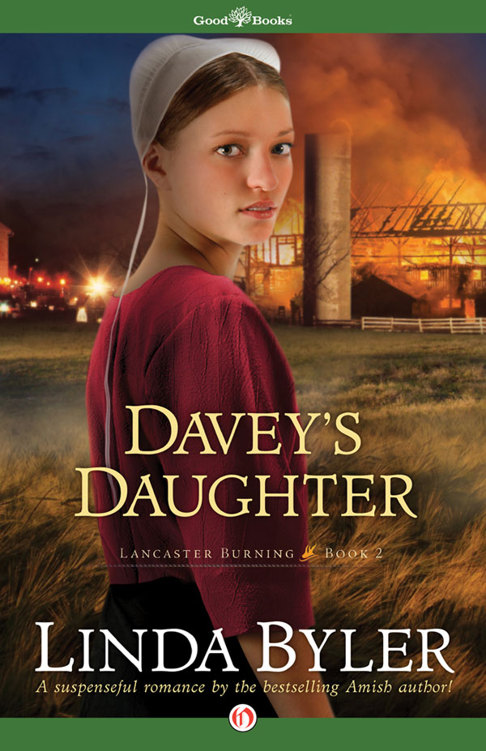

Davey's Daughter

Lancaster Burning • Book 2

Lancaster Burning • Book 2

S

arah Beiler, Davey’s daughter, bent over, grabbed the back of the stubborn boot, and yanked as hard as she could. She groaned and threw the offensive footgear into a corner of the

kesslehaus

(wash house). Priscilla had worn them again and gotten them wet. Would she never learn?

Resigned now, Sarah found her old Nikes, undid the laces, shoved her feet into them, and tied them again

—

more roughly than necessary. She’d just have to tiptoe through the snow, unless Dat had shoveled a path to the barn, which was unlikely considering how precise he was with the milking time.

Grabbing a navy blue sweatshirt, she pulled it over her head, tied a men’s handkerchief low on her forehead, and plunged through the door, bracing herself for the cold and snow of December.

Sarah quickly lowered her head to avoid the stinging flakes, then lifted her face to the sky, which was dark and gray but alive with the swirling whiteness of the first snowstorm of the year. Christmas was only a week away.

They’d have a white Christmas!

Already, the snow was drifted against the corner wall of the new cow stable, where the wind created eddies, same as a creek when it rounded a bend.

Excitement pulsed in her veins at the thought of an early snowstorm creating a wonderland for Christmas. It was just more festive with snow. Holly was greener, berries were redder, cookies more Christmasy, gifts wrapped in red and green glowed brighter when there was sparkling snow.

Sarah’s early morning grumpiness had dissipated by the time she pulled on the door latch to the milk house, where the glass steamed from the hot water Dat had already used. She entered and set to work assembling the gleaming stainless steel milking machines.

The diesel in the shanty purred to life as Dat prepared to begin the milking.

When Sarah walked into the newly whitewashed cow stable, the two rows of clean black and white Holsteins were already being fed, jostling their chains, lifting and lowering their heads, impatient to taste the richness of their twice daily portion.

“Good morning, Sarah.”

“Morning.”

Dat went on with his feeding as Sarah prepared the first three cows for the milking machines and then turned to fetch them from the milk house.

She still appreciated the barn, the cow stable, and the milk house in a way she never had before their barn burned to the ground only eight months prior. It had happened one April night when the buds were bursting open on the maple trees in the front yard.

The whole family had suffered a night of terror, standing by helplessly as innocent animals, family pets, faithful workhorses, and driving horses had suffered horrible deaths. The battle against real fear occurred after the local police called it arson.

Davey, as a minister of the Old Order Amish who had lost his own barn, could freely sympathize with Ben Zook and Reuben Kauffman after each of their barns was also set on fire. He became a pillar of support for both of them.

His leadership in the community was thrown into question, however, when Priscilla, his daughter who had been deeply traumatized by the terrible, fiery death of her riding horse, Dutch, was questioned by a local reporter about the fires. She answered the reporter in a way that was considered inappropriate for the Amish, saying she hoped the arsonist would go to jail and die there.

