The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment (14 page)

Read The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment Online

Authors: Chris Martenson

Tags: #General, #Economic Conditions, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Development, #Forecasting, #Sustainable Development, #Economic Development, #Economic Forecasting - United States, #United States, #Sustainable Development - United States, #Economic Forecasting, #United States - Economic Conditions - 2009

Too Much Debt

Now that we understand the differences between debts and liabilities, can tell good debt from bad debt, and know that debt has been growing far faster than national income (i.e., GDP), we’re ready to dive one layer deeper into the debt data as the final step toward assessing the severity and magnitude of the economic predicament.

The pure debt obligations of the U.S. government as of October 2010 stood at $13.7 trillion.

3

But this is only the debt. Once we add in the liabilities of the U.S. government, chiefly Medicare and Social Security, we get a number somewhere between $100 trillion and $200 trillion dollars, depending on whether you use the Federal Reserve’s own estimates or those of Boston University economics professor Laurence J. Kotlikoff, respectively.

4

As mentioned before, these liabilities can be changed at any time with the stroke of a congressional pen, but one thing to remember is that entitlements are a zero sum game. In other words, if the government decides to save money by slashing benefits, the result will be a lower standard of living for the recipients of those monies. The government will see budget savings, to be sure, but retirees will experience a reduction in cash flows and in their living standards. Savings in one place translate into losses elsewhere. That’s the essence of “zero sum.”

But it’s not just the federal government that has underfunded liabilities totaling in the trillions of dollars. States and municipalities are also deeply underwater on their pension promises. Once we add up all the debts and liabilities of the United States, we discover that they are more than 10 times larger than GDP. How many historical examples can we look upon where a country managed to gracefully grow its way out from under such an enormous pile of unfunded paper promises? None. There are zero historical examples to guide us. The world-record holder in this regard is England, which managed to pull itself out of debt during the period from 1820 to 1900, but its debt load was only 2.6 times its GDP and the Industrial Revolution came along to help out. We will discuss this example more in Chapter 12 (

Like a Moth to a Flame

).

Debt’s Big Assumption

As troubling as all that is, the story of debt extends well beyond the idea that there is too much of it. To understand why, let’s look at the role of debt and how it relates to the future.

Consumptive debt, or debt that’s not self-liquidating, provides us with money to spend today. Perhaps we buy a nicer car, and we enjoy that car today. But future auto loan payments will represent money that we’ve already spent in the past and won’t be able to spend in the future. Put simply, debt enables future consumption to be taken today, not tomorrow. In this sense, debt is a claim on future money, and therefore debt is really just a fancy way of pulling money from the future so that we can spend it today.

We learned in Chapter 7 (

Our Money System

) that money can be viewed as a claim on wealth, and we just learned that debt is just a claim on future money. We can put these statements together and arrive at this important conclusion:

Debt is a claim on future wealth

. This implies that a constantly growing level of debt, like the one we have collectively experienced (and participated in) in the decades since 1980, has an enormous and unavoidably gigantic assumption baked right into it.

Ever-Growing Debt’s Massive Assumption

Go back and take one more look at the upwardly sloping line that represents debt-to-GDP in

Figure 10.2

. The critical assumption inherent in that slope is this: The economic future will be—

must be

—exponentially larger than the present.

Logically, if debt represents a claim on the future, then ever-larger amounts of debt represent ever-larger claims on the future. Okay, that sounds easy enough. But let’s recall that debt carries with it the expectation of repayment of both the principal and the interest components. If the debt has a principal balance of “X,” we must not forget that the interest component is a percentage increase based on “X.” How do we describe something that grows by some percentage over time? That’s right—we say it’s growing exponentially.

Therefore, each incremental expansion of the level of debt is an explicit assumption that the future will be larger than the present. And not just a little bit larger—the future will need to be

exponentially

larger than the present for debts to be fully paid back and not defaulted upon.

Given that U.S. debts now represent over 360 percent of GDP and total liabilities over 1000 percent of GDP, there’s an explicit assumption being made by the debt markets that the future GDP of the United States is going to be larger than today’s GDP. A

lot

larger. More cars must be sold, more resources consumed, more money earned, more houses built—

every

facet of economic growth and complexity must increase simply to pay back the loans that are already booked. Any continuation of debt expansion will compound these claims on the future. Now think back to that Stage Two line on the Debt-to-GDP chart in

Figure 10.2

and ask yourself how likely it seems that the United States will be able to engineer another 20 years of faster-than-income (GDP) debt expansion.

