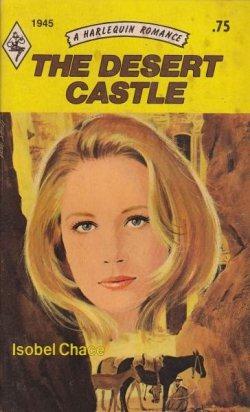

The Desert Castle

Authors: Isobel Chace

T

HE DESERT CASTLE

Isobel Chace

When her mother, rather highhandedly, arranged for her to go out to work for Gregory Randall in Amman, Marion Shirley was uncertain about her feelings.

A

lthough that part of the world was bound to be fascinating, perhaps Gregory himself might be too fascinating for her peace of mind.

‘

It seems no work of Man

’

s creative hand,

By labor wrought as wavering fancy planned;

But from the rock as if by magic grown,

Eternal, silent, beautiful, alone!

Not virgin-white like that old Doric shrine.

Where erst Athena held her rites divine;

Not saintly-grey, like many a minster fane,

That crowns the hill and consecrates the plane;

But rose-red as if the blush of dawn

That first beheld them were not yet withdrawn;

The hues of youth upon a brow of woe,

Which man deemed old two thousand years ago. Match me such a marvel save in Eastern clime,

A rose-red city half as old as Time.

’

From Dean Burgon

’

s Newdigate Prize Poem

‘

Petra

’

CHAPTER

I

The man had no right to be there. Marion Shirley watched him idly from beneath her eyelashes, wondering why he should have gate

-

crashed her class. It was practically the end of term, so it was unlikely that he had enrolled as a student. Besides, he hadn

’

t shown the slightest interest in anything she had said all evening. He had just sat there, making her nerves tingle and distracting her attention from the lesson in hand. It was a good thing she knew tonight

’

s subject backwards, she reflected grimly, or she might have come to a shuddering stop long since under the weight of that lazy stare with which he had favoured her whenever he had not been tapping his fingers on the desk in time to some imaginary tune or, worse still, had gone off into a daydream with an inexpressibly bored look written large on his face.

‘

So we see,

’

she said,

‘

wall paintings are far from always being true frescoes, which is a very specialised technique, where the paint is laid on

damp

plaster, so that it penetrates it and marries into one substance with it. In many instances Byzantine wall paintings were executed in glue or a tempera medium, laid upon hard plaster, in much the same way as they were put on the gesso background of a panel. Over the centuries, the plaster sets to a rock-like hardness. The nature of the plaster varies from district to district, of course, but when making up your mind what was painted where, the stylistic evidence is far more important than the technical.

’

She drew a deep breath, glad that the evening was coming to an end.

‘

Any questions?

’

she snapped out

The man tipped his chair forward and Marion had a sudden, nervous fear that he was about to ask her something that she wouldn

’

t know the answer to. It would be just like

him

to show her up before such

a

disparate class that she was already finding hard to handle.

B

ut the question never came.

‘

Miss Shirley, I asked you if there were any examples of the true fresco in Rome? I

’

m going there for my holidays later this year.

’

Marion turned her attention to the questioner with a burning sense of relief.

‘

Some of the best examples are there,

’

she answered.

‘

Many true frescoes survive in the catacombs and the early churches in Rome.

’

She waited to see if there were any more questions, standing quietly beside the tall desk she had been given on which to prop up her notes. She had learned early in her career to let the interest of the class come to her rather than try to impose her own interests in the subject on them. When she had first been asked to teach the History of Art to an evening class at the local adult education centre, she had been amused to discover that the problems of discipline in a class there were no different from the school where she taught. It didn

’

t matter at all that the students had not only chosen to come along, but had paid to do so, there was always someone intent on breaking up the concentration of others, and the same few who couldn

’

t resist challenging her right to control the class. So far she had always won these battles by exhibiting the quiet good manners that had brought her the support of the majority and had swung the prevailing opinion of the class into being

on

her side, sometimes with a fierce protectiveness that could be equally difficult to control.

