The Day We Went to War (26 page)

Read The Day We Went to War Online

Authors: Terry Charman

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Military, #World War II, #Ireland

11.28am, M

INISTRY OF

E

CONOMIC

W

ARFARE

, L

ONDON

S

CHOOL OF

E

CONOMICS

John Colville and three others are playing bridge in the shelter of the London School of Economics. Colville has visions of London

being reduced to rubble as in the 1936 film of H.G. Wells’s

Things to Come

. But he tries to preserve ‘a semblance of nonchalance’ while playing cards. He and the others are just finishing the first rubber when the ‘All Clear’ goes.

11.28am, A

SHFORD

, K

ENT

Rodney Giesler hears the siren and thinks, ‘Oh, My God, they’re

coming

.’ The family rush down to the cellar to await the bombs, only to emerge when the ‘All Clear’ is sounded.

11.28am, E

ALING

, W

EST

L

ONDON

Elsie Warren, a volunteer in the Auxiliary Fire Service, has just been listening to the Prime Minister on the wireless. She thinks Chamberlain delivered ‘a wonderful speech to the Empire’, but ‘sounded very unhappy’. Now, just as she is going out, the siren sounds. Seeing a friend, Elsie tells her, ‘Hurry up inside . . . that’s the air-raid warning.’ But her friend replies, ‘No, it’s just a test.’ As they begin to argue, a warden comes rushing up the street, blowing his whistle, and people start scurrying off to shelter. Elsie gets on her bicycle and pedals furiously off to Ealing Fire Station. There, she takes up her place by the telephone, but the news soon comes through that ‘it was only a friendly plane that caused the excitement’.

11.28am, M

ITCHAM

, S

URREY

After Chamberlain finishes, Dorothy Tyler’s two brothers decide to go and see some friends to talk things over. Dorothy goes with them. They are just driving off when the siren goes. They turn the car round, and quickly drive back home. Rushing indoors, they grab and put on their gas masks. They then sit down at the kitchen table to wait and see what happens next. Dorothy is worrying about her fiancé, who is in the army. She thinks that he might be sent to fight in Poland.

11.28am, S

MITH

S

QUARE

, W

ESTMINSTER

Home Office civil servant Peter Allen and his wife have just driven up to Westminster to attend morning service when they hear an air-raid warning. An air-raid warden, ‘suddenly conscious of his grave new responsibilities’, ushers the Allens, dutifully clutching their gas masks, into a nearby office block to take shelter. From an upstairs window they can see a barrage balloon going up and then down beyond the roof of Westminster Abbey, ‘rather like a slow moving and inverted yo-yo’. Although he realises that German bombers may very well be on their way, Allen experiences a feeling of relief rather than apprehension. The ‘long preliminaries’ are over at last, and Britain is now engaged ‘in a clear-cut contest in which the end, however distant that might be, would surely result in the destruction of the evil regime which held the world in jeopardy’.

11.28am, B

RIXTON

, S

OUTH

L

ONDON

Britain’s most popular newspaper columnist Godfrey Winn of the

Sunday Express

is in Brixton, intending to buy a motorcycle. He hopes that by having one, with war coming and petrol rationing inevitable, he will still be able to ‘stay mobile’. He is trying out the machine when he hears the ‘first sound of that wailing of the banshee’. Winn, startled and nervous, looks up at the sky, half expecting it to be black with enemy bombers. He promptly falls off straight into the gutter.

11.28am, L

ONDON

Twenty-six-year-old schoolteacher Mary Custance is sitting with her elderly headmistress in the school’s small kitchen-cum-staffroom. They are the only two teachers on the staff, and have been told to report to school each day of the crisis to await further orders. Mary’s headmistress ‘is in great distress of mind about the possibility of war’ and feels that she cannot face the anxiety. Just as she

is unburdening herself to Mary, the school caretaker/cleaner joins them. She tells the two teachers that war has just been declared. No sooner are the words out of her mouth than the sirens begin to sound. Mary’s immediate thought is that they are going to die. But they hurry over to the air-raid shelters, built during the last war, in a nearby works. Like so many others in London today, Mary’s mind has been ‘influenced by science fiction and H.G. Wells’s

The Shape of Things to Come

’. She imagines ‘that everything and everybody will have disappeared into bomb-strewn rubble when they finally emerge.’ But then the ‘All Clear’ sounds, and Mary and her companions emerge into an unscathed London.