Levi was the oldest of Davey’s children and had Down syndrome. He was thirty-one years old, overweight, and clumsy, but he was the character of the family and was known and loved by everyone around him. He enjoyed a life of love and compassion, feeling pretty sure that he was an important part of Lancaster County, especially since the last meeting between prominent members of the church, when he was called upon to describe what he had seen the night of the Beiler barn fire as he had been up and about the house with a sore throat.

Levi had an exceptional memory and was astonishingly observant. He had informed the men at the meeting that a white car, maybe a Volkswagen, had driven by the house.

Sarah was now twenty years old, tall and lithe, with curly hair that never lay as sleekly as she wanted. Her seawater green eyes changed color with her emotions

—

gray and stormy like waves tossed by the wind when she was upset, dancing yellow lights like sunshine on rippling water when she was happy. She had grown up with a constant yearning for her neighbor, Matthew Stoltzfus, whose brown eyes never failed to melt her. He had always been the object of her affection, and she had never dreamed of marrying anyone but him. But when she turned sixteen years old, the time when she entered her years of

rumspringa

(running around), Matthew suddenly began dating her friend, Rose, a sweet and beautiful girl.

Their relationship had thrown Sarah completely off balance and stretched her faith to its limit. Now suddenly, a few years after they had begun dating, Rose called off the relationship with Matthew, which put him in an awkward situation as he strove to hide his emotions with pride and hurt battling for control. He had given Sarah enough reason to believe that he would now pursue her, and she now lived in constant suspense waiting to see what would really happen.

“Sarah!”

“What?”

Dat’s call was urgent, so Sarah set down the milker she was carrying and hurried toward the sound of his voice.

“Is Priscilla up yet?”

“No.”

She came upon an unforgettable sight. In the early morning dimness, the sputtering gas lantern swayed on its hook from the new, yellow post that had been erected by hundreds of men eager to show their charity by helping Davey back to his feet, lifting his spirits to new heights by erecting a new barn in only a few days. In the lantern’s light, Dat’s eyes were pools of shadow, the wide, black brim of his felt hat hiding the emotion on his face as he stood, helpless, in the face of the scene before him.

Sarah reached her father and grasped at the oak post, rough and splintered but a support as she beheld the horror. She let go of it then as both hands went to her mouth, and she uttered a long moan of denial.

In the light of the unforgiving lantern lay Priscilla’s new riding horse, also named Dutch, a replacement for her first beloved horse. Dat had tied him in the stall with a neck rope

—

the soft, sturdy nylon rope often used for driving horses

—

when he was cleaning the box stall the day before.

Dat had intended to finish, but a distraught member of the church had come to seek advice, and Dat left the barn. He figured Dutch would be alright for a while. Then, with his mind filled with his church member’s troubles, he had spent a distracted evening and hadn’t been able fall into a restless sleep until after midnight.

Now Dutch’s sides bulged, and his legs curled helplessly. But the real horror was his twisted, elongated neck, where the rope buried into his flowing mane, strangling the life from his veins as he had desperately struggled to free himself. It appeared as though his own panic had been the cause of his death.

“He’s dead!” Sarah cried, her voice cracked with fear. Dat shook his head, his lips a grim line of resolve, but he did not utter a word. Slowly, he reached into his pocket, extracted his old Barlow knife, moved in beside the already cold form, and cut the nylon rope with a few precisely executed movements.

Dutch’s head flopped to the floor with a “whumpf,” and bits of shavings wafted upward, clung to the beautiful mane, and shuddered, as if attempting to give some sort of life back to the dead horse.

Dat did not look at Sarah, his voice like gravel pouring over stone when he said, “Go get her.”

“I can’t.”

Dat was suddenly crushed by the emotional weight of too many barn fires, too many men bringing their petty disagreements, too many sleepless nights. He turned on Sarah, his large, work-roughened hands clenched, his eyes bulging, and he yelled in a voice Sarah had never heard before.

“

Harich mich

(Listen to me)!”

Her breath coming in harsh sobs, Sarah ran, slipping and falling to her knees, her bare skin exposed to the wet iciness of the snow. She got to her feet and kept going, blindly. She slipped again on the wet floorboards of the porch, righted herself, and fell through the door, her breath coming in ragged gasps.

