The Cold War: A MILITARY History (77 page)

In the 1950s the French and Germans held a competition to produce a common tank design. The French entry was the AMX-30, seen here, which was lighter but less well armed and with thinner armour than the German entry. When the AMX-30 was not declared the winner, the French left the project and produced the tank for their own army

The German entry for the 1950s competition, the Leopard, was heavier than the French AMX-30 and armed with the British 105 mm gun – at that time the most powerful tank gun in the world. Once the French withdrew, the Germans produced the Leopard for the

Bundesheer

and exported it to many other armies

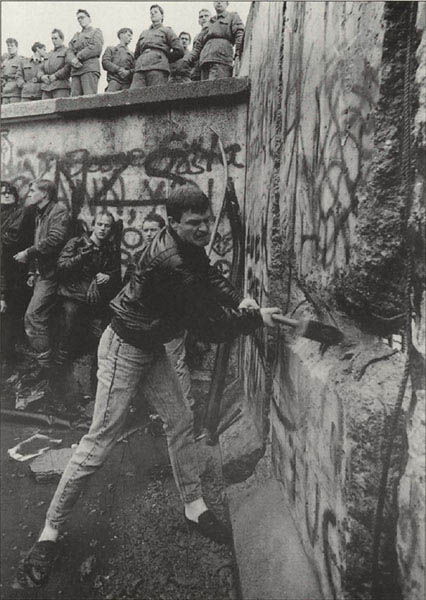

The Cold War ends in November 1989. A demonstrator hammers at the Berlin Wall, striving to demolish the hated symbol of the separation of the two Germanies. Meanwhile, East German guards look on passively, symbolizing the Communist failure to bind the nations of eastern Europe together

Notes

CHAPTER 1

1

Former British prime minister Winston Churchill in a letter to US president Harry S. Truman, November 1945; quoted in D. Cook,

Forging the Alliance: NATO 1945–1950

(Secker & Warburg, London, 1989), p. 50.

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

1

NATO Communiqué, Ministerial Meeting, 13–14 December 1967, paragraph 12.

2

Ibid., Annex, paragraph 14.

3

Soviet Military Power

was issued by the US Department of Defense, Washington DC, in 1981, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989 and 1990. A successor titled

Military Forces in Transition

, which perhaps significantly was printed in monochrome, was issued in 1991, but proved to be the final document in the series.

4

Whence The Threat To Peace?

was issued by the Military Publishing House of the USSR Ministry of Defence, Moscow, in 1982 (1st edn), 1982 (2nd edn (supplemented)) and 1984 (3rd edn).

5

NATO and the Warsaw Pact: Force Comparisons

was issued by the NATO Information Services, Brussels, in 1982, 1983 and 1984.

CHAPTER 4

1

North Atlantic Council Meeting, 11–14 December 1956, Final Communiqué, paragraph 7.

2

Tony Geraghty,

Beyond the Front Line

(HarperCollins, London, 1996), p. 159.

3

North Atlantic Council in Ministerial Session, Brussels, 15–16 November 1968, Final Communiqué, paragraph 2.

4

NATO Special Meeting of Foreign and Defence Ministers, Brussels, 12 December 1979, Final Communiqué, paragraph 7.

5

Ibid., paragraph 9.

6

NATO Communiqué, Defence Planning Committee Meeting, 1–2 June 1983.

7

NATO Nuclear Planning Group Meeting, 29–30 October 1985, Final Communiqué, paragraph 6.

CHAPTER 5

1

NATO Communiqué, Defence Planning Committee, 14 June 1974, paragraph 12.

CHAPTER 6

1

Geraghty,

Beyond the Front Line

, p. 334.

2

‘Warsaw Pact and the Polish Crisis in 1980–81’ (SED-State Research Group, Internet).

3

Raymond L. Garthoff (former US ambassador and fellow of the Brookings Institute), ‘When and Why Romania Distanced Itself from the Warsaw Pact’ (Internet:

http://www.brook.edu

).