Banks, pension funds, and government solvency, whose futures are intimately tied to the continued exponential expansion of debt, all have an enormous stake in its perpetual growth. This defines the pressure to continue the expansion and explains why our fiscal and monetary authorities seem to talk of nothing but economic growth. Without economic growth, further debt expansion does not make any sense. Without continued debt expansion, large-scale debt defaults emerge and the financial system begins to break down. The tension that stalks the financial and economic markets results from the conflict between (a) the fact that preserving the status quo

requires

(there’s that word again) the continuous and uninterrupted growth in debt and (b) the fact that nothing can continue to grow forever. That’s the essential conflict. Each of us already knows deep down which side of that conflict will win that battle.

How It Unfolds

But what happens when the debt markets finally figure out that the future cannot grow to infinity? What then? Well, broadly speaking, when that day comes to pass, there can only be one outcome, although it could arrive in either of two different forms. The outcome is simply that a lot of what we think of as wealth simply must vanish, because the claims are too numerous and potential future growth is too little. This destruction of wealth can come about in one of two very opposite ways. The first is by deflation, manifested as a process of debt defaults, and the second is by inflation.

Defaults are easy to explain—the debts don’t get repaid and the holders of that debt don’t get their money back. Boom—over and done. The claims are diminished. Thus, if the future isn’t large enough to pay back the claims, then defaults are simply a way of squaring up past claims with current reality. This path is easy to understand. Perhaps a pension fund holds a billion dollars of General Motors debt, GM goes out of business, GM debt goes into default and becomes worthless, and pensioners in the future have a billion fewer dollars distributed to them, dragging down their standards of living.

However, the inflation route can be confusing. Think of it this way: Imagine that you sold your house to someone, and, to keep it simple, you provided them with a mortgage for $500,000. The terms call for the mortgage to be repaid all at once in 10 years as a single payment of $650,000, providing you with a nice kicker of $150,000, which amounts to something above the prevailing rate of interest. So far, so good. Well, 10 years passes, and, as stipulated, you are paid your $650,000 right on time. But now, due to inflation, that $650,000 will only buy a house half as nice as the one you sold. Yes, you got paid, but your claim on the future was vastly diminished by inflation. In this example, $650,000 in the future buys half as much as $500,000 today.

In the default scenario, your money is still worth something, but you don’t get it back, which also diminishes your claim on the future. In the inflation scenario, you do get your money back, but it hardly buys anything, which also diminishes your claim on the future. In both cases you have less wealth in the future, so the impacts are very nearly the same, but the mechanisms by which you lose out are remarkably different.

- Have too many claims been made on the future?

- If so, will we face inflation or defaults as the means of squaring things up?

You’ll arrive at wildly different life decisions depending on whether you answer yes or no to the first question and “inflation” or “defaults” for the second question. I strongly recommend that you spend some time pondering these questions and revisiting them as circumstances shift.

1

1

This is a complicated subject and one that requires constant vigilance, as its ultimate outcome is not mathematically defined, but is the product of unknowable decisions by fiscal and monetary authorities. At

www.ChrisMartenson.com

, this is one of the most vigorous areas of debate, and our assessment of which outcome is most likely varies considerably. In short: If you expect inflation, you will seek to get rid of your money as fast as possible by spending it on things that have value to you today and which you suspect will cost you even more tomorrow. If you expect deflation, your correct strategy is to hoard your money carefully, as it will be harder to come by and will grow in relative value with every passing day. My own assessment in the closing months of 2010 is that inflation vs. deflation for U.S. citizens has an 80/20 probability.

CHAPTER 11

The Great Credit Bubble

In order to understand what the future may hold, we need to see the excessive accumulation of debt between the early 1980s and 2010 for what it really was—an enormous and protracted credit bubble. Debt levels doubled, redoubled, and doubled again with uncanny mathematical precision. Within that larger credit bubble, we had several minibubbles—one in stocks and the other in housing—and while these were both financially destructive, they were sideshows on the way to the main act.

Because our hopes and dreams for the future rest upon a well-functioning economy, we need to understand what bubbles are and the financial risks they pose. If my analysis is correct, the main bubble has only just begun to burst. Under the best of circumstances, this will exert profound influences for a long time to come; under less favorable circumstances, it will prove to be a uniquely unfortunate and disruptive period of economic adjustment.

