The Delaware Canal (6 page)

Read The Delaware Canal Online

Authors: Marie Murphy Duess

On the day of the hangings, miners and their families gathered at the scaffold and stood in complete silence to show their support of the convicted men. Security was very high for these executions. The wife of one of the men who was to be hanged arrived just after the gates had closed, and despite the fact that she collapsed in sobs, begging to be allowed in, the guards would not allow it.

No one knows for certain which of these men were truly guilty and which were “guilty by association.” Chances are good that both are true.

One of the men hanged in Mauch Chunk that day was Alexander Campbell, a hotel owner and liquor distributor. He avowed his innocence throughout his trial. Campbell left his handprint on the wall of cell number seventeen in Mauch Chunk jail as he was being led to the gallows. He said that the handprint would remain forever as “proof of his words. That mark of mine will never be wiped out. It will remain forever to shame the county for hanging an innocent man.” After 130 years, the handprint still remains on the wall of the cell. According to several accounts, the wall has been painted over numerous times, yet the handprint reappears. To dispel the myth once and for all, the wall was torn down and rebuilt in 1920. When the sheriff went in to look at the new wall the next day, he was shocked to find the handprint had reappeared.

The Slow Burn

With other mines being opened and operated in the mountains of Pennsylvania and privately owned waterways being built to transport that coal, the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company needed to be competitive. After making the transportation of coal more practical on the Lehigh River, they had to convince the general publicâespecially Philadelphia societyâto purchase it. They knew that once the prominent families of Philadelphia started using anthracite coal regularly, the rest of the region would follow.

Anthracite coal was difficult to ignite and was inefficient as fuel in conventional fireplaces and stoves that had been designed to burn wood. Josiah White and Erskine Hazard began a public relations campaign to convince consumers that anthracite would save them money in the long run. It burned longer, hotter and without smoke. But people needed to have the correct stoves to use the anthracite effectively or the marketing campaign would not be successful.

In 1800, Oliver Evans received a patent for an anthracite stove, but it didn't take off as expected. Before White, Hazard and Hauto took over the Lehigh mining concern, Jacob Cist, facing the same predicament, had designed an anthracite stove simply by converting a Franklin stove. Cist had provided the stove and coal to several prominent families to gain testimonials. It was moderately successful; still, it was difficult to market to the average consumer.

Josiah White sent anthracite to Eliphalet Nott in Schenectady, New York, one of the country's leading combustion experts and stove manufacturers at that time. Nott worked for several years to design an anthracite stove, but didn't file the patent until 1826, which was followed by eleven patents with various improvements.

30

In the end, the Lehigh stove was the first anthracite stove on the market, and it was cast at the Mary Ann Furnace in Bucks County by Reuben Texler.

In 1825, Walter R. Johnson, a professor who worked at the Franklin Institute, developed an air furnace for the stone coal and essentially initiated central heating for homes. Not long after heating stoves were invented, coal stoves for cooking were introduced to Americans.

With an abundance of coal being mined from the mountains and anthracite stoves in many of the homes in Philadelphia, New York and other major cities and surrounding towns, the LC&N had only one more obstacle to overcomeâthe Delaware River.

Chapter 3

Josiah White's Waterways

The LC&N used the Delaware River from Easton to Philadelphia, and in fact, the company's arks spent more time on the Delaware, which they didn't control, than on the Lehigh, which they did. The Delaware was more navigable than the Lehigh, yet the company was still susceptible to loss because of flooding and drought.

Josiah White decided to petition the Pennsylvania legislature to improve the Delaware and turn it into a huge canal with extensively large locks that could accommodate steam-powered ships. He brought in two men, Canvass White (no relation to Josiah) and Benjamin Wright, canal engineers who worked on the Erie Canal, to look over his plans and to inspect the work that had been done on the Lehigh. They read his proposal and were very impressed with his plans, but they admitted that they lacked the experience to help produce a canal of this grand a scheme.

Josiah's extravagant proposal met with many objectionsâone of which was that the Pennsylvania Assembly was already planning a transportation network across the state. Pennsylvania citizens were calling for a system of public transportation to provide access to Philadelphia, not just for the mining industry, but for timber, pig iron and other manufactured goods throughout the commonwealth. In 1825, the legislature established the first official Board of Canal Commissioners, and a second act was passed in 1826 to formally initiate the construction of public canals and railroads. The act gave the commissioners power to begin construction at three points: along the Susquehanna River to the Juniata River; along the Allegheny River from Pittsburgh to the Kiskimineta River; and down the French Creek to connect with Conneaut Lake. These were called the Main Line canals and encompassed 726 miles of waterways, associated railways and inclined plains.

Not ready to give up, Josiah and Erskine offered to construct the Delaware Division Canal at the expense of their company and not charge tolls, but again they were rejected.

Courtesy of Pennsylvania Canal Society Collection, National Canal Museum, Easton, PA

.

