The Complete Yes Minister (25 page)

‘What about my quango abolition paper?’ he yelled, going red in the face.

‘Very good Frank,’ I said smoothly. ‘Imaginative. Ingenious.’

‘Novel,’ added Humphrey.

Then Frank announced that he wouldn’t let me suppress it. As if I would do such a thing! Me, suppress papers? I’m a democrat, a believer in open government. Frank must be raving mad.

‘I’ll get it to Cabinet through someone else,’ he threatened at the top of his not inconsiderable voice. ‘I’ll get it adopted as party policy. You’ll see.’

He marched to the door. Then he stopped, and turned. He had a beatific smile on his face. I didn’t like the look of it one bit. Whenever Frank smiles you know that something very nasty is about to happen. ‘The press,’ he said softly. ‘The press. If the press were to get hold of this . . .’

And suddenly, I had a brainwave. ‘Frank,’ I said gently, ‘I’ve been thinking. Changing the subject completely, of course, but have

you

ever thought about serving on a quango?’

you

ever thought about serving on a quango?’

‘Oh no,’ he replied, smiling his most unpleasant smile, ‘you’re not corrupting me!’

I explained patiently that nothing could be further from my thoughts. My idea is that, even better than abolishing the quango system, would be to make it work. And that if we set up a commission to supervise and report on the composition and activities of all quangos, it could be the answer. It could have very senior people, most Privy Councillors. I know that Frank has always secretly fancied himself hob-nobbing with Privy Councillors. I explained that such a body would need some really able people, people who have studied quangos, people who know the abuses of the system. ‘And in view of your knowledge, and concern,’ I finished, ‘Humphrey suggested your name.’

‘Privy Councillors?’ said Frank, hypnotised.

‘It’s up to you, of course,’ I added, ‘but it would be a great service to the public. How do you feel?’

‘You’re not going to change my opinions, you know,’ replied Frank thoughtfully. ‘There is such a thing as integrity.’

Humphrey and I both hastened to agree with Frank on the importance of integrity, and we pointed out that it was, in fact, his very integrity that would make him such a good member of this quango.

‘Mind you,’ Humphrey said, instinctively aware of Frank’s enormous sense of guilt which needs constant absolution and aware also of his deep commitment to the puritan work ethic, ‘it would be very hard work. I’m sure that service in this super-quango would involve a great deal of arduous foreign travel, to see how they manage these matters in other important government centres – Japan, Australia, California, the West Indies . . .’

‘Tahiti,’ I added helpfully.

‘Tahiti,’ agreed Sir Humphrey.

‘Yes,’ said Frank with an expression of acute suffering on his face, ‘it

would

be arduous, wouldn’t it?’

would

be arduous, wouldn’t it?’

‘

Very

arduous,’ we both said. Several times.

Very

arduous,’ we both said. Several times.

‘But serving the public’s what it’s all about, isn’t it?’ asked Frank hopefully.

Humphrey and I murmured, ‘serving the public, exactly’ once or twice.

Then Frank said, ‘And what about my quango paper?’

I told him it would be invaluable, and that he should take it with him.

And Humphrey offered to keep a copy on the files – with the Solihull Report.

1

In conversation with the Editors.

In conversation with the Editors.

2

The Crichel Down affair in 1954 was possibly the last example of a Minister accepting full responsibility for a scandal within his Department, about which he did not know and could not have known. Nevertheless, Sir Thomas Dugdale, then Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries, accepted that as the Minister he was constitutionally responsible to Parliament for the wrong actions of his officials, even though their actions were not ordered by him and would not have been approved by him. He resigned, was kicked upstairs to the Lords and a promising career came to an end. No Minister since then has been – depending on your point of view – either so scrupulous or so foolish.

The Crichel Down affair in 1954 was possibly the last example of a Minister accepting full responsibility for a scandal within his Department, about which he did not know and could not have known. Nevertheless, Sir Thomas Dugdale, then Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries, accepted that as the Minister he was constitutionally responsible to Parliament for the wrong actions of his officials, even though their actions were not ordered by him and would not have been approved by him. He resigned, was kicked upstairs to the Lords and a promising career came to an end. No Minister since then has been – depending on your point of view – either so scrupulous or so foolish.

8

The Compassionate Society

March 13th

Having effectively squashed the awful scandal that was brewing over the Solihull project, but having done a deal with Frank Weisel on the little matter of his suggested reforms in the quango system as a price for extricating myself from the appalling mess that Humphrey had got me into, I decided this weekend to consider my various options.

