Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (62 page)

Â

And the East Goes On

In This Chapter

- The end of the eastern Roman Empire

- The beginning of Byzantine civilization

- Byzantine history in four Byzantine steps

- The fall of Byzantium and contributions to the West

The “fall” of the western Empire was not something that either the western or eastern Empires marked at the time. The making of Italy into a Germanic kingdom was not the decisive affair that it appeared in retrospect to Edward Gibbon (the famous writer of

The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

) in later days. In fact, the eastern Empire, the Orthodox Church (which included the bishop of Romeâthe popeâuntil 1054), and even nonorthodox sects continued on the idea that “Rome” was still functioning. Latin continued (for a time) to be the language of administration and of the army, and both emperors and patriarchs conceived of the Empire as still comprising the peoples, lands, and economies living within the bounds of Constantine the Great's day.

The east made one more heroic effort to reclaim this legacy under the emperor Justinian but was unable to maintain its gains. From that point, the divergent paths of east and west began to go their own ways. The east, compacted by pressure on all fronts, remained predominantly Greek in language and culture. The west spun out of the east's orbit toward Europe. The popes, unable to be protected by Constantinople, sought power and protection amid the tumultuous tribes and against the pressures of Islam in southern Sicily and Spain by allying themselves with the Frankish kings. This alliance spawned the birth of a new “Holy” Roman Empire, whose drive to reconquer the Empire for Christendom brought the crusades (see the next chapter) both to Constantinople and to Jerusalem.

A struggle for dominance in the orthodox church came to a head at this time as well, and the pope in Rome and the patriarch in Constantinople excommunicated each other in 1054. After this divorce, the western orthodox church became known as the “Roman Catholic” (Latin) Church, while the national eastern orthodox churches (Serbian, Greek, Armenian, Syrian, Russian, and so on) are usually clumped under the name “Eastern Orthodox.” Constantinople, as the center of what remained of the eastern Roman empire and the Eastern Orthodox Church, developed into the civilization we know as “Byzantium.” In this chapter we'll see how that civilization developed, flourished, and fell, giving back to the west a legacy that it had lost and largely forgotten.

Â

Roamin' the Romans

Istanbul is a wonderful, stewing city, piled with layers of history and culture and constantly mixing east and west at the crossroads of Europe and Asia. Spending time there means experiencing Byzantium,

Nova Roma,

Constantinople, and modern Istanbul all at once.

(Constantinople)

The opening of Constantine's new capital, Constantinople or

Nova Roma,

on the site of the ancient city of Byzantium turned out to be a stroke of genius. The city held a position that offered many advantages for the present and well into the future. It was easily defensible. It commanded access to the Black Sea and all of the rich trade routes to and from that area. It lay on the fault line between Asia and Europe facing the Greek, Oriental, Egyptian, and Barbarian quarters of the Empire like the hub at spokes of a wheel. It was an optimum place for a power base in the east.

The turbulent fifth century put the east through a tumultuous time of upheaval and both internal and external pressures. The Persians continued to press the Empire from the east, the Huns from the northeast, and the Goths from the northwest. The emperors kept these tribes at bay by a combination of military strength, defensive building, diplomacy, and a whole lot of tribute payments. These payments were bitterly resented by the wealthy from whom the money was extracted. Following the breakup of Atilla's empire after his death in 454, a people known as the Bulgars (hence Bulgaria) arose from its remnants and became a constant threat to Constantinople and its lands to the northwest.

Internally, the fifth through seventh centuries were dominated by struggles for central control of both political and religious matters by the capital, Constantinople. Doctrinal differences continued to plague the Christian ideal of unity, and regional conflicts often made these differences worse. Constantinople was not the definitive center of ecumenical power. Alexandria, Jerusalem, Antioch, and Rome all had powerful bishops who competed with each other for power, in establishing doctrine, and

for imperial favor. When the west was lost to the Germans and Islam conquered the other areas in the seventh century, Christianity in these cities became both politically and doctrinally isolated from the capital.

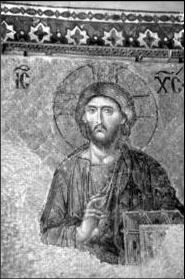

The primary doctrinal dispute of the early period continued to be the question of Christ's nature. Did Christ have two natures (human and divine) that existed independently in the same person or only one prevailing nature (the divine assimilating the human)? Bishops of Alexandria, such as Cyril, held one view, the bishops of Constantinople, such as Nestorius, the other. When it looked like Alexandria would become more powerful than Constantinople in determining doctrine, the emperor Marcian called the Council of Chalcedon in 451 to resolve the issue.

The early Christian Church wrestled with understanding the precise nature of Jesus, who gazes out from a mosaic in Justinian's church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (Istanbul).

What came of the Council of Chalcedon was the decision to adopt the opinion of the bishop of Rome (Pope Leo I), namely that Christ's human and divine natures were united within one person, but that they remained (in that one person) distinct and separate. This view (

hypostasis

) is still the dominant view in the west and Greek Orthodox Churches. However, the prevailing opinion of most of the eastern bishops andâinterestingly enoughâmost of the emperors of this period was that Christ's divine nature had absorbed the human and was one nature in one person, or

Monophysite

. Despite Chalcedon, this view remained predominant in Egypt and Syria.

