The Crimean War (47 page)

Authors: Orlando Figes

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Europe, #Other, #Russia & the Former Soviet Union, #Crimean War; 1853-1856

In his capacity of Secretary at War, Herbert appointed Nightingale as superintendent of the Female Nursing Establishment of the English General Hospitals in Turkey, though not in the Crimea, where she had no authority until the spring of 1856, when the war was almost at an end. Nightingale’s position was precarious: officially she was subordinated to the military hierarchy, but Herbert gave her instructions to report to him on the failures of the Army Medical Department, and her whole career would depend on fighting tooth and nail against its bureaucracy, which was basically opposed to female nurses at or near the front. Nightingale was domineering by nature but she needed to assume a dictatorial control over her nurses if she was to implement her organizational changes and gain the respect of the military establishment. There was no recognized body of professional nurses from which she could draw her team in Turkey, so with the help of Mrs Herbert she had to establish one herself. Her selection criteria were ruthlessly functional: she favoured younger women from the lower classes, who she thought would buckle down to the hard work and conditions that lay ahead; and she took a group of nuns with experience of nursing to supervise their work, regarding them as a practical concession to the Irish Catholics who made up one-third of the army’s rank and file; but she rejected hundreds of applications from well-meaning middle-class women, whose sensitivities she feared would make them ‘less manageable’.

Nightingale and her team of thirty-eight nurses arrived in Scutari on 4 November 1854, just in time for the mass transport of the wounded from the battle of Balaklava. The French had already taken over the best buildings for their hospitals, and those left for the British were badly overcrowded and in a dreadful state. The wounded and the dying were lying all together with the sick and the diseased on beds and mattresses crammed together on the filthy floor. With so many men suffering from diarrhoea, the only toilet facilities were large wooden tubs standing in the wards and corridors. There was almost no water, the old pipes having broken down, and the heating system did not work. Within days of Nightingale’s arrival, the situation became much worse, as hundreds more wounded men from the battle of Inkerman flooded the hospital. The condition of these men was ‘truly deplorable’, as Walter Bellew, an assistant surgeon at the Hyder Pasha Hospital near Scutari, noted in his diary: ‘Many were landed dead, several died on the way to the hospitals, and the rest were all in a most pitiable condition; their clothes were begrimed with filth and alvine evacuations [from the abdomen], their hands and faces blackened with gunpowder & mud &c and their bodies literally alive with vermin.’ The men were dying at a rate of fifty to sixty every day: as soon as one man breathed his last he was sewn into his blanket and buried in a mass grave by the hospital while another patient took his bed. The nurses worked around the clock to feed and wash the men, give them medicines, and bring them comfort as they died. Many of the nurses were unable to cope with the strain and began drinking heavily, some of them complaining about the bossy manner of Miss Nightingale and about their menial work. They were sent home by Nightingale.

28

28

By the end of December Nightingale had a second team of nurses at her disposal, and control of the

Times

Crimean Fund, enabling her to purchase stores and medicines for all the British hospitals in Scutari. She was able to act on her own initiative, without obstruction from the military authorities, who relied on her financial and administrative power to rescue them from the medical disaster they were in. Nightingale was an able administrator. Although her impact has been overestimated (and the contribution of the British medical officers, dressers and dispensers almost totally ignored) by those who later made her cult, there is no doubt that she got things moving in the main hospital at Scutari. She reorganized the kitchens, purchased new boilers, hired Turkish laundresses and supervised their work, oversaw the cleaning of the wards, and after working twenty hours every day, would make her nightly rounds, bringing words of Christian comfort to the men, for which she became known as the Lady with the Lamp. Yet despite all her efforts, the death rate continued to escalate alarmingly. In the month of January, 10 per cent of the entire British army in the East died from disease. In February, the death rate of patients at Scutari was 52 per cent, having risen from 8 per cent when Nightingale arrived in November. In all, that winter, in the four months following the hurricane, 4,000 soldiers died in the hospitals of Scutari, the vast majority of them unwounded. The British public was appalled by the loss of life. The readers of

The Times

demanded explanations, and in early March a government-appointed sanitary commission arrived in Scutari to investigate. It found that the main Barrack Hospital was built on top of a cesspool, that the sewers were leaking, with sewage spilling into the drinking water. Nightingale was unaware of the danger, for she believed that infection came from contaminated vapours, but the sanitation in the hospital was clearly inadequate. The soldiers in her care would have had a better chance of survival in any Turkish village than in her hospitals in Scutari.

