The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five (14 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

There is this rare preciousness of our human life: we each have our brain, our sense perceptions, our materials to work on. We have each had our problems in the past: our depressions, our moments of insanity, our struggles—all these make sense. So the journey goes on, the accident goes on—which is that we are here. This is the kind of romanticism, the kind of warmth I am talking about. It is worthwhile approaching the teaching in this way. If we do not, we cannot relate with the Padmasambhava principle.

Student:

Could you tell us something about how you related to the crazy wisdom of your guru, Jamgön Kongtrül of Sechen, if he had it, and how you combined those two approaches of wealth and poverty when you studied with him?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

I think my way of working with it was very similar to everyone else’s. At the beginning, personally, I had a lot of fascination and admiration based on the poverty point of view. Also, it was very exciting, because seeing Jamgön Kongtrül Rinpoche rather than just having to sit and memorize texts provided quite a break. It was always fun to watch him, and to hang out with him was great.

This was still based on a poverty-stricken kind of mentality—on being entertained by that which you do not have. All I had were my books to read and my tutor to discipline me. Moreover, Jamgön Kongtrül, with his extraordinary understanding and spiritual energy, was presented as the example of what I should become when I grew up. This is what I was told over and over again, which was based on the style of poverty and materialism. Of course, the people in the monastery cared for me, but they were also concerned with public relations: fame, glory, enlightenment.

But as I became close to Jamgön Kongtrül, I gradually stopped trying to collect something for myself so that I could be enriched. I began just to enjoy his presence, just to go along with him. Then I could really feel his warmth and his richness and be part of it as well. So it seems that you start with the materialistic approach and gradually change to the sane approach, to devotion.

As far as Jamgön Kongtrül is concerned, he possessed all the qualities of Padmasambhava. Sometimes he looked just like a big baby. That was the little prince aspect. Sometimes he was kind and helpful. Sometimes he put out black air that gave you the feeling that something was wrong and made you feel extraordinarily paranoid. I used to feel like I had a huge head hanging out and was very embarrassed about it, but I didn’t know what to do.

Student:

Is the cynical phase that we have been going through due to our being Americans? Does it have something to do with American culture, or has it got to do with something about the teachings that is independent of culture?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

I think it is both. It is because of American culture, especially because of this particular period of social change in which a spiritual supermarket has developed. So we have to be smart to beat the supermarket mentality, to not be sucked in by it.

On the other hand, it is also a very Buddhistic approach. You can imagine finding this kind of mentality at Nalanda University. Naropa and all the other pandits were cutting through everything with their superlogical minds. It was quite awesome. This approach is connected with the Buddhist idea that the teachings began with pain and suffering. This is the first noble truth. It is a realistic way of looking at things. It is not enough just to be simple-minded and malleable; some weight is needed; some cynicism. Then, by the time you get to talking about the path, which is the fourth noble truth, you have the sense of something positive coming out, which is the devotional part coming through.

So it is a combination of cultural and inherent factors. Still, that is the way it ought to begin. And it does begin that way.

Student:

You used the word

accident.

In your view, does that include free will?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

Well, it’s both; that is, free will is the cause of the accident. Without free will, you can’t have accident.

Student:

We have been talking about Padmasambhava’s way of relating to confused people. Do you think it’s appropriate to take the viewpoint of Padmasambhava in relating to ourselves; for example, should we let the neurosis flood in and things like that?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

I think that is the whole point, yes. There is a Padmasambhava aspect in us. There are certain tendencies not to accept our existing confusion and to want to cut through it. There is something in us that says we are not subject to the confusion, a revolutionary aspect.

Student:

Is it important to try to avoid cynicism now in our approach to the teachings?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

I think the cynicism remains continuous and becomes powerful cynicism. You cannot just switch it on and off like changing television channels. It has to continue, and it should be there. For instance, when you encounter a new or further level of teaching, you should test it out in the same way as you have been doing. Then you will have more information and your eventual trust in it will have more backbone.

Student:

Does Padmasambhava’s teaching remain up-to-date? Don’t historical and cultural changes require changes in the teaching?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

It remains up-to-date because it is based on relating with confusion. Our confusion remains up-to-date, otherwise it would not confuse us. And the realization of confusion also remains up-to-date, because confusion causes our question and prompts us to wake up. The realization of the confusion is the teaching, so it is a constantly living situation, constantly lived-in and always applicable.

Student:

You spoke earlier about Padmasambhava being in a state of decisionlessness. Is that the same thing as not thinking at all? You know—the mind just functioning?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

Which is thinking. But you

can

think without thinking. There is a certain kind of intelligence connected with the totality that is more precise, but it is not verbal; it is not conceptualized at all. It does think in some sense, but it is not thinking in the ordinary sense.

S:

Is it thinking without scheming?

TR:

Something more than that. It

is

thinking without scheming, but it is still something more than that. It is a self-existing intelligence of its own.

Student:

Rinpoche, about devotion. I can become so joyous when I experience the dharma’s living quality. There’s such great joy; it’s like being high. But then I find a fall can follow this experience, which brings me down to a sort of barren land or desolate country. I’ve been feeling it’s better to avoid these extreme feelings, because they seem always to bring their opposite.