First of all it has become clear that Frank has to go. He really is very uncouth and, valuable as he was to me during my days in opposition, I can see that he lacks the subtlety, skill and discretion that my professional advisers display constantly.

[

The contradiction inherent in these two paragraphs indicates the state of mental confusion in which Hacker now found himself about Sir Humphrey after five months in Whitehall – Ed

.]

The contradiction inherent in these two paragraphs indicates the state of mental confusion in which Hacker now found himself about Sir Humphrey after five months in Whitehall – Ed

.]

However, having despatched the self-righteously incorruptible Frank the day before yesterday on his arduous fact-finding mission to review important centres of government – California, Jamaica, and Tahiti – I already feel a load off my mind as one significant source of pressure on me is lifted. I felt free and easy for the first time in months, as if I had actually gained time yesterday.

I am now able to draw some conclusions about the Civil Service in general and Sir Humphrey in particular. I begin to see that senior civil servants in the open structure

1

have, surprisingly enough, almost as brilliant minds as they themselves would claim to have. However, since there are virtually no goals or targets that can be achieved by a civil servant personally, his high IQ is usually devoted to the avoidance of error.

1

have, surprisingly enough, almost as brilliant minds as they themselves would claim to have. However, since there are virtually no goals or targets that can be achieved by a civil servant personally, his high IQ is usually devoted to the avoidance of error.

Civil servants are posted to new jobs every three years or so. This is supposed to gain them all-round experience on the way to the top. In practice, it merely ensures that they can never have any personal interest in achieving the success of a policy: a policy of any complexity takes longer than three years to see through from start to finish, so a civil servant either has to leave it before its passage is completed or he arrives on the scene long after it started. This also means you can never pin the blame for failure on any individual: the man in charge at the end will say it was started wrong, and the man in charge at the beginning will say it was finished wrong.

Curiously the Civil Service seem to approve of this system. They don’t like civil servants to become emotionally involved in the success or failure of policies. Policies are for Ministers. Ministers or Governments stand or fall by them. Civil servants see themselves as public-spirited impartial advisers attempting to implement, with total impartiality, whatever policy the Minister or the Government see fit.

Except that they

don’t

, do they? There’s the rub.

don’t

, do they? There’s the rub.

Because Permanent Secretaries are always trying to steer Ministers of all parties towards ‘the common ground’. [

In other words, the Department’s policy – a policy they have some hope of being able to pursue uninterrupted, whichever party is in power – Ed

.]

In other words, the Department’s policy – a policy they have some hope of being able to pursue uninterrupted, whichever party is in power – Ed

.]

Afterthought: considering that the avoidance of error is their main priority, it is surprising how many errors they make!

March 14th

Today, Sunday, has been spent going through my boxes and mugging up on my PQs [

Parliamentary Questions – Ed

.] for tomorrow.

Parliamentary Questions – Ed

.] for tomorrow.

I take PQs very seriously, as do all Ministers with any sense. Although the voters are mainly aware of a Minister’s activities through the newspapers and television, his real power and influence still stems from the House of Commons. A Minister cannot afford to make an idiot of himself in the House, and will not last long if he doesn’t learn to perform there adequately.

One day a month this ghastly event takes place. PQs are the modern equivalent of throwing the Christians to the lions, or the medieval ordeal by combat. One day a month I’m on First Order, and some other Minister from some other Department is on Second Order. Another day, vice versa. [

There’s also Third Order but no one knows what it’s there for because it’s never been reached – Ed

.]

There’s also Third Order but no one knows what it’s there for because it’s never been reached – Ed

.]

The Sundays and Mondays before I’m on First Order are absolute bloody anguish. I should think they’re anguish for the civil servants too. Bernard has an Assistant Private Secretary employed full-time on getting answers together for all possible supplementaries. Legions of civil servants sit around Whitehall exercising their feverish imaginations, trying to foretell what possible supplementaries could be coming from the backbenchers. Usually, of course, I can guess the political implications of a PQ better than my civil servants.

Then, when the gruesome moment arrives you stand up in the House, which is usually packed as it’s just after lunch and PQs are considered good clean fun because there’s always a chance that a Minister will humiliate himself.

Still, I’m reasonably relaxed this evening, secure in the knowledge that, as always, I am thoroughly prepared for Question Time tomorrow. One thing I’m proud of is that, no matter how Sir Humphrey makes rings round me in administrative matters,

2

I have always prided myself on my masterful control over the House.