11.30am, ‘L

A

C

ROE

’, C

ôTE D

’A

ZUR

At his villa in the south of France, Britain’s former king, Edward VIII, now Duke of Windsor, is impatiently waiting to hear from London. He is anxious to learn how he can best serve his country, just as he had promised he would do in his Abdication speech almost three years ago. The Duke served throughout the Great War. Because of his status he was denied frontline service, but he has always keenly identified with ex-servicemen and they with him. In May this year, he broadcast an eloquent plea for peace and understanding from the former battlefield of Verdun.

And just a few days ago, on 29 August, as ‘a citizen of the world’, he sent a telegram to Hitler, urging him not to plunge the world into war. Now, hearing nothing from London, the Duke and Duchess decide to go for a swim. But just as they are setting off, a servant hurries after them. Sir Eric Phipps, the British ambassador in Paris, is on the telephone, urgently wanting to speak with the Duke. The Duke now hurries back to the house. He is back in a few minutes, rejoins the Duchess and announces, ‘Great Britain has just declared war on Germany, and I’m afraid in the end this may open the way for world Communism.’ He then dives into the pool.

11.30am, F

OREIGN

M

INISTRY

, Q

UAI D

’O

RSAY

, P

ARIS

The ’phone rings on Georges Bonnet’s desk. It is Daladier telephoning from the Ministry of National Defence. He tells Bonnet that the Army Chief of General Staff General Colson has agreed to advance the opening of hostilities by twelve hours to five o’clock this afternoon. Bonnet now has to telephone Ambassador Coulondre in Berlin with fresh instructions.

11.30am, T

EDDINGTON

‘Sirens went off at 11.30. Guns going off. All Clear 11.55.’ (Helena Mott)

11.30am (12.30pm), W

ARSAW

The news has broken that Britain has declared war on Germany. Crowds are swarming out of church after Mass and emptying the city’s cafés. They make their way up Nowy Swiat, Warsaw’s Piccadilly, towards the British Embassy. The crowds are delirious, singing their own versions of ‘God Save the King’ and ‘Tipperary’ as they snatch up one-sheet special editions of the papers that carry blazing headlines announcing Britain’s declaration of war. Union Jacks appear and a group of students carry a huge banner emblazoned with the slogan ‘Cheers for England!’ When the embassy is reached, crowds surge into the shabby little court where grey plaster is peeling off the walls. Boys and young men clamber up the walls and drainpipes and shout for Britain and for France. Ambassador Sir Howard Kennard is not the most demonstrative of men, but he allows himself to appear on the balcony to acknowledge the cheering crowds. Military attaché Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Sword also appears on the balcony several times and raises a glass of champagne to toast the assembled crowd, which now seems to stretch miles down Nowy Swiat.

Flowers are thrown at embassy staff, and anyone British, and also a few Americans, are being slapped on the backs and their

hands pumped by enthusiastic Poles, supremely happy that their country is now no longer alone. Sir Howard is obliged to show himself time and time again on the balcony. Each time he appears he is greeted with prolonged cheering and shouts of ‘Long live Britain!’ and ‘Long live the fight for liberty!’

Suddenly, there is a fresh outburst of cheering as Foreign Minister Colonel Beck arrives. He has come to convey his personal thanks to Britain’s ambassador. The Foreign Minister’s car can barely negotiate its way through the dense crowds. For ten minutes Beck and Sir Howard have to salute each other across a sea of upturned faces, until the Colonel finally manages to enter the embassy building. Beck is offered a drink. But he refuses, saying in French, ‘

Non, le moment est trop triste pour ma patrie

.’ (‘No, this is too sad a moment for my country.’) But he and Kennard appear on the balcony together and shake hands. This sets off the ecstatic crowds again. Sir Howard, in Polish, tells the crowd, ‘Long live Poland. We will fight side by side against aggression and injustice.’ A great roar of approval greets the phlegmatic diplomat’s words. Colonel Beck now tells his fellow countrymen, ‘Britain and Poland have locked hands in a fight for freedom and justice. Britain will not be disappointed in Poland and Poland will not be disappointed in Britain.’

