The Clitoral Truth: The Secret World at Your Fingertips (6 page)

Read The Clitoral Truth: The Secret World at Your Fingertips Online

Authors: Rebecca Chalker

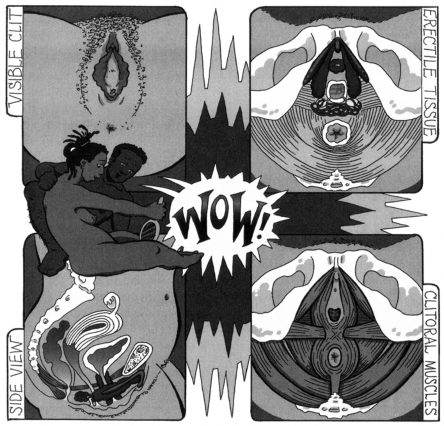

ACCORDING TO THE FFWHCS, THE COMPLETE CLITORIS CONSISTS OF EIGHTEEN PARTS:

the clitoral Junction (or front commissure, the point where the outer lips meet at the base of the pubic mound. marking the upper extent of the visible clitoris).

the glans.

the inner lips, or ‘labia minora,’

the hood.

the bridle, or frenulum, the point where the outer edges of the inner lips meet just below the glans.

the fork, or “fourchette,” the membrane stretched above the point where the lower edges of the inner lips meet below the vaginal opening, marking the lower extent of the visible clitoris.

the hymen, or its remnants, which are visible just inside the vaginal opening.

the shaft, which connects the glans and the legs.

the legs, or crura, two elongated bodies of erectile tissue shaped like a wishbone.

the bulbs, two large bodies of corpus cavernosum erectile tissue corresponding to the single bulb of the penis.

the urethral sponge, a body of corpus spongiosum erectile tissue surrounding the urethra.

the paraurethral glands: the female prostate glands.

the vulvovaginal, or Bartholin’s, glands, which produce a small amount of lubrication outside of the vagina.

the perineal sponge, or perineal body, a dense network of blood vessels that lies underneath the perineum.

the pelvic floor muscles:

the bulbocavernosus (BC) muscle, which lies underneath the bulbs of the clitoris and the anal sphincter (AS) muscle.

the ischiocavernosus (IC) muscles, which outline the triangular pelvic opening, or outlet, and are attached to the bones we sit on.

the transverse perineal (TP) muscle, the broad band of muscle that outlines the bottom of the pelvic opening and is interwoven with the intersection of the bulbocavernosus muscle and the anal sphincter muscle.

the urogenital diaphragm (UD), the flat, triangle-shaped muscle that lies under the pelvic opening.

the levator ani (LA) muscle, a part of the pelvic diaphragm, the broad, flat, funnel-shaped muscle that is the bottom of the pelvic floor.

the suspensory ligament and the round ligament

the nerves: the pudendal nerve, or, as I prefer to call it, the genital nerve complex, and possibly the hypogastric nerve, which carries messages back and forth from the uterus.

the blood vessels, which bring a greatly increased blood supply to the pelvis during sexual response.

NOW THAT’S SOME POWERHOUSE!

FIGURE 6: THE COMPLETE CLITORIS

the vagina forces clear fluid from the blood through the walls of the arteries and then through the walls of the vagina, producing the “vaginal sweat” that serves as a lubricant. This is not actually sweat containing urea and other waste products but a part of the blood serum. The vulvovaginal glands located near the base of the vaginal opening produce a small amount of a thicker viscous fluid, which also serves as a lubricant.

As stimulation continues, the muscles and ligaments begin to contract in response to messages from the brain, creating what we call “sexual tension.” The suspensory ligament shortens and pulls the glans back underneath the hood, where it will probably remain until orgasm. (The glans can still be felt, but not as easily.) The end of the round ligament tugs on the inner lips on one end, and the uterus on the other, creating tension and pleasurable sensations in the inner lips and involving the uterus in the orgasmic process. In the meantime, muscle tension builds to a crescendo and all of the clitoral tissues become hypersensitive due to the increased blood supply. The blood stream is now saturated with sexual chemicals and the skin on the rest of the body—the face and neck, abdomen, buttocks, hands, and feet also becomes more sensitive, but you may hardly be aware of it, since the brain is now awash in naturally produced mind-altering substances. At some point, like an overloaded electrical circuit shorting out, the muscular tension explodes in a series of quick, rhythmic contractions, partially expelling blood from engorged

tissues and releasing a further cascade of hormones, peptides, and opioids in the bloodstream and, ahhhhhhhhhhhh... orgasm!