Â

When in Rome

Hypostasis

is the condition wherein Christ's two natures (human and divine) remained separate and distinct in one person.Monophysitism

holds that Christ's two natures (human and divine) had become one (divine absorbing human) in one person.

Trouble continued between rival factions, including riots, lynchings, and forced resignations throughout the Empire. In 482, the emperor Zeno tried to bring some space for order by issuing a declaration of unity, called the

Henotikon.

While the

Henotikon

ratified the decisions of the councils that established, it also left some room for interpretation and debate for the Monophysites. What it called for, however, was a recognition of one catholic church whose decisions were orthodox and binding.

We've followed the emperors in the east up through Marcian (450â457), but here are two more influential emperors leading up to the reign of Justinian:

- Zeno

(474â491) came up with the idea of co-opting the troublesome Theodoric the Amal and using him against Odoacer in order to retake the west (see Chapter 18, “Barbarians at the Gates: The Fall of the Western Empire”). This deflected the Ostrogoths from Constantinople and relieved the Balkans of their pressure but led to the end of Italy as an independent province. Zeno tried to reestablish central control and authority over the doctrinal warring among Christians in the east by issuing the

Henotikon. - Anastasius

(491â518) was a Monophysite but was crowned only with a pledge to uphold orthodoxy and the

Henotikon.

He put down much of the political violence and intrigue of his day and worked to balance Monophysite and Chalcedonian interests in the appointment of bishops. Although his reign was marked by attacks from the Bulgars and Persians, he was nevertheless able to reform the Empire's finances and tax laws so that when he died he left an enormous surplus of gold in the treasury. Like most surpluses, however, it didn't last long.

Justinian (518â565)

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Justinian's reign is one of the best documented in Roman history. The historian Procopius witnessed much of Justinian's reign and published several works on its events. But Procopius was not a fan. After Justinian's death, Procopius published the

Secret History,

a libelous attack upon Justinian and his wife, Theodora. In Greek, this work is the

Anekdota,

the term from which we get

our

word “anecdotal” describing published but unconfirmed reportage.

Justinian was the nephew of Justin I, the Illyrian head of the imperial guard who succeeded Anastasius. He is the last

Roman

emperor and the first Byzantine. After him, the west was lost, the east became Byzantine, and the armies of Islam swept through the southern hemisphere of the old Rome. Justinian was intelligent, very well-educated, orthodox, and ambitious. His western roots probably only fueled his drive to reestablish the Roman Empire over both east and west.

Besides Justinian, the most powerful person in the Empire was the empress, Theodora, who was Justinian's wife, partner, and close councilor. Empress Theodora was the daughter of a bear keeper and may

have been a courtesan (a prostitute with a rich clientele) with a daughter before she met Justinian. Her background earned her the contempt of the upper class (Procopius reports all kinds of libel) and the tough mind-set of someone who came up from the streets. It was Theodora who told Justinian to have some backbone and convinced him to stay in the capital during the bleakest moments of the

Nika Rebellion.

The empress (perhaps because of her background) championed rights and protections for women, including buying impoverished women out of prostitution with her own money and setting up a foundation and home for them. Her influence with Justinian was profound even though she stayed independently powerful and sometimes (such as in her promotion of Monphysitism) opposed him. Justinian deeply mourned her death, by cancer, in 548.

Â

When in Rome

The Blue, Green, White, and Red

factiones

of the Constantinople chariot races became highly organized, powerful, and violent. These factions could threaten emperors and patriarchs with riots and demonstrations. When Justinian tried to clamp down on them both, Blues and Greens joined under the slogan of

Nika

(Conquer!) and attempted to drive him from power in 532. Their massive riots, called the

Nika Rebellion

, were nearly successful, but Theodora's determination, Justinian's strategy, and Belisarius's loyalty turned the tide at the last minute. The subsequent destruction of the factions' power firmly established (and perhaps motivated) Justinian's autocratic rule.

Justinian's greatest achievements were the outgrowth of his zeal for order, splendor, and control. His most enduring achievement was to cause Rome's historical law codes and judicial opinions to be ordered and codified. To these works, he added a manual for legal studies and a work of laws passed under his own administration. This monumental compilation of scholarship, the

Corpus Juris Civilis

(completed in 534), became the foundation for all canon law and most European civil law. His reforms of tax codes and administrative procedure and his attempts to reduce corruption also deserve commendation although they weren't always successful. His monumental building projects, best represented in the wonder of Hagia Sophia (dedicated in 537) in Constantinople and the churches of Ravenna, are breathtaking. Their wondrous mosaics, which utilized artistic trends developed from Persia, helped to develop the ethereal and otherworldly style associated with Byzantine art.

On the flip side, Justinian's autocratic nature led to the centralization of power and decisions in the person of the emperor. He attempted to systemize everything throughout the Empire

his

way with

him

at the controls. In addition, he insisted upon arcane ritual and pomp that made him a figure of mystery and awe. The centralization of power under him, including the elaborate court ceremony and etiquette, and the arcane knowledge needed to get anything done were in large part responsible for giving the term “Byzantine” its meaning today of something that is overly and purposefully complicated to the point of being incomprehensible to an outsider.