4

Jonathan Eyal, ‘Romania: Looking for Weapons of Mass Destruction?’

Jane’s Soviet Intelligence Review

, vol. 1, no. 8 (August 1989), pp. 378–82.

CHAPTER 7

1

T. B. Cochrane, W. M. Arkin, R. S. Norris and M. M. Hoenig,

Nuclear Weapons Databook, Volume II: US Nuclear Warhead Production

(Ballinger, Cambridge, Mass., 1987), p. 154.

2

S. Glasstone and P. J. Dolan,

The Effects of Nuclear Weapons

(US Department of Defense, Washington DC, 1977).

3

Ibid., pp. 522–3.

4

SIPRI,

World Armaments and Disarmament Yearbook 1991

(SIPRI, Stockholm, Sweden), pp. 46–7.

CHAPTER 8

1

Annual Report to Congress: Fiscal Year 1987

(US Department of Defense, Washington DC, 1986).

2

V. D. Sokolovskiy,

Soviet Military Strategy

, 3rd edn, ed. H. F. Scott (Macdonald and Jane’s, London, 1975), p. 288.

3

Ibid., p. 289.

4

Sir John Hackett et al.,

The Third World War: August 1985

(Sidgwick & Jackson, London, 1978).

5

Lieutenant-Colonel G. T. Rudolph, ‘Assessing the Strategic Balance’ (paper submitted to the International Institute for Strategic Studies, London, June 1976), p. 16.

CHAPTER 9

1

Soviet Military Power: 1987

(US Department of Defense, Washington DC), p. 29.

2

Ibid.

3

D. Hölsken,

V-Missiles of the Third Reich: The V1 and V2

(Monogram Aviation Publications, Sturbridge, Mass., 1994), pp. 260–61.

4

Armed Forces Journal

, January 1980, p. 35.

CHAPTER 10

1

Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships: 1947–1995

(Conway Maritime Press, London, 1995), p. 199, and Admiral A. Baldini, ‘The Missile Systems of the Italian Navy’,

International Defense Review

, IV (1969), p. 357. According to the latter, ‘This proved to be an ingenious and interesting solution which gave completely positive results when tested.’ It is possible, although there is no evidence for this, that the planned Polaris missiles for Italy were cancelled as part of the Cuban Missiles Crisis deal, in which Jupiter land-based missiles were withdrawn from Italy and Turkey. No evidence has been found of any other NATO ships of this era actually being fitted with Polaris tubes.

2

Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships: 1947–1995

, p. 342.

CHAPTER 11

1

H. Wynn,

The RAF Strategic Deterrent Forces: 1946–1969

(Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1994), pp. 337–9.

2

A. Cave Brown (ed.),

Operation World War III: The Secret American Plan ‘Dropshot’ for War With the Soviet Union, 1957

(Arms and Armour Press, London, 1979), pp. 208–9.

3

Bill Gunston,

An Illustrated Guide to Modern Bombers

(Salamander Books, London, 1988), p. 48.

CHAPTER 12

1

Wynn,

The RAF Strategic Deterrent Forces: 1946–1969

, p. 12.

2

Ibid., p. 273.

3

Ibid., p. 276.

4

Admiral Sir Ian Easton, formal statement to the ‘Polaris Successor’ seminar held at the Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies on 30 April 1980; reported in

Journal of the Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies

, vol. 125, no. 3 (September 1980), p. 19.

5

David S. Yost,

France’s Deterrent Posture and Security in Europe, Part I: Capabilities and Doctrine

(International Institute for Strategic Studies, London, Adelphi Paper No. 194, winter 1984/85), p. 14.

6

R. S. Norris, et al.,

Nuclear Weapons Databook, Volume V: British, French and Chinese Nuclear Weapons

(Westview Press, Boulder, Col., 1994), p. 385.

7

United States Military Posture for FY 1983

(The Organization of the Joint Chiefs-of-Staff, Washington DC, 1982), p. 117.