Because this past episode of credit expansion was so ubiquitous (it spanned the globe) and lasted for so long (30 years), it came to be accepted as normal and logical by otherwise bright and intelligent people. Like all credit bubbles, this one was founded on the most enduring of human weaknesses: the desire to get something for nothing.

Before we dive into the Great Credit Bubble, let’s spend a bit of time defining what an asset bubble is and examining some of the more common characteristics of bubbles.

What Is a Bubble?

Along the continuum of irrational financial behavior, it can be tricky to tell the difference between a bubble, a mania, and a touch of overexuberance. The designation “bubble” is reserved for the height of folly, but unfortunately, history is rich with folly. Throughout the long sweep of history, the bursting of an asset bubble has always been a financially traumatic event and has often precipitated social and political upheavals.

Because they are so culturally and financially painful, bubbles used to be separated by one or more generations because it took time to forget the experience. Bucking this convention, less than 10 years passed between the bursting of the dot-com bubble in 2000 and the housing bubble in 2006—a thoroughly unprecedented event—which calls into question the mindfulness of its participants. However, it is my contention that instead of these being two separate and distinct bubbles, they were merely subbubbles housed within a much larger and more profound credit bubble, which partially (but not entirely) excuses the all-too-close nature of their occurrences.

The Federal Reserve famously likes to claim that you can’t spot an asset bubble until it bursts. This is something of a mystery, because the definition of a bubble is pretty simple:

A bubble exists when asset prices rise beyond what incomes can sustain

. There is nothing especially tricky about that definition, and it provides an easy test that can be founded on solid data.

For example, when houses in Orange County, CA

1

rose to the point that the median house cost more than nine times the median income,

2

housing there was clearly in the grip of a bubble. A more normal ratio for housing would be in the range of roughly three times income, while anything over four times income really begins to stretch things a bit.

3

When you get to eight times income, you’ve been in a bubble for quite a while, it’s completely obvious even to casual observers, and it’s going to burst with predictable, economically painful results.

This seems pretty straightforward, but for some reason the Federal Reserve, under Greenspan and then Bernanke, continued to insist that bubbles couldn’t be spotted, and even if it

were

possible to spot them, that nothing should be done about them until after they burst. Greenspan and Bernanke hold to the view that it’s not the Federal Reserve’s job to spot or stop bubbles, only to ride to the rescue and help sweep up the debris after they burst. Given that the Fed is the principal source of the necessary credit and liquidity that are an absolute requirement of bubbles, this is a bit like firefighters claiming there’s no point in curbing arsonists’ behavior—that it is better to let them set fires so that they can then battle the blazes they’ve set. Lest you think this is a general defect of central banks and bankers, I should point out that New Zealand’s central bank takes the opposite view and sees it as their right and proper job to both spot bubbles early and nip them in the bud.

4

Bubble History

To better understand what bubbles are, how they form, and why they are economically painful, let’s take a look at a few historical examples, beginning with the tulip bulb craze in Holland in the 1630s.

In that period, a virus swept through the tulip farms and had the effect of creating beautiful and unique variants in tulip coloration that were transmissible to succeeding generations. Tulips were already an economically important crop for the country, so while it may seem strange to us now that a bubble could develop around flowers, tulips represented an important element of commerce to the people of Holland. Before long, incredible variants with brilliant streaks and accents were developed, and the more spectacular examples began trading at higher and higher amounts, building a speculative frenzy. Complicated trading routines built up around the products, and before long nearly all trades were conducted using credit.

At the height of the bubble, a single bulb of the most highly sought-after example, the Semper Augustus, which sported red petals and racy white streaks, commanded the same selling price as the finest house on the finest canal.

The tulip bubble could not have occurred were it not for the presence of ample credit. Credit is a necessary fuel for all bubbles; without it, no bubble can develop. After all, if the very definition of an asset bubble is that it grows “larger than incomes can sustain,” it means that funds to support the bubble’s growth have to come from somewhere besides current cash flows (i.e., current income). True to form, tulip-bulb trading soon outstripped the local money supply, and people began trading on credit.

Records indicate that the tulip craze ended even more suddenly than it began, crashing nearly to the bottom in a single day at the start of the new selling season in February of 1637. When bidding opened on that day, no buyers would bid, and prices rapidly cratered, never to recover. The people holding the last batches of purchased bulbs recorded major losses, creditors went bust, and an enormous amount of wealth evaporated, never to be seen again. Lives were ruined, fortunes were lost, and people promised themselves,

Never again

.

