The Day We Went to War (31 page)

Read The Day We Went to War Online

Authors: Terry Charman

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Military, #World War II, #Ireland

3.00pm, T

RENT

P

ARK

John Colville and his brother Philip, who is awaiting his call-up to the Grenadier Guards, have motored over to Sir Philip Sassoon’s former home. Sir Philip died only three months ago and left Trent Park to his cousin Mrs Gubay. Trent Park has an excellent private twelve-hole golf course which the Colville brothers are now going round. John reflects what a peaceful way it is to spend the first afternoon of a new world war.

3.00pm, O

LYMPIA

E

XHIBITION

H

ALL

, L

ONDON

Eugen Spier and his fellow internees are now joined by Captain Siebert and his crew from the German merchant vessel

Pomona

. They have tried to scuttle their ship in the Port of London after being refused permission to sail. Their arrival now means that anti-Nazis like Spier and Weiss are outnumbered. The newcomers strut around giving the ‘Heil Hitler’ salute and taunt the Jewish internees ‘with the foulest anti-semitic and anti-religious insults’. They boast that the war will be won by Christmas and they will all sail home in ships of the surrendered Royal Navy.

3.00pm, B

ELFAST

In East Bridge Street, a Territorial Army soldier of the 8th (Belfast) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment is set upon by six armed members

of the Irish Republican Army. They strip him of his khaki uniform and burn it before running off.

3.30pm, C

ITY OF

L

ONDON

‘I reported at 3.30 at the [ARP report] centre, passing through unfamiliar streets. Every person had his or her gas mask slung across their shoulders and fireman, policemen and air raid wardens had tin hats and very smart uniforms. Soldiers passed in lorries and the little world I have known so long has disappeared.’ (Vivienne Hall)

3.45pm, B

ELFAST

Another Territorial Army soldier is attacked by the same IRA gang. This time they shoot him in the stomach and he is seriously injured. He is the first British serviceman to be injured in the Second World War.

4.00pm, 10 D

OWNING

S

TREET

Neville Chamberlain has now put together his new administration. Running Britain’s war effort will be the nine-strong War Cabinet. Apart from the Prime Minister himself, it consists of Churchill, now back in office as First Lord of Admiralty, and the two other service ministers, Leslie Hore-Belisha at the War Office and Sir Kingsley Wood, the Secretary of State for Air. Chamberlain’s three closest pre-war colleagues are all also included; Lord Halifax at the Foreign Office, Sir John Simon at the Treasury and Sir Samuel Hoare, who now leaves the Home Office to become Lord Privy Seal. Completing the team are two non-party experts, Admiral of the Fleet Lord Chatfield as Minister for Coordination of Defence and Lord Hankey, Secretary to the War Cabinet in the last war, as Minister without Portfolio. Anthony Eden, now back in office as Dominions Secretary, and Home Secretary Sir John Anderson are also going to be regular attendees.

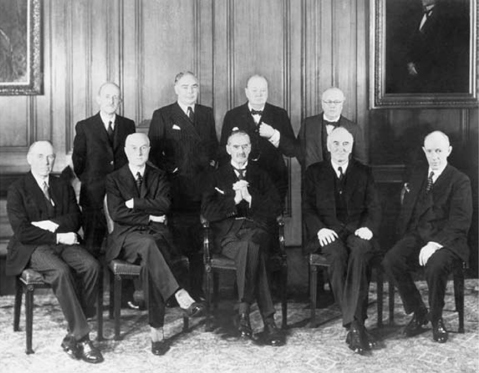

‘Aren’t we a very old team?’ Chamberlain’s War Cabinet.

From left to right (standing):

Lord Hankey (Minister without Portfolio); Leslie Hore-Belisha (Secretary of State for War); Winston Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty); Sir Kingsley Wood (Secretary of State for Air).

From left to right (seated):

Lord Chatfield (Minister for the Co-ordination of Defence); Sir Samuel Hoare (Lord Privy Seal); Neville Chamberlain (Prime Minister); Sir John Simon (Chancellor of the Exchequer) and Lord Halifax (Foreign Secretary).