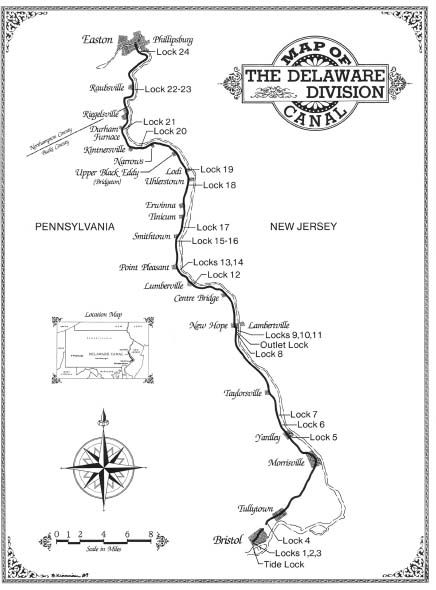

In April 1827, the state decided to build a small canal along the Delaware that would be part of the Main Line canal system. It would be built in the Erie Canal style and would measure 11 feet wide. The canal would link Easton with Bristol at a length of sixty miles and have twenty-four lift locks to correct the 180-foot elevation differential.

As a result, Josiah and Erskine began construction on a less imposing canal along the Lehigh than they had originally wanted to build, although it was still larger than the plans drawn up for the Delaware Division Canal. The Lehigh Canal would be wide enough to accommodate two boats passing each other. It was to be sixty feet wide and five feet deep, and because it was more conventional, Canvass White agreed to oversee the building of the Lehigh Canal. It utilized a series of slack water pools (meaning that boats would leave the canal to go into the river), with a total of forty-four lift locks, five guard locks, three guard lifts, nine dams and several aqueducts over the forty-six miles of navigation.

The Delaware Division Canal, which would run from Bristol to Easton, where it would connect with the Lehigh Navigation Canal, was started a few months after the Lehigh Navigation construction began, and although it was launched with great excitement in Bristol, the preliminary construction of the Delaware Division was essentially a disaster from the beginning.

First, there were confrontations about where the terminus should be located. Bucks County was a rural and agricultural region just north of Philadelphia. Bucks Countians knew that wherever the terminus of the canal would be located, prosperity would follow. The residents who lived in Tullytown believed that Scott's Creek would be the best spot for the canal's connection with the river and appealed to the commissioners. Bristol residents argued that, as it had been a major port since the seventeenth century and the depth of the water in Bristol was sufficient to float vessels carrying five hundred tons (as opposed to two hundred in Scott's Creek), locating the terminus in Bristol made more sense. The commissioners agreed.

Contractors needed to be hired. In their contract, the Board of Canal Commissioners required that the contractor furnish all the tools as well as the men, and a portion of his payment would be withheld until the work was approved. Contracts went to the lowest bidders, not always the best and most reliable.

On October 27, 1827, Bristol was ready to celebrate the turning of the first blade of earth in construction of the canal with great pomp and circumstance. William T. Swift, who had been appointed the grand marshal, marched five hundred men to the spot that would become Lock Number 3 for a prayer by the local Episcopal priest, followed by an address by Peter A. Brown, a prominent member of the Philadelphia bar.

Two men, George Harrison and Peter Ihire, appeared with a pick and shovel and a wheelbarrow. In a symbolic ceremony, Ihire began to dig a trench and throw the dirt in the wheelbarrow, while Harrison wheeled it a short distance away and dumped the dirt in a heap. Swift congratulated the citizens of Bucks County in yet another speech, and the band played “Hail Columbia,” followed by a deafening three cheers by the attendees.

31

The crowd then went to the Delaware House, which was owned by Charles Bessonett, to continue the celebrationâan appropriate venue considering that it was and still is the oldest continuously operated establishment in Bucks County, although it is now called the King George II.

Thomas G. Kennedy was the superintendent of construction and awarded contracts to dig the canal to David Dorrance and Richard Morris of Bristol for the first eighteen miles, from Bristol to Yardleyville (now Yardley). The canal was built primarily by Irish immigrants, who were for the most part unskilled. Local farmers also hired out to dig sections of the canal. The work was very difficult. Their tools were pickaxes, shovels and wheelbarrows, and the laborers were paid between forty to seventy-five cents a day, no matter how many hours they worked. These wages were occasionally supplemented with a bottle of whiskey as a bonus. If they were strong enough and willing to do the work, they were paid extra for digging out tree stumps. At twenty-five cents a tree stump, a hardworking, capable digger could make as much as five to twelve dollars a day. The laborers had the reputation of drinking hard, fighting hard and working hard. They endured bad housing and food and long hours of work. During the construction of the canal, many men died or were killed in accidents. The summer months brought Asiatic cholera, which erupted violently and could kill within days, taking the lives of many laborers, who were quickly replaced by new immigrants waiting for jobs.

After groundbreaking for the Delaware Division Canal in Bristol, a celebration took place in the Delaware Houseâthe oldest continuously run tavern in Bucks County, now called the King George II.

Author's collection

.

Skilled artisans built locks, aqueducts, dams, waste weirs, towpath bridges and weighing locks.

Unlike the privately built and owned Lehigh Navigation Canal, which had Josiah White and the men hired by the LC&N to work under him, the state didn't have as much access to, or they chose not to hire, truly qualified engineers. To be fair, engineers were few and far between in this country since none of the schools offered engineering except West Point. Building canals in this country involved new technology, especially the design of the locks and aqueducts, and as a result, completion of the Delaware Canal took longer than expected.

Faulty workmanship and errors in design continuously interfered with the construction and opening of the canal. In 1830, it was declared complete, but the locks were too small for the boats and there wasn't sufficient water supply to fill the waterway to capacity. Eager to have the Delaware Canal completed because not having access to the lower canal was costing the LC&N huge sums of money, the company tried to help by damming the Lehigh where it met with the Delaware, creating a pool of water to feed the Delaware Canal. Unfortunately, the canal was so badly constructed that when the water entered, it leaked dry and the canal had to be closed.