Mam was sorting laundry on the floor of the

kesslehaus

. The safe, ordinary odor of moist, used towels, soiled socks and dresses and shirts and aprons brought Sarah back from the shock. Her mother straightened, looking at her in surprise.

“Sarah!

Voss iss lets

(What is wrong)?”

“Mam! Priscilla’s horse! He…he hung himself.”

“Oh my,” Mam replied with complete hopelessness, a defeat so raw she could not utter another word, unable to draw the breath needed to say anything more.

Leaving her mother, Sarah moved heavily, numbly, up the stairs and found her way to her younger sister, Priscilla, who lay snugly under the warm comforters, sweet and innocent. Her hair was light brown with streaks of blonde running through it, and her green eyes were closed in trusting slumber.

Sarah reached out and shook her shoulder, then sat on the edge of the bed and whispered, “Priscilla. Cilla!”

Alarmed, Priscilla sat up quickly, her large eyes blinking.

“Sarah! It’s your turn to milk.”

“I am milking. Priscilla, listen, you have to be strong. Dutch…he…your horse is dead.”

“What?”

It was plain she had not understood Sarah’s words. She was sure she just hadn’t heard right.

“He hung himself by his neck rope.”

“No, he didn’t. He couldn’t have. He’s not in a tie stall.”

Priscilla was certain there was a mistake, so there was no reason for her to become upset. She remained calm and carefully explained it all away in her still somewhat groggy state.

Sarah persuaded her to get dressed and come to the barn, where they found Dat, grimly lifting full, heavy milkers and dumping them into the stainless steel Sputnik vat on wheels. Wearily, as if he had suddenly aged far beyond his years, he told his daughter what had happened, flinching in the face of her inability to accept what had occurred.

“He’ll be alright,” she said and moved away toward the horse stables to find her beloved pet, still and cold and unmoving, her second precious horse now as dead as her first.

“He did,” she whispered.

Broken, she fell on her knees beside him, her hands fluttering to his chest, reaching out to feel for just one steady heartbeat but defeated already.

“Why?”

She lifted her head, seeking an explanation.

Dat spoke reassuringly, taking all the blame, saying he should not have left him in a tie stall.

“But why?” Priscilla asked, struggling to understand how a horse as smart as Dutch could have panicked as the rope tightened.

“Well, it happens. Some horses just lose all common sense and keep jerking and pulling until their breath leaves them.”

Priscilla remained quiet, her hands stroking the still, lifeless form of her horse. She was weeping but calmly, resignedly.

Sarah searched Dat’s face, and he shrugged his shoulders.

“I’ll finish milking,” Sarah said.

Dat nodded, then looked past her as the figure of his wife came through the door. He was visibly lifted by the appearance of his unfailing supporter.

Mam did not go to Priscilla. She just put a hand on the side of the cow that was being milked and took over, instinctively handling the heavy milking machines and helping Sarah do what had to be done.

They left Dat with Priscilla and Dutch.

The cold and the snow whirled outside the rectangular blocks of yellow light at the windows. The purring of the diesel was muffled by the storm and the drifting snow as the milkers ka-chugged along, extracting the rich milk from the cows.

There was no singing, no humming, no whistling this morning. There were only two women who had once more been assailed by adversity and were now gathering the strength and resolve they would need yet again. They silently went about their duties, knowing that this, too, would pass, and the sun would shine again, for Priscilla, for them all.

In the horse barn, Dat stood, his head bent. Then he fell to his knees beside Priscilla, an arm going around her thin, heaving shoulders.

That was all.

But is there greater human support than that of a father’s love? Feeling the undeniable strength of that strong arm across her back, a heart filled with compassion and caring propelling it, Priscilla turned her head and buried it in her father’s coat as his other arm came around and held her close to his heart. He willed her to be strong, to be able to rise above this loss one more time.

“

Noch ay mol

(One more time), Priscilla,” he murmured, his tone as cracked and broken as his heart.

Priscilla nodded and sniffed but remained in the circle of her father’s comforting arms.

“God does chasten those He loves. Don’t feel as if you did something bad to deserve this. You didn’t. Perhaps He just allowed this to see what we make of it.”

Sighing, he reached for his handkerchief, stood up, and handed it to her.