The City of Dreaming Books (73 page)

Read The City of Dreaming Books Online

Authors: Walter Moers

Smyke’s triumphant smirk vanished. In his mind’s eye he had probably seen the Shadow King go up in a sheet of flame and turn to ashes beside the window, but now he was horrified to find that his creation still possessed the strength to move.

Sheet after sheet of alchemical paper caught fire, hundreds of lambent flames were already writhing in the air, each a different colour. With a menacing hiss, sparks shot out of the multicoloured inferno and adhered to the surrounding wood and paper, setting them ablaze. Tiny fire devils flickered along the laboratory’s shelves and up its walls, igniting the wallpaper.

The Shadow King strode on, steadily closing the gap between himself and Smyke, who had at last found the strength to retreat.

‘What do you want of me?’ he cried in a reedy falsetto.

But Homuncolossus grew and grew, becoming ever brighter, an incandescent figure from which liquid fire was dripping. And then he started to laugh the rustling laugh of the Shadow King. It was a long time since I’d heard it and suddenly my tears ceased to flow, for I sensed that he was happy at last. Happy and free.

He paused once more as he passed me and raised his hand in farewell, a crackling torch with white sparks gushing from it. He was now a single flame, a sight of unforgettable beauty. And for one brief moment, the space of a heartbeat only, though it might also have been my imagination, I thought I saw his eyes for the first and last time. They were sparkling with the unbridled happiness of a child.

I too raised my hand in farewell and he turned back to Smyke, who was now slithering down the wooden ramp in a panic.

‘What do you want?’ Smyke called shrilly. ‘What do you want of me?’

But the Shadow King merely followed him like a vortex of hissing flame that ignited all it touched. And he laughed as he descended into the cellar - he laughed with all his might. I could still hear him long after he had disappeared below ground.

A flask exploded. I looked round as if awaking from a dream. That was when the full danger of the situation dawned on me. The whole laboratory was on fire: the tables and chairs, the wooden ramp and the beams in the walls, the shelves and books, the carpets and wallpaper, even the lengths of knot-writing suspended from the ceiling. Chemical fluids were boiling in the glass alembics, acids spurting, corrosive vapours and biting smoke rising into the air.

The heat had set many of the absurd Bookemistic machines in motion. Their cogwheels were turning, their flaps opening and shutting as if they had come to life and were eager to escape the conflagration.

Just before my cloak could catch fire I caught a last glimpse of the chest full of inestimably valuable books. It wasn’t a rational act on my part, just an instinctive desire to save at least one of them from destruction: I snatched up the topmost volume and fled outside.

The Orm

T

he street was quiet and deserted, the air fresh and cool: it was a perfectly normal sunny day in Bookholm. I had dreamt of this moment for so long, and now it meant nothing to me.

he street was quiet and deserted, the air fresh and cool: it was a perfectly normal sunny day in Bookholm. I had dreamt of this moment for so long, and now it meant nothing to me.

I paused outside Pfistomel Smyke’s house and waited for the first wisps of smoke to seep through the shingled roof. Then I turned and walked off - slowly, because I had no further need to hurry. It took some time for any alarming noises to make themselves heard - bells ringing, a babble of agitated voices, the clatter of horse-drawn fire engines - but the smell of smoke soon pursued me as relentlessly as if the blazing Darkman of Bookholm himself were at my heels.

Hear the loud Bookholmian bells -

brazen bells!

What a tale of terror, now, their turbulency tells!

In the startled ear of night

how they screamed out their affright!

Too much horrified to speak,

they can only shriek, shriek . . .

brazen bells!

What a tale of terror, now, their turbulency tells!

In the startled ear of night

how they screamed out their affright!

Too much horrified to speak,

they can only shriek, shriek . . .

Those lines from Perla la Gadeon’s poem kept running through my head as I walked on, passing house after house, street after street and district after district until the City of Dreaming Books itself lay behind me. I had reached the city limits, where Bookholm and everything else had begun so unspectacularly. But I didn’t stop even then. I simply walked on staring doggedly ahead, further and further across the deserted plain.

At last, dear readers, I summoned up the courage to pause and look back. The sun had set by now, and the burning city was surmounted by a cloudless, starry sky and an almost full moon.

