The Delaware Canal (7 page)

Read The Delaware Canal Online

Authors: Marie Murphy Duess

The canal was built with picks, shovels and wheelbarrows predominantly by Irish immigrants and local farmers. It required constant maintenance, which was usually conducted in winter months.

Courtesy of Pennsylvania Canal Society Collection, National Canal Museum, Easton, PA

.

Desperate, the state turned to Josiah White in 1831 and requested that he take over the reconstruction of the canal. The longer it took to complete the Delaware, the more money the LC&N lost, so although he was still mourning the death of his son, White agreed to come out of semiretirement and act as chief engineer.

32

He went to work immediately. In a letter he wrote to John Carey Jr., the superintendent of the Upper Division of the Delaware Canal, he left no doubt about the speed with which he wanted to complete the major repairs that were needed.

I have just received a letter from the Commissioners directing us to make any and all repairs in situations as breaks and leaks, without waiting for specific orders, and with all possible dispatch. As Rocky Falls is the heaviest job in thy section, I particularly wish thee to proceed there with a strong force and get it to hold water

.

33

And in another letter to the Pennsylvania Board of Canal Commissioners, it is clear that he is disgusted by the way the canal was built in the first place.

I have advised the Board, and wish to proceed with certain changes in the water wheels and fixtures for supply of the canal with water below New Hope. Please inform me by early mail whether I am to direct the work to be executed according to the earlier design or whether I am to have the liberty to make such modifications as I may deem best for the purpose intendedâ¦All my experience has gone to prove the impolicy of multiplying machinery when it is not absolutely necessary

.

34

Although there is no mention of it in any of his letters, White must have been infuriated by the fact that had the state allowed him to build the canal when he requested, it would have been completed earlier and correctly. He spent time and energy repairing the canal, addressing the inconsistencies in the locks and aqueducts and trying to fire the men who were not doing their jobs effectively.

By 1832, under the direction of Josiah White, the Delaware Division Canal was repaired properly and was open for use. It was one of the first sections of the state public works to be completed and, in the long run, perhaps one of the best built. The

Easton Whig

reported in November 1833, “The Delaware Canal is in the full tide of successful experiment and the Lehigh Canal is stout and strong.”

35

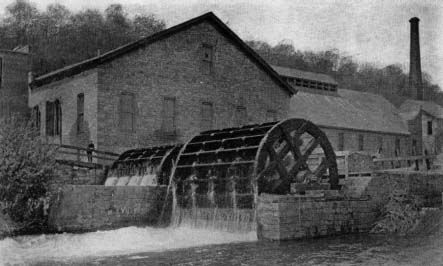

The work Josiah supervised corrected the leakage problem, and the Lehigh was feeding the upper canal properly, but the engineers building the waterway found it necessary to introduce other feeders of water into the canal for the lower level. One of the most industrious and unique was the use of a lifting wheel located at the Union Paper Mills, just south of New Hope, which raised water from a wing dam into the canal. It was built by Lewis S. Coryell and, except for one overhaul in 1880, this water wheel continued to feed the canal without trouble throughout the life of the canal. There were essentially two wheels. The outside wheel was built with paddles that were turned by the flow of water. This controlled the inside wheel, which caught the water in trough-like buckets and emptied into a sluiceway under the mill and into the canal on the other side. The canal was now fully watered.

There were about twenty creeks that flowed directly into the Delaware Canal channel, but they couldn't be counted on to contribute water to the canal. They did, however, deposit large amounts of silt into the channel during spring thaws and heavy storms, creating more work for the maintenance crews who used shovels and wheelbarrows to remove it. Maintenance on the canal was constant, with quick fixes taking place in the summer months and larger problems solved during the winter months.

A water wheel built at the Union Mills just outside of New Hope helped to water the lower end of the Delaware Canal. The mills have been turned into upscale condominiums with beautiful views of the Delaware River.

Courtesy of the Historic Langhorne Association

.

Tolls were collected at the tide lock in Bristol and again in New Hope. Industrial buildings and mills were built along the edge of the canal, as seen in the background.

Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Canal Society Collection, National Canal Museum, Easton, PA

.

At its completion, the Delaware Division Canal was sixty feet long, forty feet wide and seven feet deep. The entire system cost $1,400,000 to build, with additional funds expended in maintaining the canal. There were constant repairs due to leaks, floods and freshets. It was initially believed that the Pennsylvania state canals could be built on borrowed money, and once in operation the loans would be paid off and there would be a surplus paid into the treasury. But when it was completed and a crowd of coal-loaded boats could be seen floating up and down the waterways, the prosperity residents expected wasn't forthcoming. They were exceptionally outraged when taxes were raised to pay the debt.

The revenue from tolls barely exceeded operating expenses. As a result, the state-owned canals were sold to private concerns. In 1866, a ninety-nine-year lease agreement was made between the Delaware Division Canal Company and the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company.

Chapter 4

Locks and Their Keepers

Locks, Aqueducts and Waste Weirs

Locks were crucial to canal operation. They kept the canal water at an even level to allow boats to travel both upstream and downstream no matter the elevation and with no damage to the cargo or the boat. Along the length of the Delaware Canal, there was a gradual drop of 164 feet that necessitated twenty-four locks along the canal.

Built like boxes, locks were set into the canal with gates at either end. The locks built on the Delaware Division were eleven feet wide and ninety-five feet in length. Although initially designed to be built of wood, the Board of Canal Commissioners ultimately were convinced that there was enough stone in the region to build the locks with stone, and the additional costs would be made up in the lack of maintenance later on. A “doghouse” beside the lock contained the mechanisms that would control the opening and closing of the gates as the boats approached and left the locks. A wicket gate was located at the downstream end of the lock, and the fall gatesâor drop gatesâwere upstream where the water pressure was constant. When a boat entered the lock, the gates were shut behind it. Then a valve opened and allowed water to flow into the chamber. The boat rose with the water (or fell, depending upon which way it was moving on the canal) and once the water level matched the level in the next section of the lock and was at a proper depth for the draft of the boat, the gate opened and the captain motioned to the mule driver to begin pulling the boat through so it could continue on to the next section of the canal.

Both company-owned boats and privately owned boats were weighed empty at the start of each season. Then, at the beginning of every journey on the canal, once they were loaded with coal in Mauch Chunk, they would be led into a weigh lock. When a boat was secured inside the weigh lock, the water would lower until the boat rested on the cradle of a large scale. The weighing gear was located inside a building next to the lock where the tender would make notations of its weight in a log beside the LC&N number or name of the boat. He would then hand the boat captain a slip with that informationâthe weight of the load, the time and the charges.

Gates at Lock 20 in Kitnersville.

Courtesy of Historic Langhorne Association

.

Canalboats could carry up to one hundred tons of coal, and each captain of a company boat was allowed two hundred pounds extra per trip for his own use to sell, trade for food or goods along the canal trip or save for the winter.

There were several types of locks along the canal. Some kept the boats moving down to Bristol and others changed the boats' direction across the Delaware River to the Delaware and Raritan Canal. Some of the locks along the Delaware Canal were large enough for two boats to enter at the same time; these were preferred by the boatmen, as they saved time.

When boats were headed to New Jersey to continue their trip on the Raritan Canal, they crossed the Delaware at Lock Number 9 in New Hope. The lock tender would raise a red flag so the New Jersey tenders would know that a boat was ready to cross. The boat would enter what was called a feeder lock to await the crossing. Here, the weight of the boat was measured with the use of a rod that estimated the draft of the boat in the water, and again that data was entered into a log.

Most of the locks on the Delaware Division Canal were built of stone. This lock in New Hope, which is now empty, shows the stone from local quarries that was used in construction.

Author's collection

.

Lock 11 in New Hope as it looks today. Until flooding in the fall and winter of 2007, the canal and locks were fully watered and operational up to Centre Bridge. Repairs are expected to be complete in late 2008.

Author's collection

.