The Crusades: The Authoritative History of the War for the Holy Land (46 page)

Read The Crusades: The Authoritative History of the War for the Holy Land Online

Authors: Thomas Asbridge

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History, #bought-and-paid-for, #Religion

If Saladin did take Guy for a broken man, he was sorely mistaken. At first the Latin king struggled to make his will felt among the Franks, and Conrad twice refused him entry to Tyre. But by summer 1189, Guy was preparing to make an unexpectedly bold and courageous move.

THE GREAT SIEGE OF ACRE

The blistering heat of midsummer 1189 found Saladin still bent upon the conquest of the intractable stronghold of Beaufort. But in late August news reached him in the foothills of the Lebanese highlands that stirred feelings of dread and suspicion–the Franks had gone on the offensive. In 1187–8 Conrad of Montferrat had played a crucial role defending Tyre against Islam, yet he still baulked at the notion of initiating an aggressive war of reconquest. Secure within the battlements of Tyre, Conrad seemed content to await the advent of the Third Crusade and the great monarchs of Latin Europe–willing, by and large, to wait out the coming war, looking for any opportunity for his own advancement.

Now, the unlikeliest of figures decided to seize the initiative. The disgraced king of Jerusalem, Guy of Lusignan, whose ignominious defeat at Hattin had condemned his realm to virtual annihilation, was attempting the unthinkable. In the company of his redoubtable brother, Geoffrey of Lusignan, a recent arrival in the Levant, as well as a group of Templars and Hospitallers and a few thousand men, Guy was marching south from Tyre towards Muslim-held Acre. He seemed to be making a suicidal attempt to retake his kingdom.

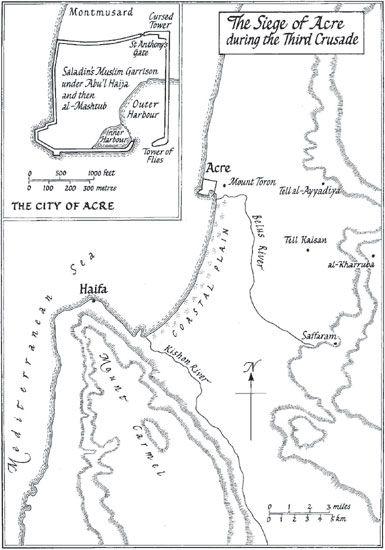

The Siege of Acre during the Third Crusade

At first Saladin greeted this move with scepticism. Believing that it was merely a feint designed to lure him away from Beaufort, he held his ground. This allowed King Guy to negotiate the narrow Scandelion Pass, where, one Frank wrote, ‘all the gold in Russia’ could not have saved them had the Muslims moved to block their advance. Realising his mistake, Saladin began a cautious advance south to Marj Ayun and the Sea of Galilee, waiting to assess the Christians’ next move before turning west towards the coast. Benefiting from his enemy’s circumspection, Guy followed the road south to arrive outside Acre on 28 August 1189.

22

Acre was one of the great ports of the Near East. Under Frankish rule it had become an important royal residence–a vibrant, crowded and cosmopolitan commercial hub, and the main point of arrival for Latin Christian pilgrims visiting the Holy Land. In 1184 one Muslim traveller described it as ‘a port of call for all ships’, noting that ‘its roads and streets are choked by the press of men, so that it is hard to put foot to ground’ and admitting that ‘[the city] stinks and is filthy, being full of refuse and excrement’.

Built upon a triangular promontory of land jutting into the Mediterranean, Acre was stoutly defended by a square circuit of battlements. A crusader later observed that ‘more than a third of its perimeter, on the south and west, is enclosed by the flowing waves’. To the north-east, the landward walls met at a major fortification, known as the Cursed Tower (where, it was said, ‘the silver was made in exchange for which Judas the Traitor sold the Lord’). In the south-east corner the city walls stretched into the sea to create a small chained inner quay, and an outer harbour, protected by a massive wall running north–south that extended to a natural outcrop of rock–the site of a small fortification known as the Tower of Flies. The city stood at the northern end of a large bay arcing south to Haifa and Mount Carmel, surrounded by a relatively flat, open coastal plain, some twenty miles in length and between one and four miles in breadth. About one mile south of the port the shallow Belus River reached the coast.