11.30am (6.30pm), H

OLLYWOOD

After a decidedly alcoholic night at the Balboa Yacht Club, David Niven and fellow actor Robert Coote are sleeping it off on their small sloop, the

Huralu

. They are due to join other members of Hollywood’s British colony, including Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, on Douglas Fairbanks Jr’s yacht. Niven and Coote awake to hear a man banging on the side of their boat. He asks them, ‘You guys English?’

Well and truly hung over, the two actors reply, ‘Yes’.

‘Well, lotsa luck – you’ve just declared war on Germany,’ he tells them.

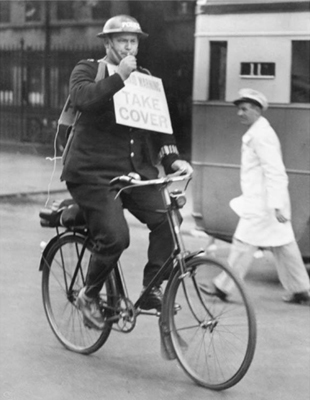

‘Police on bicycles ride up from the police station down the road . . . wearing “Take Cover” placards on chest and back and shout “Take cover”, and “Take cover” is echoed by people in cafés and streets.’ The scene in Whitehall, 11.30am, 3 September 1939.

Not speaking a word to each other, Niven and Coote go below and fill two tea cups with warm gin.

11.42am, HMS

W

ALKER

, S

T

G

EORGE’S

C

HANNEL

Second Officer of the Watch John Adams is given the Admiralty signal, sent out at 11.17am, to ‘commence hostilities at once with Germany’. Adams senses the feeling of immense relief that goes round the bridge of the destroyer at the news. He and the others are all pleased that the decision has at last been made. Now help can be sent to the Poles.

11.45am, O

LYMPIA

E

XHIBITION

H

ALL

, L

ONDON

Eugen Spier and his fellow internees are told by a German-speaking British officer that Britain has been at war with Germany since 11.00am. He tells them that they must elect a camp leader who will act as their spokesman. ‘Putzi’ Hanfstaengl tries to engineer the unanimous election of a known Nazi to the post. He tells his fellow internees, ‘Comrades, we want to show these Englishmen that we are well-disciplined Germans. We want, above all, to keep order and to display the strictest discipline like true German soldiers on the parade ground.’ But Spier steps forward and manages to thwart Hanfstaengl’s ploy. He suggests that they hold a truly democratic election with an alternate candidate. Spier puts forward Dr Weiss as that candidate. The vote takes place and, much to the disgust of the Nazi internees, Weiss duly wins the election.

11.45am, L

IVERPOOL TO

L

EEDS TRAIN

Ninette de Valois and the Sadler’s Wells Ballet Company are travelling from Liverpool to Leeds. En route they pass through a small village station without stopping, but see stuck up on the platform a placard which reads, ‘WAR DECLARED.’ On reaching Leeds, the Company find that the theatre is closed by Government order, and so they now have to return to London.

11.45pm, P

ARIS

Daily Express

staff reporter Geoffrey Cox is making his way by taxi to the

Express

offices in the Rue du Louvre. Cox has already heard that Britain has declared war from an American colleague, Edwin Hartrich. Now he tells his taxi driver of the French ultimatum. The driver reacts with fury. He pours out a stream of obscenities and oaths against Hitler and the Nazis. In his terrible rage, the driving has now become so erratic that Cox has to plead with him, ‘Take it easy. There are eighty million Germans trying to kill us now. There’s no need for you to do the job for them.’

11.48am, RAF S

TATION

W

YTON

Blenheim bomber N6215 of No. 139 Squadron takes off on the Royal Air Force’s first operation of the war. The two-engine bomber is piloted by Flying Officer Andrew McPherson and crewed by an air gunner, Corporal Vincent Arrowsmith, together with an observer from the Royal Navy, Commander Thompson. Its mission is to make a reconnaissance of the German naval base at Wilhelmshaven. This will prepare the way for a later bombing raid. Though reluctant to order attacks on German land targets for fear of killing civilians, the Government are agreed that the German fleet is a legitimate target. Even so there are still a number of provisos in place. The ships may only be attacked if on the high seas, or in the open waters of their bases, but definitely not while still in dockyards.