The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (65 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

During the early

Middle Ages

(ca 500â1100), imperial Rome in the west lay dormant as a distant memory under the mantle of Middle Age feudalism. The Romance languages grew up, and Latin remained operant only as an ecclesiastical language of worship and study. Here, Rome's legacy remained discernable only in the use of Latin, in the structure of church hierarchy, and in the beginning formation of canon law, which took its model (though not its source) from the Theodosian Code. Later, when

Justinian's works on civil law made it back into the west in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, ecclesiastical and civil law began to be studied and taught in a systematic fashion that was profoundly influenced by its Roman roots.

Â

When in Rome

The

Middle Ages

is the period between the fall of the Roman Empire in the west (470) and the beginning of the European Renaissance in the 1400s. This period is also known as

Medieval

(which also means “pertaining to the Middle Ages”). The “early” Middle Ages run approximately 500â1100, the “high” Middle Ages from 1100â1500.

Â

When in Rome

The term

Holy Roman Empire

refers to lands under the “Holy Roman Emperors” crowned by the pope. It had its beginnings in the crowning of Charlemagne (800) and then Otto I (962) as Roman Emperor. In spite of its beginnings with Charlemagne, the use of the name applies more to the twelfth century onward when the “Holy Roman Empire” was much more of a German phenomenon than French.

Still, the dream of universal political empire was there to be recalled. Although no military power would ever come again from Rome, a kind of central authority was developing in the increasing power of the papacy. When faced with Frankish power that was great enough to once again establish dominance over western Christendom (including Rome), an enterprising Pope Leo III turned the tables in 800 by legitimizing the Frankish empire as “Roman” and declaring victory. Thus were the beginnings of the

Holy Roman Empire.

Big

Caesar's Ghost! Charles the Great (Charlemagne)

The popes and eastern emperor had revived the title of Patrician for the Frankish kings, the title given to the military protector of the late western Roman Empire. This role was expanded by the greatest of the Carolingian monarchs, Charles the Great or Charlemagne (768â814). Charlemagne was an imposing figure (big, rough, and ruddy); he was also a remarkable general, administrator, and king. He united France, Germany, and Italy under his control by effective use of the Frankish army and by close cooperation with the church in Christianizing (by force when necessary) the Saxons.

Charlemagne came to Rome in 800 to see the holy sites and to settle the affairs of Pope Leo III, who was under attack from rival factions. At Christmas service, as he rose from prayer, the pope whipped out a crown, placed it on Charlemagne's head, and a well-rehearsed crowd proclaimed him emperor. Whether Charlemagne knew this Christmas present was coming or not is a matter of dispute. His court in Aachen had been talking about a “Christian Empire” previously, but Einhard, Charlemagne's biographer, said the king

was angered by the surprise coronation. What probably surprised him was the pope's bold move, which gave the impression that the pope crowned the emperor. This precedent served the pope's interests when future kings sought to establish their own authority and legitimacy against the papacy in the Investiture Controversy (see “The Holy Roman Empire” later in this chapter) of the eleventh through fourteenth centuries.

The eastern emperor first understood Charlemagne to be an underling, but Charlemagne saw himself as an equal “Augustus.” He had already begun construction of his capital at Aachen, which was called

Roma Secunda

(The Second Rome) and

Roma Ventura

(The Rome to Come) in direct contrast to Constantinople (

Nova Roma,

or New Rome). Charlemagne issued his own decrees, concluded alliances, and asserted imperial authority. Eventually, the east recognized Charlamagne.

Nova Roma

and

Roma Secunda

continued to claim the mantle of the old Rome, which had become an ecclesiastical center with the pope, the head of the “Holy Roman Republic” in central Italy.

The Carolingian Renaissance

Â

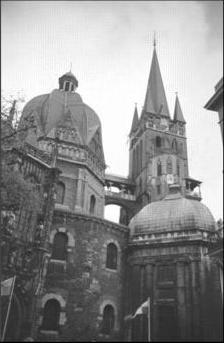

Roamin' the Romans

At Aachen (Aix la-Chapelle) in Germany, you can see the remains of

Roma Secunda.

Visit Charlemagne's unique octagonal cathedral and his chair, andâif you're there on one of the special festival daysâsome of the relics that he brought back from his coronation at Rome in 800.

Charlemagne wanted to reestablish Latin, whose use had nearly been forgotten except at the fringes of the Empire, particularly in the remote recesses of Britain and Ireland. Charlemagne ordered, in

De Litteris Colendis

(Concerning the Cultivation of Literary Studies), that Latin schools be set up at cathedrals and brought scholars, including Alcuin of York, to his court from all over the Empire to assist in reviving Latin education. Latin manuscripts were also sought out and recopied in the legible

Carolingian Miniscule

for study. This manuscript collection was crucial to the survival of Latin classical literatureânearly all that we have goes back to manuscripts copied in this period.

Â

When in Rome

One of the Carolingian Renaissance's great accomplishments was the development of a consistent, clear, and elegant style of lettering. This script, called

Carolingian Miniscule,

is the basis for modern typefaces. The serifsâthe little feet at the beginnings and endings of vertical lettersâimitate the beginnings and endings of hand-lettered strokes.

Charlamagne's octagonal cathedral (left portion) in Roma Secunda (Aachen, Germany).

The Holy Roman Empire

Â

Lend Me Your Ears

“We were seeing both proper sentiments and improper expressions in monastaries' compositions, which, though they tried, could not make clear what pious prayers the brethren were offering on our behalf. A neglect of learning had rendered pious devotion unable, in uneducated language, to express clearly in words without error what it was saying faithfully in the heart. And so we began to fear that this practical inability predicated less wisdom for understanding Holy Scripture than needs be. Errors of words are dangerous, errors of understanding more dangerous by far! And so do not neglect literary study but study diligently, with most humble and god-pleasing intent, so that you may fare well in penetrating the mysteries of the divine Scriptures.”âCharlemagne, from

De Litteris Colendis

Charlemagne's kingdom was split between his three sons. The middle kingdom ran along the Franco-German linguistic fault line, cutting a swath from the Netherlands to northern Italy between the vast regions on either side. I'm really tempted to say here that the continued splitting of Empires between sons is proof that people really don't learn anything from history. France and Germany have been at odds one way or the other over the territory of the middle kingdom ever since.

The mantle of “Emperor” was reinstated upon Otto I “the Great” (936â973) in 962. Otto established control of greater Germany and northern Italy. His empire, although it was made up largely of territory that never had been Roman, became known as the Holy Roman Empire in succeeding centuries. The Germanic emperors were chosen by the German nobility and confirmed (invested) by the pope. Disputes between emperors and popes as to who had ultimate authority became known as the Investiture Controversy. These tensions led not only to a sharper demarcation between church and state than either Islam or Byzantium, but to a climate that was ripe for Martin Luther's Reformation.