The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War (39 page)

Read The Coldest Winter: America and the Korean War Online

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #War

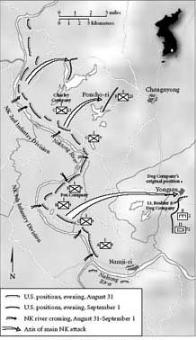

Stryker’s estimates jibed with the memories of Master Sergeant Graham, who was in charge of Charley Company’s Second Platoon with a mortar section and a recoilless rifle section, and with that of Master Sergeant Erwin Ehler, who was in charge of Fourth Platoon, which was a heavy weapons platoon. Graham’s platoon was in the center of the Charley Company position. To the left of it was Ehler with the Fourth Platoon and to the right of Graham was B Company of their battalion. To the left of Ehler and his platoon was the road to Changnyong, and then troops from the Ninth Infantry Regiment, also part of the Second Division. The gaps in the line were terrible. “We were so far from each other that we didn’t know where the hell anyone else was,” remembered Ehler, who was badly wounded that night. Graham’s Second Platoon had a front of about two thousand yards. On Graham’s right was a gap of about two thousand yards, and after that, the position of B Company, also part of the First Battalion, began. “We could,” Sergeant Graham later wrote, “cover the gaps [between us] by fire during the day, but it was impossible at night.”

That they were pathetically thin on that line no one knew better than Captain Cyril Bartholdi, the Charley Company commander. He was an experienced officer and distantly related to the man who had designed the Statue of Liberty; he had commanded troops in World War II and was very much aware of the vulnerability of his men at this point, that there was no way they would be able to stop the kind of North Korean push everyone was expecting. They were, he understood, part of a fragile little trip wire, there primarily to help warn the rest of the Eighth Army. Their job would be to signal the North Korean attack, slow it down slightly if at all possible, report on its size, and hope that the men back at some distant headquarters might eventually be able to bring enough troops and firepower up to check the attack. The cruelty of their assignment, he understood, might mean that they all were going to die there.

8. T

HE

N

AKTONG

B

ULGE,

A

UGUST

3

1–SEPTEMBER

1

,

1950

On the afternoon of August 31, the men in the varying units of the Twenty-third Regiment, including Charley Company, had noticed enemy troops assembling on the other side of the Naktong, and in some places even building rafts. The attack was clearly coming soon—in fact, it appeared to be, they thought, virtually under way. The Naktong might be a valuable defensive line, but it was an imperfect one. The North Koreans were known to slip out at night and create what were essentially hidden underwater bridges by putting sandbags on the bottom, invisible to the naked eye because of the muddy quality of the water. Then, when the battle began, their men and their vehicles had a way to cross more easily, and there were fears among some of the Americans, as they waited for the strike, that such a bridge might already be in place.

The first In Min Gun strike was aimed at Baker Company. At 8:30

P.M.

, Lieutenant William Glasgow of Baker Company reported a bizarre sight, what seemed like countless enemy soldiers holding torches and moving toward the river, the torches spelling out, he reported, the letters V and O. No one ever figured out what the letters meant (if they actually were letters)—perhaps they were primitive directional signals meant to guide different units to the right sector. The North Korean prisoners the Americans eventually took were of little help on this matter. The most that the Americans were eventually able to get from them was that the North Koreans, who were still very confident, expected to reach Pusan in three days.

Then the Communist artillery barrage began. Suddenly, the Americans witnessed a terrifying sight, North Korean troops as far as the eye could see, coming up to the river and crossing it. Within the first fifteen minutes, Charley Company observers estimated that at least thirteen hundred North Korean troops had crossed the Naktong. In the Baker Company sector, it was later estimated, there were four separate crossings of about a battalion each, totaling about a division.

There was a comparable assault on the Charley Company sector. “Like

millions of ants crossing the river and coming at us when we first saw them,” said Terry McDaniel, a supply sergeant who was there that night. To the Americans, so isolated, so outnumbered, waiting fatefully in their positions, it was a frightening spectacle, a fighting force for which they had great respect, coming at them in such numbers. The initial wave of North Koreans took terrible casualties. “At first they had presented a great target,” recalled Rusty Davidson, a company clerk pressed into frontline service because everyone was being pressed into frontline service, “and someone in our platoon had shouted out that it was going to be a turkey shoot, but then there were so many of them, and so few of us, that we soon realized we were the turkeys.”

Back at the battalion command post they had expected to be hit, but not this hard or on a battlefield none of them would have chosen. Unfortunately, it was not about choice. If there had been any element of choice, they would have had several other divisions there to share the sector, and Air Force planes overhead to welcome the North Koreans from the air, and a great deal of American artillery already zeroed in on the likely routes. They had too little artillery, and almost no air cover. This was essentially a bare-bones command. The strategy, to the degree that there was one—mostly it was just about instinct—was to try to hold the roads that led out of the east side of the Naktong Bulge toward Pusan, buying time for other American and UN forces to gather. But in any real sense, they were out there on their own. “We were really thin,” George Russell, back at Battalion headquarters, remembered, but he laughed even as he used the word. There had to be a better word, he said, and then added, “Thin to the point of being invisible.” By midnight Baker Company under Glasgow had pulled back, while Charley Company was completely surrounded and being pounded, so badly isolated and weakened that some North Korean troops had quickly slipped behind it and were already heading for the Battalion Command Post, which they reached early in the morning of September 1. They promptly swung behind it too, cutting it off; it would remain cut off for the next three days.

