The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 (37 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

P

OVERTY

In the preta or hungry ghost realm one is preoccupied with the process of expanding, becoming rich, consuming. Fundamentally, you feel poor. You are unable to keep up the pretense of being what you would like to be. Whatever you have is used as proof of the validity of your pride, but it is never enough, there is always some sense of inadequacy.

The poverty mentality is traditionally symbolized by a hungry ghost who has a tiny mouth, the size of the eye of a needle, a thin neck and throat, skinny arms and legs, and a gigantic belly. His mouth and neck are too small to let enough food pass through them to fill his immense belly, so he is always hungry. And the struggle to satisfy his hunger is very painful since it is so hard to swallow what he eats. Food, of course, symbolizes anything you may want—friendship, wealth, clothes, sex, power, whatever.

Anything that appears in your life you regard as something to consume. If you see a beautiful autumn leaf falling, you regard it as your prey. You take it home or photograph it or paint a picture of it or write in your memoirs how beautiful it was. If you buy a bottle of Coke, it is exciting to hear the rattlings of the paper bag as you unpack it. The sound of the Coke spilling out of the bottle gives a delightful sense of thirst. Then you self-consciously taste it and swallow it. You have finally managed to consume it—such an achievement. It was fantastic; you brought the dream into reality. But after a while you become restless again and look for something else to consume.

You are constantly hungering for new entertainment—spiritual, intellectual, sensual, and so on. Intellectually you may feel inadequate and decide to pull up your socks by studying and listening to juicy, thoughtful answers, profound, mystical words. You consume one idea after another, trying to record them, trying to make them solid and real. Whenever you feel hunger, you open your notebook or scrapbook or a book of satisfying ideas. When you experience boredom or insomnia or depression, you open your books, read your notes and clippings and ponder over them, draw comfort from them. But this becomes repetitive at some point. You would like to re-meet your teachers or find new ones. And another journey to the restaurant or the supermarket or the delicatessen is not a bad idea. But sometimes you are prevented from taking the trip. You may not have enough money, your child gets sick, your parents are dying, you have business to attend to, and so on. You realize that when more obstacles come up, then that much more hunger arises in you. And the more you want, the more you realize what you cannot get, which is painful.

It is painful to be suspended in unfulfilled desire, continually searching for satisfaction. But even if you achieve your goal then there is the frustration of becoming stuffed, so full that one is insensitive to further stimuli. You try to hold on to your possession, to dwell on it, but after a while you become heavy and dumb, unable to appreciate anything. You wish you could be hungry again so you could fill yourself up again. Whether you satisfy a desire or suspend yourself in desire and continue to struggle, in either case you are inviting frustration.

A

NGER

The hell realm is pervaded by aggression. This aggression is based on such a perpetual condition of hatred that one begins to lose track of whom you are building your aggression toward as well as who is being aggressive toward you. There is a continual uncertainty and confusion. You have built up a whole environment of aggression to such a point that finally, even if you were to feel slightly cooler about your own anger and aggression, the environment around you would throw more aggression at you. It is like walking in hot weather; you might feel physically cooler for a while, but hot air is coming at you constantly so you cannot keep yourself cool for long.

The aggression of the hell realm does not seem to be your aggression, but it seems to permeate the whole space around you. There is a feeling of extreme stuffiness and claustrophobia. There is no space in which to breathe, no space in which to act, and life becomes overwhelming. The aggression is so intense that, if you were to kill someone to satisfy your aggression, you would achieve only a small degree of satisfaction. The aggression still lingers around you. Even if you were to try to kill yourself, you would find that the killer remains; so you would not have managed to murder yourself completely. There is a constant environment of aggression in which one never knows who is killing whom. It is like trying to eat yourself from the inside out. Having eaten yourself, the eater remains, and he must be eaten as well, and so on and so on. Each time the crocodile bites his own tail, he is nourished by it; the more he eats, the more he grows. There is no end to it.

You cannot really eliminate pain through aggression. The more you kill, the more you strengthen the killer who will create new things to be killed. The aggression grows until finally there is no space: the whole environment has been solidified. There are not even gaps in which to look back or do a double take. The whole space has become completely filled with aggression. It is outrageous. There is no opportunity to create a watcher to testify to your destruction, no one to give you a report. But at the same time the aggression grows. The more you destroy, the more you create.

Traditionally aggression is symbolized by the sky and earth radiating red fire. The earth turns into a red hot iron and space becomes an environment of flame and fire. There is no space to breathe any cool air or feel coldness. Whatever you see around you is hot, intense, extremely claustrophobic. The more you try to destroy your enemies or win over your opponents, the more you generate resistance, counteraggression bouncing back at you.

In the hell realm we throw out flames and radiations which are continually coming back to us. There is no room at all in which to experience any spaciousness or openness. Rather there is a constant effort, which can be very cunning, to close up all the space. The hell realm can only be created through your relationships with the outside world, whereas in the jealous god realm your own psychological hang-ups could be the material for creating the asura mentality. In the hell realm there is a constant situation of relationship; you are trying to play games with something and the attempt bounces back on you, constantly recreating extremely claustrophobic situations; so that finally there is no room in which to communicate at all.

At that point the only way to communicate is by trying to recreate your anger. You thought you had managed to win a war of one-upmanship, but finally you did not get a response from the other person; you one-upped him right out of existence. So you are faced only with your own aggression coming back at you and it manages to fill up all the space. One is left lonely once more, without excitement, so you seek another way of playing the game, again and again and again. You do not play for enjoyment, but because you do not feel protected nor secure enough. If you have no way to secure yourself, you feel bleak and cold, so you must rekindle the fire. In order to rekindle the fire you have to fight constantly to maintain yourself. One cannot help playing the game; one just finds oneself playing it, all the time.