Times

Crimean Fund, enabling her to purchase stores and medicines for all the British hospitals in Scutari. She was able to act on her own initiative, without obstruction from the military authorities, who relied on her financial and administrative power to rescue them from the medical disaster they were in. Nightingale was an able administrator. Although her impact has been overestimated (and the contribution of the British medical officers, dressers and dispensers almost totally ignored) by those who later made her cult, there is no doubt that she got things moving in the main hospital at Scutari. She reorganized the kitchens, purchased new boilers, hired Turkish laundresses and supervised their work, oversaw the cleaning of the wards, and after working twenty hours every day, would make her nightly rounds, bringing words of Christian comfort to the men, for which she became known as the Lady with the Lamp. Yet despite all her efforts, the death rate continued to escalate alarmingly. In the month of January, 10 per cent of the entire British army in the East died from disease. In February, the death rate of patients at Scutari was 52 per cent, having risen from 8 per cent when Nightingale arrived in November. In all, that winter, in the four months following the hurricane, 4,000 soldiers died in the hospitals of Scutari, the vast majority of them unwounded. The British public was appalled by the loss of life. The readers of

The Times

demanded explanations, and in early March a government-appointed sanitary commission arrived in Scutari to investigate. It found that the main Barrack Hospital was built on top of a cesspool, that the sewers were leaking, with sewage spilling into the drinking water. Nightingale was unaware of the danger, for she believed that infection came from contaminated vapours, but the sanitation in the hospital was clearly inadequate. The soldiers in her care would have had a better chance of survival in any Turkish village than in her hospitals in Scutari.

In Britain, France and Russia, the public followed these developments with increasing interest and concern. Through daily reports in the newspapers, photographs and drawings in periodicals, people had immediate access to the latest news about the war, and a clearer grasp of its realities, than during any previous conflict. Their reactions to the news became a major factor in the calculations of the military authorities, which were exposed to a degree of public criticism never seen before during wartime. This was the first war in history in which public opinion played so crucial a role.

Britain led the way in terms of its appetite for news. Reports of the suffering of the troops and the plight of the wounded and the sick had created a state of national anxiety about the situation of the allied armies camped above Sevastopol. The severe frost in Britain that winter served only to intensify these feelings of concern for the men out in Russia. There was a huge response to the

Times

Crimean Fund, as well as to the Royal Patriotic Fund for the relief of the soldiers’ wives and families, with people from all walks of life donating money, sending food parcels, and knitting warm clothing (including the ‘Balaklava Helmets’ that were invented at this time). The Queen herself informed the Duke of Cambridge that ‘the whole female part’ of Windsor Castle, including herself, was ‘busily knitting for the army’.

29

Times

Crimean Fund, as well as to the Royal Patriotic Fund for the relief of the soldiers’ wives and families, with people from all walks of life donating money, sending food parcels, and knitting warm clothing (including the ‘Balaklava Helmets’ that were invented at this time). The Queen herself informed the Duke of Cambridge that ‘the whole female part’ of Windsor Castle, including herself, was ‘busily knitting for the army’.

29

More than any other country on the Continent, Britain enjoyed a free press, and that freedom now showed its face. The abolition of the newspaper stamp duty in 1855 enabled the growth of a cheaper press, afforded even by the working man. As well as many letters from officers and soldiers, the Crimean War saw the emergence of a new breed of ‘war correspondent’, who brought the events of the battlefield to the breakfast tables of the middle class. During previous wars, newspapers had relied on amateur ‘agents’ – usually diplomats or approved officers in the armed forces – to send in reports (a tradition that lasted until the end of the nineteenth century when a young Winston Churchill reported on the Sudan as a serving army officer). These reports were normally drawn from military communiqués, and they were subject to the censorship of the authorities; it was rare for an agent to include a first-hand account of events he had himself witnessed. Things began to change in the 1840s and early 1850s, as newspapers started to employ foreign correspondents in important areas, such as Thomas Chenery, the

Times

correspondent in Constantinople since March 1854, who broke the news of the appalling conditions in the hospitals of Scutari.