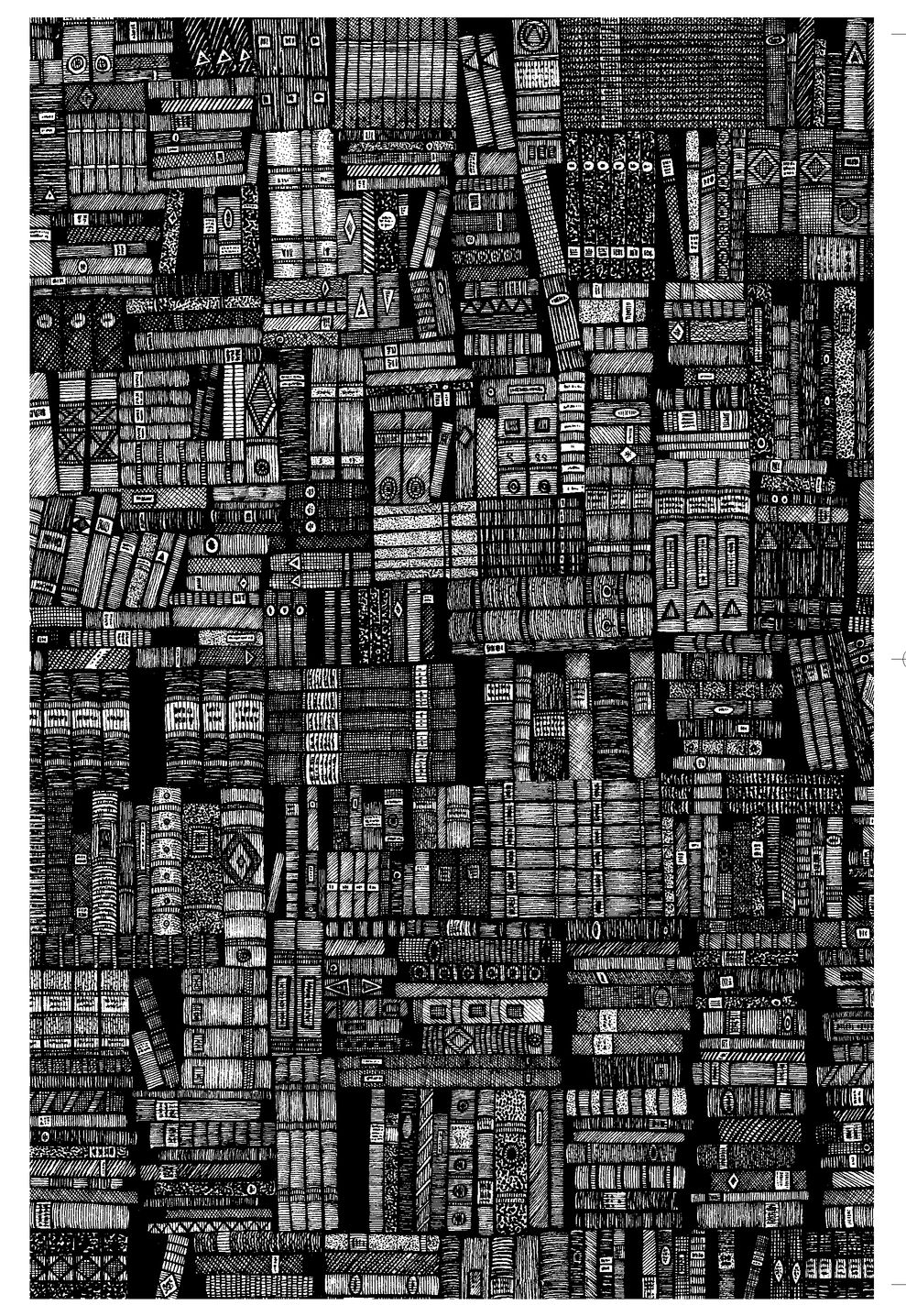

The Dreaming Books had awakened. Miles-high columns of black smoke were rising into the heavens fraught with paper transformed into weightless ash: the residue of incinerated thoughts. Swirling within them were myriads of sparks, every one a fiery word ascending ever higher to dance with the stars.

And then I saw it up above: the Alphabet of the Stars. It sparkled in the firmament, clear and distinct, a spider’s web of silvery threads entwined amid the celestial bodies.