The city stood at the gateway to Palestine–a bastion against any Christian invasion from the north, by either land or sea. Here Saladin’s resilience, martial genius and

jihadi

dedication would be tested to the limit, as Islam and Christendom became caught up in one of the most extraordinary sieges of the crusades.

23

Early encounters

When King Guy reached Acre his prospects were incredibly bleak. One Frankish contemporary remarked that he had placed his meagre force ‘between the hammer and the anvil’, another that he would need a miracle to prevail. Even the Muslim garrison apparently felt no fear and began jeering from Acre’s battlements when they caught sight of the ‘handful of Christians’ accompanying the king. But Guy immediately demonstrated that he was developing a more acute sense of strategy; having surveyed the field that night, under the cover of darkness, he took up a position on top of a squat hill called Mount Toron. Some 120 feet high, lying three-quarters of a mile east of the city, this tell afforded the Franks a measure of natural protection and a commanding view over the plain of Acre. Within a few days a group of Pisan ships arrived. In spite of the punishing siege to come, many of the Italian crusaders on board had brought their families with them. These hardy men, women and children proceeded to land on the beach south of Acre and make camp.

24

The measured pace of Saladin’s advance to the coast almost had disastrous consequences. Outnumbered and exposed as he was outside Acre, Guy decided to risk an immediate frontal assault on the city even though, as yet, he had no catapults or other siege materials. On 31 August the Latins attacked, mounting the walls with ladders, protected only by their shields, and might have overrun the battlements had not the appearance of the sultan’s advance scouts on the surrounding plain prompted a panicked retreat. Over the next few days Saladin arrived with the remainder of his troops, and any hopes the Latins entertained of forcing a speedy capitulation of Acre evaporated; instead, they faced the dreadful prospect of a war on two fronts–and the near-certainty of destruction at the hands of the victor of Hattin.

Yet, at the very moment that Saladin needed to act with decisive assurance, he wavered. Allowing Guy to reach Acre had proved to be a mistake, but the sultan now made an even graver error of judgement. True, Saladin lacked overwhelming numerical superiority, but he outnumbered the Franks and, through a carefully coordinated attack in conjunction with Acre’s garrison, he could have surrounded and overwhelmed their positions. As it happened, he adjudged a rapid, committed assault to be too risky and instead took up a cautious holding position on the hillside of al-Kharruba, about six miles to the south-east, overlooking the plain of Acre. Unbeknownst to the Latins, he managed to sneak a detachment of troops (presumably shielded by the darkness of night) into the city to bolster its defences and, while skirmishers were dispatched regularly to harass Guy’s camp on Mount Toron, Saladin chose to hold back the bulk of his forces and wait patiently for reinforcement by his allies. On this occasion, such caution, so often the hallmark of the sultan’s generalship, was inappropriate, the product of a significant misreading of the strategic landscape. One crucial factor meant that Saladin could ill afford to bide his time–the sea.

When Saladin reached Acre in early September 1189, the city was invested by Guy’s army and the Pisans. But in the aftermath of Hattin and the fall of Jerusalem, it was almost inevitable that the Frankish siege of this coastal port would become the central focus of Latin Europe’s retaliatory anger. During an inland siege, the king’s forces could have been readily isolated from supply and reinforcement, and Saladin’s circumspection would have made sense. At Acre, the Mediterranean acted like a pulsing, unstemmable artery, linking Palestine with the West, and while the sultan waited for his armies to assemble, ships began to arrive teeming with Christian troops to bolster the besieging host. Imad al-Din, then in Saladin’s camp, later described looking out over the coast to see a seemingly constant stream of Frankish ships arriving at Acre and a growing fleet moored by the shoreline ‘like tangled thickets’. This spectacle unnerved the Muslims inside and outside the port, and to boost morale Saladin apparently circulated a story that the Latins were actually sailing their ships away every night and ‘when it was light…[returning] as if they had just arrived’. In reality, the sultan’s prevarication gave Guy a desperately needed period of grace in which to amass manpower.

25

A significant group of reinforcements arrived around 10 September–a fleet of fifty ships, carrying some 12,000 Frisian and Danish crusaders as well as horses. The western sources describe its advent as a moment of salvation, a tipping point beyond which the Latin besiegers had at least some chance of survival. Among the new troops was James of Avesnes, a renowned warrior from Hainaut (a region on the modern border between France and Belgium). Likened by one contemporary to ‘Alexander, Hector and Achilles’, a skilled veteran in the art of war and the politics of power, James had been one of the first western knights to take the cross in November 1187.