A second example of an early recorded bubble comes from the 1720s and is known as the South Sea Bubble. The South Sea Company was an English company granted a monopoly by the government to trade with South America under a treaty with Spain. The fact that the company was rather ordinary in its profits prior to the granting of the monopoly did not deter people from speculating wildly about its financial potential.

Even more startlingly, people were undeterred in snapping up shares of its stock, despite the fact that the company rather accurately billed itself as “A company for carrying out an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.” That’s about as clear a scam warning as an investor will ever receive, but bubbles have a way of shutting down critical thinking in the masses.

Sir Isaac Newton, when asked about the continually rising stock price of the South Sea Company, said that he “could not calculate the madness of people.” But then he, too, apparently went mad for company stock. He may have invented calculus and described universal gravitation, but he also ended up losing over 20,000 pounds,

5

a massive fortune in those days, to the burst South Sea Bubble, proving that even a truly rare intelligence can be outwitted by a bubble. For some reason, bubbles are extremely hard for most people to spot in advance. A bubble begins when people start relying on hope instead of reason, but a bubble really hits its stride when prudence is replaced by greed.

Bubble Characteristics

History is littered with the wreckage of financial bubbles involving a surprising diversity of assets, with more recent examples involving railroads, swamp land, Internet stocks, and housing. The asset itself, whether land or bulbs or pieces of paper, is irrelevant. What matters is having the right story—usually involving massive riches soon to come—a credulous mob, short-sighted (or greedy) lenders, and an ample supply of credit. If any one of these things is missing, no bubble will result.

What’s interesting is that nearly every bubble shares the same common, and therefore predictable, features. Bubbles are self-reinforcing, meaning that on the way up, higher prices become the justification for higher prices. Once the illusion is lifted, the game is suddenly and permanently over, but not instantly, as it takes time for reality to set in. This lends a rough symmetry to the price charts of assets as they rise and then fall over time. In the 1920s a bubble developed in U.S. stocks, and its bursting still echoes even today, because it was immediately followed by the Great Depression.

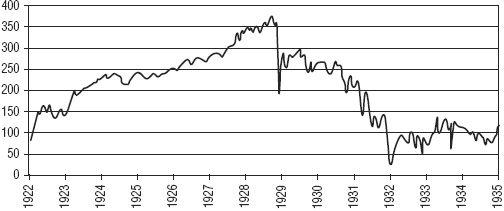

Figure 11.1

demonstrates two important traits about bubbles. Note that the amount of time it took the Dow Jones to run up to its price peak in 1929 is roughly the same amount of time that it took for prices to fall back to their starting levels. The first characteristic of bubbles is their rough symmetry. They first rise, and then they fall, but not instantly, revealing that bubbles take time to develop and then to unwind. First the psychology has to be built into a frenzy, a mob has to be formed, and then it has to be slowly dismantled, one person at a time. However, despite this apparent symmetry, bubbles usually burst just a little bit faster than they develop.

The second characteristic of bubbles that we see reflected in

Figure 11.1

is that asset prices will usually fully retrace to their starting point, if not just a little bit further. Whatever the starting point was for the asset prices in question is a reasonable place to suspect they’ll eventually end up at some point in the future.

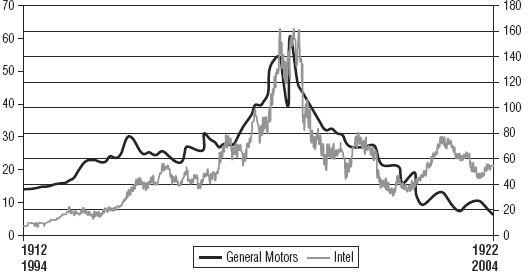

To reinforce this point,

Figure 11.2

shows the stock price of General Motors (in the black line) between the years 1912 and 1922 and Intel (in the shaded line) between 1992 and 2002, periods during which both stocks were swept up in bubbles. Here we might also note that the price data looks very similar for both stocks, despite the fact that one was a car company in the 1920s and the other was a high-tech chip manufacturer trading some 80 years later. Again we might note that they share the two characteristics of bubbles that we’ve already discussed: a rough symmetry in both time and price. They crescendo, then crash, and end up right where they began.