Apart from Churchill, and, to a lesser extent, Hore-Belisha, it is not a very inspiring collection of personalities to galvanise Britain’s war effort against the Nazis. Chamberlain, as he himself recognises, is not cut out to be a war leader. ‘Holy Fox’ Halifax, ‘Slippery Sam’ Hoare and Simon are all heavily tainted by appeasement. Wood, though efficient and with acute political antennae, is seen as merely a protégé of Chamberlain’s. Chatfield, despite his grand-sounding title, has little political clout, and Hankey, while a great civil servant, is virtually unknown to the general public. As regards Hore-Belisha, many of his cabinet colleagues and the military ‘top brass’ think him ‘publicity mad’ and lacking in substance. His Jewish ancestry also tells against him in the mildly anti-semitic atmosphere of the British Establishment.

Churchill towers over them all. Today has proved that he has been consistently right in his warnings about Hitler’s aggressive designs. He is seen by many as the man who will put both backbone in his colleagues and much-needed drive into the nation’s war effort.

5.00pm,

P

ARIS

S

OIR

OFFICE

, P

ARIS

Editor Pierre Lazareff writes in his diary, ‘This time it’s definite. We’re in. We’re at war. No wild enthusiasm. There’s a job to be done; that’s all. As our men leave to join their regiments they can be heard to say, “We’ve got to put an end to this.”’

Just as in Britain, Lazareff recalls that the French ‘have been told for months now, that “on the very first day of the war, there will be raids on all the big cities . . . and Paris will be destroyed within a few minutes”. A number of citizens have left Paris, but not many. Parisians stroll around with their gas masks slung over their shoulders. Every once in a while, they look up into the sky, but there is no trace of panic. Life goes on.’

4.00pm (5.00pm), B

ERLIN

At the British Embassy all telephone lines are now cut. Sir Nevile and his staff’s only contact is now through the United States Embassy which is now looking after British interests in Germany as the ‘Protecting Power’. In Britain, the Swiss Legation is doing the same for Germany. Outside the Adlon Hotel newsboys are giving away an extra edition of the

Deutsche Allegemeine Zeitung

to passers-by. Its headlines read:

BRITISH ULTIMATUM TURNED DOWN

ENGLAND DECLARES A STATE OF WAR WITH GERMANY

BRITISH NOTE DEMANDS WITHDRAWAL OF OUR TROOPS IN THE EAST

THE FUEHRER LEAVING FOR THE FRONT

TODAY GERMAN MEMORANDUM PROVES ENGLAND’S GUILT

4.00pm (5.00pm), F

RIEDERICHSTRASSE

S

TATION

William and Margaret Joyce see that newspaper extras announcing Britain’s declaration of war are being given away by newsboys under the bridge outside the station. The Joyces join Berliners scrambling for copies. On their faces, Joyce sees no signs of anger or hatred. They just look at each other as if the incredible has just happened.

4.00pm (5.00pm), B

ERLIN

Life

correspondent William Bayles is holding an impromptu drinks party for some other Americans. They celebrate war, Bayle wryly notes, ‘with more complete abandon than we had ever celebrated a diplomatic peace’. They soon polish off a case of champagne.

4.00pm (5.00pm), U

NITED

S

TATES

E

MBASSY

, B

ERLIN

Embassy clerk William Russell notes down some of the rumours flying round the German capital this afternoon:

France will not take part in the war.

Russia has given an ultimatum to England.

The first Italian divisions are already pouring through the Brenner Pass into Germany.

Von Papen is in Paris to negotiate

.

The German and French armies on either side of the Rhine River are fraternizing with each other and have refused to fight

.

It is said that Saarbruecken has been shelled by the French and has been destroyed stone by stone.

None of them turns out to be true.

4.30pm, F

RENCH

G

ENERAL

H

EADQUARTERS

, C

HÂTEAU

D

E

V

INCENNES

French commander-in-chief General Maurice Gamelin sends out secret instructions to France’s armed forces: ‘our ultimatum expires at 5pm today unless the Germans accept it. But to act in accord with the British Air Force we have decided not to commence operations until tomorrow morning at 5am.’