In the course of September, crusaders continued to arrive, swelling the ranks of the Frankish army. Among their number were potentates drawn from the upper ranks of Europe’s aristocracy. Philip of Dreux, the bishop of Beauvais, said to be ‘a man more devoted to battles than books’, and his brother Robert of Dreux came from northern France, as did Everard, count of Brienne, and his brother Andrew. They were joined by Ludwig III of Thuringia, one of Germany’s most powerful nobles. By the end of the month even Conrad of Montferrat had decided, apparently at Ludwig’s insistence, to come south from Tyre to join the siege, bringing with him some 1,000 knights and 20,000 infantry.

26

Saladin too was receiving an influx of troops. By the second week of September the bulk of the forces summoned to Acre had arrived. Joined by al-Afdal, al-Zahir, Taqi al-Din and Keukburi, the sultan moved on to the plain of Acre, taking up position on an arcing line running from Tell al-Ayyadiya in the north, through Tell Kaisan (which later became known as the Toron of Saladin) to the Belus River in the south-west. Just as he settled into this new front, the Franks tried to throw a loose semi-circular cordon around Acre–running from the northern coast, through Mount Toron and across the Belus (which served as a water supply) to the sandy beach to the south. Saladin saw off this first Latin attempt at a blockade with relative ease. As yet, the crusaders lacked the resources to effectively seal off every approach to the city, and a combined assault by Acre’s garrison and a detachment of troops under Taqi al-Din broke the weakest part of their lines to the north, enabling a camel train of supplies to enter the city via St Anthony’s Gate on Saturday 16 September.

By mid-morning that day Saladin himself had entered Acre, climbing its walls to survey the enemy camp. Looking down from the battlements upon the thronged crusader host huddled on the plain below, now surrounded by a sea of Muslim warriors, he must have felt a sense of assurance. With the city saved, his patiently amassed army could turn to the task of annihilating the Franks who so arrogantly had thought to threaten Acre, and victory would be achieved. But the sultan had waited too long. For the next three days his troops repeatedly sought either to overrun the Latin positions or to draw the enemy into a decisive open battle, all to no avail. In the weeks since King Guy’s arrival the swelling crusader ranks had dug into their positions, and they now repulsed all attacks. One Muslim witness described them standing ‘like a wall behind their mantlets, shields and lances, with levelled crossbows’, refusing to break formation. As the Christians clung with stubborn tenacity to their foothold outside Acre, the strain of the situation began to tell on Saladin. One of his physicians revealed that the sultan was so racked with worry that he barely ate for days. Frankish indomitability soon prompted indecision and dissension within Saladin’s inner circle. With some advisers arguing that it would be better to await the arrival of the Egyptian fleet and others advocating that the approaching winter should be allowed to wreak its depredations upon the crusaders, the sultan wavered, and the attacks on the Christian lines ground to a halt. A letter to the caliph in Baghdad offered a positive summary of events–the Latins had arrived like a flood, but ‘a path had been cut to the city through their throats’ and they now were all but defeated–but in reality, Saladin must have begun to realise that the siege of Acre might prove difficult to lift.

27

The first battle

The weeks that followed saw intermittent skirmishing, while Frankish ships continued to bring more and more crusaders to the siege. By Wednesday 4 October 1189 the Christians were numerous enough to contemplate going on the offensive, launching an attack on Saladin’s camp in what was to be the first full-scale pitched battle of the Third Crusade. Leaving his brother Geoffrey to defend Mount Toron, King Guy amassed the bulk of the Frankish forces at the foot of the tell, carefully drawing up an extended battle line with the help of the Military Orders and potentates such as Everard of Brienne and Ludwig of Thuringia. With infantry and archers in the front ranks, screening the mounted knights, the Christians set out to cross the open plain towards the Muslims, marching in close order and at slow pace. This was to be no lightning attack, but, rather, a disciplined advance in which the crusaders tried to close with the enemy en masse, protected by their tightly controlled formation. Surveying the field from his vantage point atop Tell al-Ayyadiya, Saladin had ample time to arrange his own forces on the plain below, interspersing squadrons under trusted commanders like al-Mashtub and Taqi al-Din with relatively untested troops, such as those from Diyar Bakr on the Upper Tigris. Holding the centre with Isa, but looking to play a mobile command role, boosting morale and discipline where necessary, the sultan prepared to face the Franks.