30

Times

correspondent in Constantinople since March 1854, who broke the news of the appalling conditions in the hospitals of Scutari.

30

The advent of steamships and the telegraph enabled newspapers to send their own reporters into a war zone and print their stories within days. News travelled faster during the Crimean War as telegraphs were built in stages to link the battle zone with the European capitals. At the start of the campaign in the Crimea the fastest news could get to London in five days: two by steamship from Balaklava to Varna, and three by horseback to Bucharest, the nearest link by telegraph. By the winter of 1854, with the French construction of a telegraph to Varna, news could be communicated in two days; and by the end of April 1855, when the British laid an underwater cable between Balaklava and Varna, it could get to London in a few hours.

ap

ap

It was not just the speed of news that was important but the frank and detailed nature of the press reports that the public could read in the papers every day. Free from censorship, the Crimean correspondents wrote at length for a readership whose hunger for news about the war fuelled a boom in newspapers and periodicals. Through their vivid descriptions of the fighting, of the terrible conditions and suffering of the men, they brought the war into every home and allowed the public to be actively involved in the debate about how it should be fought. Never had so many readers written to

The Times

and other newspapers as they did in the Crimean War – nearly all of them with observations and opinions about how to improve the campaign.

aq

Never had so many of the British middle classes been so politically mobilized. Even remote country areas were suddenly exposed to world events. In his winning memoirs, the poet Edmund Gosse recalls the impact of the war on his family, reclusive members of a small Christian sect in the Devon countryside: ‘The declaration of war with Russia brought the first breath of outside life into our Calvinist cloister. My parents took in a daily newspaper, which they had never done before, and events in picturesque places, which my Father and I looked out on the map, were eagerly discussed.’

31

The Times

and other newspapers as they did in the Crimean War – nearly all of them with observations and opinions about how to improve the campaign.

aq

Never had so many of the British middle classes been so politically mobilized. Even remote country areas were suddenly exposed to world events. In his winning memoirs, the poet Edmund Gosse recalls the impact of the war on his family, reclusive members of a small Christian sect in the Devon countryside: ‘The declaration of war with Russia brought the first breath of outside life into our Calvinist cloister. My parents took in a daily newspaper, which they had never done before, and events in picturesque places, which my Father and I looked out on the map, were eagerly discussed.’

31

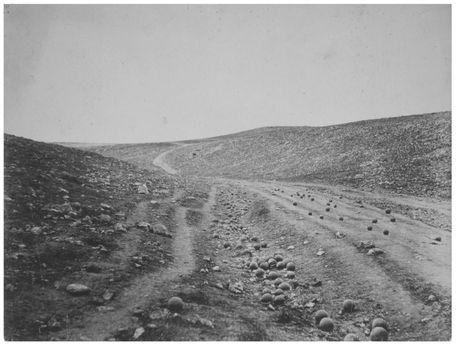

The public appetite for vivid descriptions of the Crimean campaign was insatiable. War tourists like Fanny Duberly had a ready readership for their eyewitness narratives. But the greatest interest was reserved for visual images. Lithographs were quick and cheap enough to reproduce in periodicals like the

Illustrated London News

, which enjoyed a huge boom in its weekly sales during the Crimean War. Photographs aroused the interest of the public more than anything – they seemed to give a ‘realistic’ image of the war – and there was a substantial market for the photographic albums of James Robertson and Roger Fenton, who both made their names in the Crimea. Photography was just entering the scene – the British public had been wowed by its presentation at the Great Exhibition of 1851 – and this was the first war to be photographed and ‘seen’ by the public at the time of its fighting. There had been daguerreotypes of the Mexican-American War of 1846–8 and calotypes of the Burmese War of 1852–3, but these were primitive and hazy images compared to the photographs of the Crimean War, which appeared so ‘accurate’ and ‘immediate’, a ‘direct window onto the realities of war’, as one newspaper remarked at the time. In fact they were far from that. The limitations of the wetplate process (which required the glass plate to be exposed for up to twenty seconds) made it virtually impossible to photograph movement (though techniques improved to make this possible by the time of the American Civil War in the early 1860s). Most of Robertson’s and Fenton’s photographs are posed portraits and landscapes, images derived from genres of painting appealing to the tastes and sensibilities of their middle-class market. Although both men had seen a lot of death, neither showed it in their photographs – though Fenton referred to it symbolically in his most famous picture,