Your orgasms may not seem like the idealized one described here. There are many different types: mini-orgasms; maxi-orgasms; quickie orgasms; explosive orgasms; multiple orgasms; dry, non- ejaculatory orgasms; extended orgasms, which can last anywhere from a few minutes to several hours; focused orgasms (experienced primarily in the genitals); irradiating orgasms, which may be felt in the pelvis and upper thighs; full-body orgasms; out-of-body orgasms (feels like it, anyway); well-earned orgasms; unconscious orgasms (the fabled “wet dreams,” which may or may not involve genital engorgement and occur in both women and men); even involuntary orgasms, and so on. Sexologists generally agree that only the person experiencing an orgasm can adequately describe it. Therefore, the reasoning goes, only you can be the judge of the quality of an orgasm. In my view, there are no “bad” orgasms, just shorter, longer, weaker, stronger, and when time and circumstances permit, the much vaunted Vesuvian ones.

Beverly Whipple and Barry Komisaruk have proposed the concept of an “orgasmic process” in which sexual tension builds to a peak and orgasm occurs, followed by relaxation. t0 Having an orgasm, they say, is something like walking up a flight of stairs. Sequential steps must be taken in order to reach the top of the staircase. During sexual response, as sensory messages are sent

toward the brain, increasing numbers of nerves become activated, reaching and then surpassing a threshold for activating another system. In other words, when one system reaches a certain peak of excitation, the nerve activity that it generates “recruits” or affects the next system along the chain. When all of the steps have been taken, and all of the systems are at a high level of excitability, they may reach a point of overload and discharge, causing an orgasm. These researchers also suggest that orgasms are most efficiently achieved if stimulation occurs “in phase” in a rhythmic cycle—what they call an “excitability cycle”—which is linked to the heartbeat: “The recruitment process possesses as an inherent property a rhythmically fluctuating level of excitability, i.e., an ‘excitability cycle.’“ This can be achieved, for men and some women, by the rhythmic thrusting of intercourse. For many women, as well as men, rapid hand movements, a vibrator, rhythmic leg motion, or other types of stimulation can create an effective excitability cycle that can result in orgasm. We know, of course, that orgasm can also occur without any of these types of mechanical stimulation.

This concept reveals, I think, why many women don’t have orgasms all of the time. They simply aren’t getting enough of the kind of stimulation and rhythm for a long enough time to recruit all—or enough—of the systems to cause an overload and explosive discharge of orgasmic energy. This is why masturbation is such an important learning mechanism. When we are by ourselves, perhaps

aided by our favorite vibrator, some erotica, maybe some music, and anything else that helps us feel sexy and sexual, we can practice different types of stimulation for varying periods of time. If hands don’t do the job, maybe a vibrator or other sex toy will. Given what I’ve learned about sexual response, I believe that any woman, from those who have never had an orgasm to those who are easily orgasmic, can have more and better orgasms by learning some basic anatomy and discovering what feels good.

Whipple and Komisaruk point out that their definition encompasses orgasms that are “characteristic of, but not restricted to the genital system.” This is an extremely important feature of this definition, since feminists and sexologists have long promoted the concept of full-body sexual response and full-body orgasm, as opposed to the genitally focused orgasm, which has been the gold standard of male centered sexuality.

A clear understanding of clitoral anatomy provides important information for women who have had their genitals mutilated (female genital mutilation, or FGM). In the less extreme version of female genital mutilation, only the glans is removed. In more drastic procedures, the glans, hood. shaft, and inner lips may be excised and the edges of the outer lips sewn together with small

openings left to drain urine and menstrual blood. The job is often done with dull, un-sterile instruments. In the best-case scenario, where just the glans is excised, women may suffer decreased sexual sensation but they are still able to have orgasms. In the more radical forms of mutilation, however, women may develop infections that can be chronic or life-threatening, painful, or may restrict movement. Some women may also experience searing pain during intercourse. During each childbirth, the incision must be cut to allow for passage of the baby, and then resewn. Birth-related risks to both mother and infant increase dramatically. Cultures that place a high premium on virginity rationalize this ancient ritualistic practice as essential to discourage young girls from losing their virginity and becoming unmarriageable. Though the practice is intended to preserve a girl’s virginity, it actually decreases fertility and reproductive ability. Genital mutilation does not prevent her from wanting to have sex, either. We now know that the biggest part of sex is psychological and hormonal. Thus, it is impossible to control the desire for sex through surgery, unless you remove part of the brain. And knowing what we now know about the extent of the clitoris, it is clear that no matter how it is removed, the erectile tissues, glands, muscles, and nerves that are involved in sexual response cannot be

diminished. Even women who have had the most severe mutilation still have “the powerhouse of orgasm” intact, and if their pain is not too great, they should still be capable of experiencing a wide range of sexual response—even orgasms. The same may be true for people who have had their genitals altered through illness or accidents.

A precise understanding of the extent and function of the genitals might also be enormously helpful to women and men who are exploring transgender roles or identities, or who are considering gender reassignment surgery. Until recently, surgery was thought to be essential for many transsexuals. Today, it is understood that the genitals are only one factor—and not even the most significant factor—in gender identity. As a consequence, a wider, more fluid continuum of gender identities has evolved that enables many people to find comfortable sexual personas without surgery. Knowing that women, men, and even those who have ambiguous genitalia have essentially the same genital structures arranged in one way or another, could be useful information for people contemplating gender reassignment surgery.