If only she had been taller, but even the highest heels couldn

’

t make her more than five feet, two inches. Then she was impossibly pretty, with a fine pair of laughing eyes and an infectious smile that, coupled with a tip

-

tilted nose and a mobility of expression, was of no help to her in front of the blackboard. Try as she would to discipline herself into presenting a sober

mien

to the world, the laughter would peep out to undo all her good work and it would be her leading the gust of laughter as it swept through her class. That she was well liked, she knew, but that she was respected as a fully qualified teacher ought to be respected, she doubted. Her students treated her as one of themselves and

that

had caused her nothing but trouble in the teachers

’

common room where these things mattered almost as much as the academic achievements of the girls concerned.

The smile burst out now.

‘

That

’

s all, then, for tonight,

’

she said.

She hadn

’

t meant to, but she found herself seeking out the place where the strange man had been sitting, to see if he were leaving with the rest. But, on the contrary, he was still lolling at his ease on the hard wooden chair that looked as if it might collapse under him at any moment

.

Her eyes met his, and the thought of him coming to grief there and then brought the laughter to her throat and her lips trembled with the effort of suppressing her amusement.

He stood up and came towards her with the easy movements of a man who was used to walking, and long distances at that. He put a hand on her desk and looked down at her in silence. His eyes, which she had thought were almost black from the other side of the room, were actually a deep navy-blue, she noticed. They

w

ere fringed with long, black eyelashes that matched his eyebrows and his short, curling hair.

His

face was dark as though he lived in the sun, which he probably had, for he had a network of little lines round his eyes which come from looking into the distance under a hot sun. His mouth was straight and disapproving, which made her feel uncomfortable, for the only thing in vision for him to disapprove of was herself.

‘

There

’

s no need to offer to pay for a single lecture,

’

she volunteered, unable to bear the silence between them any longer.

‘

If I don

’

t mark you down as having been present, I don

’

t suppose anyone will notice that

you wandered in by mistake—

’

‘

No mistake, Miss Shirley. I came to see what I thought of

y

ou.

’

W

hat he did think was not much, Marion thought wryly, and wondered why the knowledge hurt

.

She didn

’

t like him much either, come to that!

‘

You have the advantage of me, Mr

.

—

?

’

‘

Gregory Randall,

’

he supplied. He said it as though he were expecting it to mean something to her, but she didn

’

t think she had ever heard the name before.

‘

Well, Mr

.

Randall, class is out as you can see and I

’

m in a hurry to get home.

’

‘

I shan

’

t keep you, Miss Shirley. All I want to know is if you really know what you

’

re talking about when it comes to frescoes and the like. Do you

?

’

‘

Yes,

’

said Marion.

‘

Good enough.

’

The disapproving mouth relaxed into a faint smile.

‘

That

’

s all, Miss Shirley. You can go home now if you like.

’

S

he was about to tell him that he had no means of preventing her from doing exactly as she liked when she caught right of the twinkle in the back of his eyes, and realised that, in his own way, the man was baiting her, no doubt hoping that she would fly out at

hi

m. But why? Was she exaggerating his motives because of the impact he had had on her? He had not, after all, asked any question in front of the class and she had been quite sure that he had been going to.

‘

Thank you,

’

she said. She lifted an ey

eb

row to show her displeasure, but her effect was ruined by the dimple that came and went in her cheek. He was impossible by any standards, she thought, and yet there was something funny about the casual way he dismissed her from her own classroom.

‘

Did you enjoy the lecture

?

’

she asked him.

‘

Parts of it

.

Parts of it I suspected you had mugged up for the occasion, hoping to sound convincing. But you were quite interesting when you were talking about

preserving these wall-paintings, and restoring them where neces

s

ary in village churches and so on.

’

‘

Byzantine art is my particular interest,

’

she told him in frozen tones.

The disapproving mouth relaxed still further into an almost genuine smile.

‘

Oh, quite. Have you done any restoration work yourself

?

’

‘

A little. When my father was alive

—

’

She broke off, a little dismayed that she had been about to tell this unlikeable man all about herself when nobody could have said he had offered her the least encouragement to confide anything but the most ordinary courtesies and those as briefly as possible.

‘

It doesn

’

t matter,

’

she ended.

H

e showed no signs of having noticed her discomfiture.

‘

Know anything about Isl

a

mic art

?

’

he asked her.

She shook her head.

‘

Nothing at all

?

’

She went on shaking her head.

‘

That

’

s one of the bits I hope to mug up—if I touch on it at all.

’