2

I have always prided myself on my masterful control over the House.

March 15th

I can hardly believe it. PQs today were a disaster! A totally unforeseen catastrophe. Although I did manage to snatch a sort of Pyrrhic victory from the jaws of defeat. I came in bright and early and went over all the possible supplementaries – I thought! – and spent lunchtime being tested by Bernard.

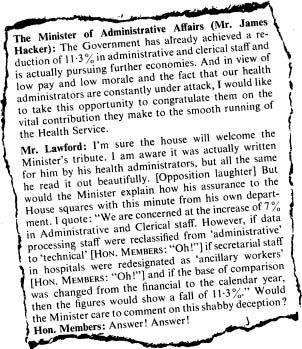

The first question was from Jim Lawford of Birmingham South-West who had asked me about the government’s pledge to reduce the number of administrators in the Health Service.

I gave the prepared reply, which was a little self-congratulatory – to the civil servants who wrote it, of course, not to me!

[

We have found the relevant exchange in Hansard, and reprint it below – Ed

.]

We have found the relevant exchange in Hansard, and reprint it below – Ed

.]

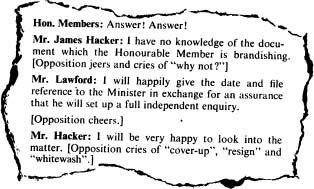

Somebody had leaked this wretched paper to Lawford. He was waving it about with a kind of wild glee, his fat face shining with excitement. Everyone was shouting for an answer. Humphrey – or somebody – had been up to his old tricks again, disguising an increase in the numbers of administrative and secretarial staff simply by calling them by some other name. But a rose by any other name is still a rose, as Wordsworth said. [

In fact, Shakespeare said ‘A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.’ But Hacker was an ex-journalist and Polytechnic Lecturer – Ed

.] This looked like it was going to be a real political stink. And a stink by any other name is still a stink. [

Or a stink by any other name would smell as bad? – Ed

.] Had it stayed secret, it would have been seen as a brilliant manoeuvre to pass off an increase of staff by 7% as a decrease of 11.3% – but when leaked, it suddenly comes into the category of a shabby deception. What’s more, an

unsuccessful

shabby deception – quite the worst kind!

In fact, Shakespeare said ‘A rose by any other name would smell as sweet.’ But Hacker was an ex-journalist and Polytechnic Lecturer – Ed

.] This looked like it was going to be a real political stink. And a stink by any other name is still a stink. [

Or a stink by any other name would smell as bad? – Ed

.] Had it stayed secret, it would have been seen as a brilliant manoeuvre to pass off an increase of staff by 7% as a decrease of 11.3% – but when leaked, it suddenly comes into the category of a shabby deception. What’s more, an

unsuccessful

shabby deception – quite the worst kind!

I stalled rather well in the circumstances:

Thank God one of my own backbenchers came to my rescue. Gerry Chandler asked me if I could reassure my friends that the enquiries would not be carried out by my own Department but by an independent investigator who would command the respect of the House. I was forced to say that I was happy to give that assurance.

So I just about satisfied the House on that one. However, I shall have to have a very serious talk about the whole matter with Humphrey and Bernard tomorrow. I don’t mind the deception, but allowing me to look ridiculous at Question Time is simply not on!

It’s not even in

their

interest – I wasn’t able to defend the Department, was I?

their

interest – I wasn’t able to defend the Department, was I?

March 16th

This morning started none too well, either.

Roy [

Hacker’s driver, and like all drivers, one of the best-informed men in Whitehall – Ed

.] picked me up as usual, at about 8.30. I asked him to drive me to the Ministry, as I was to spend all morning on Health Service administration.

Hacker’s driver, and like all drivers, one of the best-informed men in Whitehall – Ed

.] picked me up as usual, at about 8.30. I asked him to drive me to the Ministry, as I was to spend all morning on Health Service administration.

Other books

Once You'Ve Touched the Heart by Iris Bolling

The Mysterious Mannequin by Carolyn G. Keene

Kids of Kabul by Deborah Ellis

Sins of the Fathers by James Craig

Goal Line (The Dartmouth Cobras Book 7) by Sommerland, Bianca

The War (Play to Live: Book #6) by D. Rus

Swimming at Night: A Novel by Clarke, Lucy

Archangel Evolution by David Estes

0692321314 (S) by Simone Pond

El juego de los Vor by Lois McMaster Bujold