Valley of the Shadow of Death

, a desolate landscape strewn with cannonballs (which he clustered together to intensify the image) – because their pictures needed to be reconciled with Victorian society’s prevailing notions of it as a just and righteous war. The sanitized depiction of war in Robertson’s work had more to do with commercial pressures than with any censorship, but in the case of Fenton, a royal photographer who was sent to the Crimea partly to counteract the negative depiction of the campaign in

The Times

and other newspapers, there was certainly an element of propaganda. To reassure the public that the British soldiers were warmly dressed, for example, Fenton took a portrait of some soldiers dressed in good boots and heavy sheepskin coats recently dispatched by the government. But Fenton did not arrive in the Crimea until March 1855, and that portrait was not taken until mid-April, by which time many lives had been lost to the freezing temperatures and the need for such warm clothing had long passed. With April temperatures of 26 degrees, Fenton’s soldiers must have been sweltering in the heat.

32

Illustrated London News

, which enjoyed a huge boom in its weekly sales during the Crimean War. Photographs aroused the interest of the public more than anything – they seemed to give a ‘realistic’ image of the war – and there was a substantial market for the photographic albums of James Robertson and Roger Fenton, who both made their names in the Crimea. Photography was just entering the scene – the British public had been wowed by its presentation at the Great Exhibition of 1851 – and this was the first war to be photographed and ‘seen’ by the public at the time of its fighting. There had been daguerreotypes of the Mexican-American War of 1846–8 and calotypes of the Burmese War of 1852–3, but these were primitive and hazy images compared to the photographs of the Crimean War, which appeared so ‘accurate’ and ‘immediate’, a ‘direct window onto the realities of war’, as one newspaper remarked at the time. In fact they were far from that. The limitations of the wetplate process (which required the glass plate to be exposed for up to twenty seconds) made it virtually impossible to photograph movement (though techniques improved to make this possible by the time of the American Civil War in the early 1860s). Most of Robertson’s and Fenton’s photographs are posed portraits and landscapes, images derived from genres of painting appealing to the tastes and sensibilities of their middle-class market. Although both men had seen a lot of death, neither showed it in their photographs – though Fenton referred to it symbolically in his most famous picture,

Valley of the Shadow of Death

, a desolate landscape strewn with cannonballs (which he clustered together to intensify the image) – because their pictures needed to be reconciled with Victorian society’s prevailing notions of it as a just and righteous war. The sanitized depiction of war in Robertson’s work had more to do with commercial pressures than with any censorship, but in the case of Fenton, a royal photographer who was sent to the Crimea partly to counteract the negative depiction of the campaign in

The Times

and other newspapers, there was certainly an element of propaganda. To reassure the public that the British soldiers were warmly dressed, for example, Fenton took a portrait of some soldiers dressed in good boots and heavy sheepskin coats recently dispatched by the government. But Fenton did not arrive in the Crimea until March 1855, and that portrait was not taken until mid-April, by which time many lives had been lost to the freezing temperatures and the need for such warm clothing had long passed. With April temperatures of 26 degrees, Fenton’s soldiers must have been sweltering in the heat.

32

Valley of the Shadow of Death

(1855)

(1855)

Other books

The Alpha's Onyx & Fire by Jess Buffett

Exposure by Elizabeth Lister

Me and My Shadow by Katie MacAlister

04 The Edge of Darkness by Tim Lahaye

Captive by Aishling Morgan

Wild Swans by Patricia Snodgrass

Disturb by Konrath, J.A.

"Who Could That Be at This Hour?" (All the Wrong Questions) by Snicket, Lemony

Tempest in Eden by Sandra Brown

Nickels by Karen Baney