Below, the bells continued their senseless tolling. The rustle of the countless awakening books reminded me sadly of the rustling laughter of my friend the Shadow King, the greatest writer of all time. It occurred to me only then that I had never asked him his real name. He, too, was ascending in the biggest, most terrible conflagration Bookholm had ever undergone. He, the original spark and author of that conflagration, was soaring heavenwards to become a star that would shine down for ever on a world too confined for a spirit as great as his.

That was the moment when I first felt the Orm. It surged over me like a hot wind, but not from the fires of Bookholm. Originating in the uttermost depths of space, it swept through my head and filled it with a maelstrom of words that swiftly, within a few excited heartbeats, arranged themselves into sentences, pages, chapters and, finally, into the story you have just read, my faithful friends!

And I joined in the Shadow King’s laughter, which now seemed to resonate from all directions, from the all-consuming flames of Bookholm and the stars of the firmament. I laughed and wept until no vestige of that frenzied feeling of joy remained within me.

I recalled Al’s farewell recitation in the Leather Grotto, which now at last made sense to me. It was as if the author whose spirit lived on in that little Bookling had looked into the future on my behalf and foreseen this moment, the moment when I received the Orm:

Had I but died an instant before this chance,

I had liv’d a blessed time; for from this instant,

there’s nothing serious in mortality;

all is but toys; renown and grace is dead,

the wine of life is drawn, and the mere lees

is left for Bookhunters to brag of . . .

I had liv’d a blessed time; for from this instant,

there’s nothing serious in mortality;

all is but toys; renown and grace is dead,

the wine of life is drawn, and the mere lees

is left for Bookhunters to brag of . . .

Now, for the first time, I examined the book I had snatched from the inferno in Pfistomel Smyke’s laboratory. I could not repress a shudder when I saw that it was, of all things,

The Bloody Book.

Averting my gaze from the sight of the burning city, I walked on without another backward glance.

The Bloody Book.

Averting my gaze from the sight of the burning city, I walked on without another backward glance.

And now, dear readers, you courageous friends who have so fearlessly accompanied me thus far - now you know how I came into possession of

The Bloody Book

and acquired the Orm. There is nothing more to tell.

The Bloody Book

and acquired the Orm. There is nothing more to tell.

For this is where my story ends.

Translator’s Postscript

Although I esteemed it a privilege to select material for translation from Optimus Yarnspinner’s oeuvre, it proved to be an intellectual marathon. I devoted years to the task, overwhelmed and intimidated by the sheer magnitude of his output. Yarnspinner produced hundreds of novels, thousands of short stories and poems, and a score of monumental stage plays that took months to perform. He also wrote a number of books under pseudonyms: Thelonius Orm, Wilfred the Wordsmith, Hildegard Mythmaker and Oscar van Tripplestock, to name but a few. I eventually decided to proceed chronologically. The earliest book by Yarnspinner to be published in Zamonia was

Memoirs of a Sentimental Dinosaur

, but the first edition encompassed over 10,000 pages and would have taken me a lifetime to translate had it been published unabridged. That being so, I resolved to extract the first two chapters from the aforesaid novel and lump them together under the title

The City of Dreaming Books

. I trust I shall be forgiven for having taken such an editorial liberty, but I firmly believe that these fragments possess all the makings of a book in its own right.

Memoirs of a Sentimental Dinosaur

, but the first edition encompassed over 10,000 pages and would have taken me a lifetime to translate had it been published unabridged. That being so, I resolved to extract the first two chapters from the aforesaid novel and lump them together under the title

The City of Dreaming Books

. I trust I shall be forgiven for having taken such an editorial liberty, but I firmly believe that these fragments possess all the makings of a book in its own right.

Walter Moers

Other books

Broken Fall: A D.I. Harland novella by Fergus McNeill

Highway Robbery by Franklin W. Dixon

Away With the Fairies by Twist, Jenny

18 - The Unfair Fare Affair by Peter Leslie

What Happened in Vegas by Day, Sylvia

The Devil on Horseback by Victoria Holt

Love & Curses (Cursed Ink) by Gould, Debbie, Garland, L.J.

Don't Ask by Donald E. Westlake

Shadow Man (Paragons of Queer Speculative Fiction) by Scott, Melissa

Passionate Ink by Springer, Jan