The moment the report came in about the torchlight assault, Colonel Paul Freeman, the Twenty-third Regiment’s commander, told his artillery to start firing. The fire was very accurate—the torches certainly helped—and it momentarily slowed down the In Min Gun, but in the end even accurate artillery fire did not seem to matter much. Back at Battalion they were caught between two conflicting needs—to hold the various company outposts for as long as they could and to get as many men as possible out so they could fight on another day. Realizing that his battalion and regimental positions were also threatened, and that the road to Pusan was the great prize, Freeman had immediately started organizing a blocking force, while signaling the units in the

forward positions to hold as long and as best they could. He dipped into his regimental reserve immediately, taking Fox Company, supported by elements of How Company, and placing them under Major Lloyd Jenson, the executive officer of the Second Battalion. Their job was to break through to Lieutenant Colonel Claire Hutchin of the First Battalion if at all possible. Failing that, and they soon failed, they were to try to establish a blocking position on the Naktong to Changnyong road.

Freeman was in a distinctly unenviable position. He had begun the battle against a vastly greater force with only two rather than the normal three battalions under his command. One of these was already completely cut off—losses were clearly going to be devastating—and parts of the other battalion could not break through to it. Because of bad weather the Air Force was no help, and Freeman’s artillery was, as ever, short of ammo. Jenson’s position, trying to block the main road to Changnyong, immediately became the main defensive position of the regiment, and a battle raged around it for the next two weeks. George Russell, who had fought in cruel, unsparing World War II battles against the Japanese in the Pacific, thought that he had never seen fighting so bitter or relentless and raw. It was the most primitive kind of warfare imaginable. The Americans fought fiercely, fearing they might be pushed off the peninsula, and the North Koreans no less intensely, knowing that if they failed here, this would be their last great strike, and they might be driven north.

Paul Freeman assigned George Company to create a blocking position that finally allowed the First Battalion to pull back on September 3 and regroup at a place they called the Switch (because it was near a former Battalion communications center known as the Switchboard). Thus was the American position significantly stabilized some forty-eight hours after the first attack. By September 3, it became clear that the North Korean Second Division was massed on the main road, and that Freeman was using almost all his troops to block it from heading directly for Pusan. As Freeman later noted, the decisions he made instantaneously in the first few hours of battle were the cruelest he would ever make as a commander. He knew he had to sacrifice certain units to buy time, even as his own regimental headquarters was being overrun on September 1, and he was just barely able to move his headquarters about six hundred yards to the rear.

UP ON THE

line near the Naktong, the end was coming very quickly. The North Koreans had rapidly encircled Charley Company and started grinding the men down, squeezing in on them. For the Americans positioned in those tiny outposts on that first night it was like seeing an enemy noose placed around your neck and rather quickly tightened. By midnight there was almost

nothing left of Charley Company. Corporal Berry Rhoden led a seven-man recoilless rifle team on that night. He was all of eighteen, a newly minted squad leader from rural Florida whose previous occupation had been as a local moonshiner. By chance that night he was in a position to watch the destruction of an entire infantry company. Because there had not been enough communications wire to go from Lieutenant Colonel Hutchin’s First Battalion CP to Bartholdi’s company CP, they had jerry-rigged a communications line to Rhoden’s outpost with a separate line to Bartholdi’s CP, several hundred yards away. So Rhoden essentially became a makeshift communications relay man and was able to hear the final anguished cries from men in a frontline unit being overrun, and the sad answer from a powerless headquarters that it could do nothing to help. It was heartbreaking, no less so because his own position was about to suffer a similar fate.

He heard Captain Bartholdi plead to Battalion for the right to release his men: “We cannot hold! Repeat we cannot hold! Our only chance is to disband and let every man get out for himself!” Rhoden had relayed Bartholdi’s message, wondering if they might somehow be able to send another battalion to the rescue, or perhaps the Air Force could fly some extra missions at the last minute. That was the way, he remembered, it always happened in the movies. But not that night, not on the east side of the Naktong. He and his own men had fought valiantly, but they had started to run out of ammunition after only forty-five minutes of battle, so when Bartholdi spoke those final desperate words, pleading for the right to slip out, he spoke for Rhoden’s squad as well. Back had come a voice from Battalion: “Hold your positions at all costs! You cannot disband. Repeat it is imperative to hold your positions at all costs! You must not disband!” Rhoden relayed that message to Captain Bartholdi, and received one last message from him asking for artillery fire or at least illuminating fire. But neither was coming. Then both wires went dead. The North Koreans had obviously cut them. Soon Rhoden heard his end of both dead wires beginning to rustle, and he knew that the North Koreans were pulling on them, trying to locate Rhoden’s position. So he cut the wires at his end. Let the sons of bitches pull on a wire that didn’t lead anywhere. It was time, he decided, to try to get his squad out of there.

Master Sergeant Graham, the leader of the First Platoon of Charley Company, thought the best thing to do was draw his men into as tight a position as he could and thus maximize their fields of fire. He knew any chance of getting out of there had gone from slim to minuscule. Graham was considered a magnificent NCO by his men. He was a lifer who never married, as if reflecting the old line of so many NCOs: if the Army wanted you to have a wife, it would have issued you one. He was known as the Bull, a generic nickname regularly

given to tough (or bull) sergeants. In the past, he had always held back in terms of personal contact with his men. He did not intend to be one of those NCOs who was tough but lovable—for him tough was enough. Years later, he would tell some of them how he had always tried to be a little too tough because he feared emotional attachment, in case he lost them on the battlefield—it would help no one and might limit his freedom to make good decisions. It’s bad enough when some of your men are killed—but so much worse when your

friends

are killed. He was, the men under him believed, the kind of sergeant who was at the core of the Army’s strength. If anyone could get them out of such a hopeless spot, it was him. Bull Graham was as good a man as they were likely to find. He would set up exceptional fields of fire, never panic, and never think of himself first.