4.30pm, B

ROADCASTING

H

OUSE

Chief Announcer Stuart Hibberd takes a break from reading news bulletins. He goes to Regent’s Park for a breath of fresh air. In the park, Hibberd, who fought at Gallipoli in the last war, looks up to a sky seemingly full of barrage balloons. On the ground he sees an RAF lorry that is securing one of these ‘monster fish’, Hibberd also notices there is a large earth-pin nearby. Dozens of civilians, both men and women, are hard at work, filling sandbags to protect the RAF balloon crew. Pleased to see this sign of national solidarity, Hibberd makes his way back to Langham Place. He has to be on hand for the King’s broadcast at 6.00pm.

5.30pm (6.30pm), F

RENCH

E

MBASSY

, W

ARSAW

At the Frascati Palace, which houses the French Embassy, Ambassador Noël hears, with considerable relief, that his country is now at war with the Third Reich. The mood and size of the crowd outside has diminished since the euphoria of the morning’s announcement of the British declaration. But there is still a large number of Poles outside cheering, and Noël hears snatches of ‘La Marsellaise’ being sung. Colonel Beck now arrives, but his chauffeur finds it difficult to get through the crush of demonstrators outside the embassy’s gates. Beck eventually makes it through. He presents to Noël, with whom he has not enjoyed the best of relations, Poland’s thanks to France for honouring her obligations. The two men have to meet in a small salon on the ground floor of the ornate embassy. The larger reception rooms are being cleared of paintings, furniture and other valuable objects to save them from destruction or damage in air raids. Noël escorts Beck to his car. The French ambassador is surprised that the Colonel is being given such a rapturous reception by the crowd. Until only recently Beck had never gone out into the streets of the capital without a strong escort, his car driven at a high speed. Today he is being acclaimed as the man of the hour.

4.55pm, P

ARIS

The French ultimatum is about to expire and France will soon be at war with Germany. A rumour is circulating around the French capital that Chamberlain and Daladier decided that Britain should be the first to declare war because people in both France and Poland were by no means sure that she would fight.

6.00pm (7.00pm), F

RENCH

E

MBASSY

, W

ARSAW

Now that Beck has gone, Ambassador Noël sets out to make a symbolic gesture towards Franco-Polish solidarity. He is driven across Warsaw to Pilsudski Square to the Tomb of Poland’s Unknown

Warrior. In front of the tomb is a statue of Polish Prince Joseph Poniatowski, a marshal of France who died in 1813, fighting in Napoleon’s ranks. This afternoon, Poles have showered the French embassy with bouquets of flowers. Now Noël lays some of them at the tomb of the Polish Unknown Warrior of the Great War. He also places a wreath at the foot of the Poniatowski statue. In the twilight the ambassador’s gesture is seen by a few passers-by. They appreciate the gesture and call out, ‘

Vive La France.

’

5.00pm, P

ARIS

The French ultimatum to Germany expires and France is now at war with Germany. Just as in Berlin today, there are no scenes of patriotic fervour in the French capital this afternoon comparable to that of 1914. Then the crowds shouted

A Berlin!

(To Berlin!), and threatened to cut off the Kaiser’s moustache. Today, on the café terraces and boulevards, the slogan is the more resigned

Il faut en finir

(We’ve got a put to stop it). Geoffrey Cox, driving down the Boulevard Montmartre in fellow reporter Alan Moorehead’s Ford V8, notices that the crowds are as thick as on a normal Sunday. But their faces are tense, and their steps more hurried today. Suddenly the car splutters and stops. The two men have to get out and push it. In the middle of a stream of impatient horn-blaring traffic Cox quickly glances at his wristwatch. It is just after five o’ clock. France too is now at war.

5.00pm, T

ATE

G

ALLERY

, M

ILLBANK

Director John Rothenstein finishes working. The Tate was closed to the public eleven days ago at midday on 24 August, and the greater part of the Gallery’s collection has now been safely evacuated. While it was being packed up ready to go, Rothenstein received an unexpected visit from the King. He cheerfully tells the Tate’s director, ‘I thought I’d have a look at them before they go, although if it weren’t for those labels of yours, I wouldn’t know one from another. Would you?’