CHAPTER 13

1

Barbara G. Levi, Frank N. von Hippel, William H. Dogherty, ‘Civilian Casualties from “Limited” Nuclear Attacks on the USSR’,

International Security

, vol. 12, no. 3 (winter 1987/88), pp. 168–9. The strike plan on which their study was based is given in Appendix 28.

2

NATO: Facts and Figures

, 11th edn (NATO Information Service, Brussels, 1989), p. 259.

3

Norwegian Defence: Facts and Figures

(Royal Ministry of Defence, Oslo, 1995), p. 37.

CHAPTER 14

1

Norris et al.,

Nuclear Weapons Databook, Volume V

, p. 363.

2

Cochrane et al.,

Nuclear Weapons Databook, Volume II

, pp. 50–51.

3

Max Walmer,

An Illustrated Guide to Strategic Weapons

(Salamander Books, London, 1988), p. 67.

4

Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships: 1947–1995

, p. 356.

CHAPTER 19

1

Sokolovskiy,

Soviet Military Strategy

, p. 300.

CHAPTER 23

1

NATO Military Committee Document MC-14/2 (NATO Headquarters, Fontainebleau, 1956).

2

The Falklands Campaign: The Lessons

(Cmnd 8758, Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, London, 1982), paragraph 243.

3

UK Royal Navy,

General Statistics

(D/DPR/129/3/11/9, dated 17 April 1991).

CHAPTER 24

1

Sokolovskiy,

Soviet Military Strategy

, p. 250.

2

NATO and the Warsaw Pact: Force Comparisons

(NATO Information Services, Brussels, 1984).

CHAPTER 25

1

A. J. Alexander,

Armor Development in the Soviet Union and the United States

(Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, 1976), p. 127.

CHAPTER 31

1

Sokolovskiy,

Soviet Military Strategy

, p. 141.

2

Sun Tzu,

The Art of War

, trans. and intro. Samuel B. Griffith (Oxford University Press, London, 1963), p. 69.

3

Details of the NATO Alert Systems are contained in PRO DEFE 5/166 (Chiefs-of-Staff Paper 27/66) and in PRO FO371/190667.

CHAPTER 32

1

‘Declaration Regarding the Defeat of Germany and the Assumption of Supreme Authority by the Allied Powers’, signed in Berlin at 1800 hours Central European Time, 5 June 1945, by General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower (USA), Marshal of the Soviet Union G. Zhukov (USSR), Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery (UK) and General J. de Lattre de Tassigny (France).

2

Paper JP(62)6 (Final), dated 19 June 1962, in PRO/DEFE 11/489.

3

J. J. Sokolsky,

Seapower in the Nuclear Age: The United States Navy 1949–80

(Routledge, London, 1991), pp. 61, 74.

4

PRO/DEFE 11/491.

5

R. J. S. Corbett,

Berlin and the British Ally: 1945–1990

(published privately, 1992), p. 62.

6

Ibid., p. 94.

CHAPTER 33

1

T. B. Cochrane, W. M. Arkin, and M. M. Hoenig,

Nuclear Weapons Databook, Volume I: US Nuclear Forces and Capabilities

(Ballinger, Cambridge, Mass., 1984), pp. 30–31.

2

News Conference, 3 January 1955.

3

Annual Report to Congress: Fiscal Year 1975

(US Department of Defense, Washington DC, 1974), p. 82; quoted in W. van Cleave and S. T. Cohen,

Tactical Nuclear Weapons: An Examination of the Issues

(Macdonald and Jane’s, London, 1978).

4

Annual Report to Congress: Fiscal Year 1982

(US Department of Defense, Washington DC, 1981), p. 129.

5

United States Military Posture for FY 1983

(The Organization of the Joint Chiefs-of-Staff, Washington DC, 1982).

6

Sir Solly Zuckerman to the British minister of defence, 7 August 1962 (PRO DEFE 13/254).