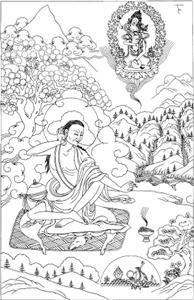

Milarepa with Vajrayogini above his head. Milarepa, one of the founding fathers of the Kagyü lineage, is renowned for having attained enlightenment in one lifetime. His life serves as an example of the approach of the yogi in Tibetan Buddhism, combining asceticism with devotion. Thus his followers are known as Kagyüpas, the practicing lineage. Above his head is Vajrayogini, who represents the feminine aspect of one’s innate nature and the clarity gained from discriminating awareness. The Vajrayogini principle plays an important role in the Kagyü tradition

.

DRAWING BY GLEN EDDY.

THREE

Sitting Meditation

T

HE

F

OOL

H

AVING UNDERSTOOD

about ego and neurosis, knowing the situation with which we are confronted, what do we do now? We have to relate with our mental gossip and our emotions simply and directly, without philosophy. We have to use the existing material, which is ego’s hang-ups and credentials and deceptions, as a starting point. Then we begin to realize that in order to do this we must actually use some kind of feeble credentials. Token credentials are necessary. Without them we cannot begin. So we practice meditation using simple techniques; the breath is our feeble credential. It is ironic: we were studying buddhadharma without credentials and now we find ourselves doing something fishy. We are doing the same thing we were criticizing. We feel uncomfortable and embarrassed about the whole thing. Is this another way to charlatanism, another egohood? Is this the same game? Is this teaching trying to make great fun of me, make me look stupid? We are very suspicious. That is fine. It is a sign that our intelligence is sharper. It is a good way to begin, but, nevertheless, finally, we have to do something. We must humble ourselves and acknowledge that despite our intellectual sophistication, our actual awareness of mind is primitive. We are on the kindergarten level, we do not know how to count to ten. So by sitting and meditating we acknowledge that we are fools, which is an extraordinarily powerful and necessary measure. We begin as fools. We sit and meditate. Once we begin to realize that we are actually one hundred percent fools for doing such a thing, then we begin to see how the techniques function as a crutch. We do not hang on to our crutch or regard it as having important mystical meaning. It is simply a tool which we use as long as we need it and then put aside.

We must be willing to be completely ordinary people, which means accepting ourselves as we are without trying to become greater, purer, more spiritual, more insightful. If we can accept our imperfections as they are, quite ordinarily, then we can use them as part of the path. But if we try to get rid of our imperfections, then they will be enemies, obstacles on the road to our “self-improvement.” And the same is true for the breath. If we can see it as it is, without trying to use it to improve ourselves, then it becomes a part of the path because we are no longer using it as the tool of our personal ambition.

S

IMPLICITY

Meditation practice is based on dropping dualistic fixation, dropping the struggle of good against bad. The attitude you bring to spirituality should be natural, ordinary, without ambition. Even if you are building good karma, you are still sowing further seeds of karma. So the point is to transcend the karmic process altogether. Transcend both good and bad karma.

There are many references in the tantric literature to mahasukha, the great joy, but the reason it is referred to as the great joy is because it transcends both hope and fear, pain and pleasure. Joy here is not pleasurable in the ordinary sense, but it is an ultimate and fundamental sense of freedom, a sense of humor, the ability to see the ironical aspect of the game of ego, the playing of polarities. If one is able to see ego from an aerial point of view, then one is able to see its humorous quality. Therefore the attitude one brings to meditation practice should be very simple, not based upon trying to collect pleasure or avoid pain. Rather meditation is a natural process, working on the material of pain and pleasure as the path.

You do not try to use meditation techniques—prayer, mantra, visualization, rituals, breathing techniques—to create pleasure or to confirm your existence. You do not try to separate yourself from the technique, but you try to become the technique so that there is a sense of nonduality. Technique is a way of imitating the style of nonduality. In the beginning a person uses technique as a kind of game because he is still imagining that he is meditating. But the techniques—physical feeling, sensations, and breathing, for instance—are very earthy and tend to ground a person. And the proper attitude toward technique is not to regard it as magical, a miracle or profound ceremony of some kind, but just see it as a simple process, extremely simple. The simpler the technique, the less the danger of sidetracks because you are not feeding yourself with all sorts of fascinating, seductive hopes and fears.

In the beginning the practice of meditation is just dealing with the basic neurosis of mind, the confused relationship between yourself and projections, your relationship to thoughts. When a person is able to see the simplicity of the technique without any special attitude toward it, then he is able to relate himself with his thought pattern as well. He begins to see thoughts as simple phenomena, no matter whether they are pious thoughts or evil thoughts, domestic thoughts, whatever they may be. One does not relate to them as belonging to a particular category, as being good or bad; just see them as simple thoughts. When you relate to thoughts obsessively, then you are actually feeding them because thoughts need your attention to survive. Once you begin to pay attention to them and categorize them, then they become very powerful. You are feeding them energy because you have not seen them as simple phenomena. If one tries to quiet them down, that is another way of feeding them. So meditation in the beginning is not an attempt to achieve happiness, nor is it the attempt to achieve mental calm or peace, though they could be by-products of meditation. Meditation should not be regarded as a vacation from irritation.