lionel had

called to say Sherry was fabulous, and just had to come down to the studio

right away, and Mack, far more talented, but still parking cars for a living,

had refused to kiss her and wish her luck.

From then on,

it had been nothing but sulks, arguments, and eventually, packed suitcases.

Sherry had lived for a while with a plain but friendly girl she knew from

Butterfield’s, and then taken out a mortgage on this small secluded bungalow at

the top of a steeply graded dead end called Orchid Place. She enjoyed the

luxury of living alone, with her own small garden, her own wrought-iron fence,

her own living room, her own perfect peace. She began to think about who she

was, and what she wanted out of her life, and all of her friends said she was

much nicer since she’d left Mack, and much more relaxed.

To ease one of

the more pressing demands of being single, Sherry had bought, through the mail,

a pink vibrator. Most of the time it stayed in her bedside cupboard, next to

her Oil of Olay and her Piz Buin sun oil, but occasionally there were nights

when fantasies crowded her mind, and the Los Angeles heat almost stifled her,

and she used it just to keep herself sane.