Trungpa Rinpoche:

You see, if your approach is a poverty approach, then it is like begging for food. You’re given food and you enjoy it while you’re eating it. But then you have to beg again, and between the two beggings there is a very undesirable state. It’s that kind of thing. It’s still relating to the dharma as the “other,” rather than feeling that you have it. Once you realize that the dharma is you and you are in it already, you don’t feel particularly joyous. There is no extra bliss or any high of any kind at all. If you are high, then you are high all the time, so there is no reference point for comparison. And if you are not high, then you are extraordinarily ordinary.

Student:

Doesn’t your idea of accident contradict the law of karma, which is that everything has a cause and effect?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

Accident is karma. Karmic situations take place by way of accident. It works like flint and steel coming together and causing a spark. Events come unexpectedly. Any event is always a sudden event, but it is a karmic one. The original idea of karma is the evolutionary action of the twelve nidanas, which begins with ignorance, with the potter’s wheel. That evolutionary action that begins with ignorance is an accident.

S:

The ignorance itself is the accident?

TR:

Ignorance itself is the accident. Duality itself is the accident. It is a big misunderstanding.

CRAZY WISDOM SEMINAR II

Karmê Chöling, 1972

ONE

Padmasambhava and the Energy of Tantra

I

N THIS SEMINAR,

we will be studying Tibet’s great Buddhist saint Padmasambhava. Padmasambhava was the great Indian yogi and vidyadhara who introduced the complete teachings of buddhadharma to Tibet, including the vajrayana, or tantra. As to the dates and historical details, we are uncertain. Padmasambhava is supposed to have been born twelve years after the death of the Buddha. He continued to live and went to Tibet in the eighth century to propagate the buddhadharma there. Our approach here, as far as chronology and such things are concerned, is entirely unscholastic. For those of you who are concerned with dates and other such historical facts and figures, I am afraid I will be unable to furnish accurate data. Nevertheless, the inspiration of Padmasambhava, however old or young he may be, goes on.

Rather than studying the life and acts of Padmasambhava according to a chronological-historical description, we will be trying to discuss the fundamental meaning of Padmasambhava-ism, if you wish to call it that—the basic qualities of Padmasambhava’s existence as they are connected with the dawn of the vajrayana teachings in Tibet. We might call this the Padmasambhava principle. The Padmasambhava principle opened the minds of millions of people in Tibet and is already opening people’s minds in this country—and in the rest of the world for that matter.

Padmasambhava’s function in Tibet was to bring forth the teachings of the Buddha by relating with the Tibetan barbarians. The Tibetans of those times believed in a self and a higher authority outside the self, which is known as God. Padmasambhava’s function was to destroy those beliefs. His approach was if there is no belief in the self, then there is no belief in God—a purely nontheistic approach, I am afraid. He had to destroy those nonexistent sand castles that we build. So the significance of Padmasambhava is connected with the destruction of those delusive beliefs. His entry into Tibet meant the destruction of the delusive theistic spiritual structures that had been established in that country. Padmasambhava came to Tibet and introduced Buddhism. In the course of introducing it, he discovered that he not only had to destroy people’s primitive beliefs, but he also had to raise their consciousness at the same time. So in introducing the Padmasambhava principle here, we must also relate with the same basic problems of destroying what has to be destroyed and cultivating what has to be cultivated.

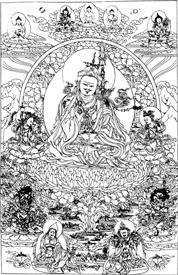

Pema Jungne (Padmasambhava)

.

To begin with, we have to destroy certain fallacious notions connected with holiness, spirituality, goodness, heaven, godhood, and so forth. What makes these fallacious is the belief in a self, ego. That belief makes it so that “I” am practicing goodness; thus, goodness is separated from “me”; or it implies some kind of a relationship in which goodness depends on “me” and “me” depends on goodness. Thus, fundamentally [since neither exists on its own], there is nothing there to build on at all. With this ego approach, a conclusion is drawn because of “other” factors that prove that the conclusion is so. From that point of view, we are building sand castles or building castles on an ice block.

According to the Buddhist outlook, ego (or self) is nonexistent. It is not founded on any definite, real factors at all. It is based purely on the belief or assumption that since I call myself so-and-so, therefore I exist. And if I do not know what I am called, what my name is, then there is no structure there on which the whole thing is based. The way this primitive belief works is that believing in “that,” the other, brings “this,” the self. If “that” exists, then “this” must also exist. I believe in “that” because I need a reference point for my own existence, for “this.”

In the tantric, or vajrayana, approach introduced into Tibet by Padmasambhava, my existence in relationship with others who exist is based on some energy. It is founded on some sense of understanding, which could also equally well be some sense of misunderstanding.

When we ask ourselves, “Who are you, what are you?” and we answer, “I am so-and-so,” our affirmation or confirmation is based on putting something into that empty question. A question is like a container that we put something into to make it an appropriate and valid container. There is some energy that is there between the two processes of giving birth to a question and producing an answer, an energy process that develops at the same time. The energy that develops between the question and the answer is connected either with complete truth or complete falsehood. Strangely enough, those two do not contradict each other. Complete truth and complete falsehood are in some sense the same thing. They make sense simultaneously. Truth is false, falsehood is true. And that kind of energy, which goes on continuously, is called tantra. Because it does not matter here about logical problems of truth or falsehood, the state of mind connected with this is called crazy wisdom.