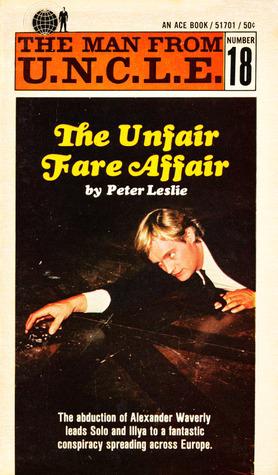

18 - The Unfair Fare Affair

Read 18 - The Unfair Fare Affair Online

Authors: Peter Leslie

THE UNFAIR FARE AFFAIR

Chapter 1

Mr. Waverly Is Taken For A Ride!

IT WAS NOT at all the kind of affair in which the sophisticated operatives of U.N.C.L.E. usually found themselves embroiled. Indeed, the Command would probably never have been brought into it at all except that the Policy and Operations chief of Section One unexpectedly found himself suffering the pangs of hunger one wet afternoon in Holland.

Alexander Waverly, however, did find himself thus famished that day and decided to seek a shortcut back to his hotel in Amsterdam. And that's when the trouble started. For in taking this step he inadvertently stumbled on the first small pointer that was to lead the United Network Command for Law and Enforcement into one of the most bizarre assignments ever handled by those superlative agents Napoleon Solo and Illya Kuryakin.

Waverly had been attending an Interpol conference in the Dutch capital and had chosen, even though it was winter, to stay on for a few days' vacation in Holland.

He had listened to the carillons and barrel organs of Amsterdam, and he had made the tour of the canals. He had been to Delft, to Leiden, and to Arnhem; he had visited the radio station at Hilversum and the Philips electronics empire at Nijmegen. He had admired the superlative planning of Rotterdam's postwar shopping center, and he had found him self a boy again amid the miniature docks and airfields and city streets of the model town of Madurodam, near Scheveningen. And today he had made up his mind to take a walk in the country for a change.

It had been a fine morning, and he had taken a bus all the way to Amersfoort and then another up to Harderwijk, which lay eastward from Amsterdam across a stretch of what had once been the Zuider Zee.

After a modest lunch in a dark-beamed

bodega

whose tables were spread with covers resembling squares of red-flowered carpet, he had decided to cross over to Oost Flevoland. The island of reclaimed land was featureless and flat in the wintry sunshine. On one side of the dike carrying the road along which he walked were inundated fields. On the other, the cold gray waters of the Ijsselmeer stretched away to the cranes and funnels and mellowed brick waterfronts of Amsterdam. And ahead, an irregular line of trees apparently growing out of the desolate sea marked the position of the Noordholland peninsula just over the horizon.

He had walked about five miles, a third of the distance to Lelystad, when the sun withdrew behind a dark bank of clouds that had blown up from the west.

Waverly hesitated. He scanned the sky, and his lean, creased face crumpled into an expression of irritation. He had intended to go on to the town in the hope of getting a ear to take him to Kampen, back on the mainland, and then Zwoll—from which he could have caught a bus back home. But it was getting confoundedly overcast and cold; it looked like rain... and there was this sudden ache in his middle that told him he needed food.

Abruptly he turned about and retraced his steps. He would go back the way he had come. It would be much quicker in the long run, he would be able to eat sooner, and if he was lucky, he would find a shortcut and avoid following the curve of the coast the way he had on the outward journey.

The island was crisscrossed by dikes. Soon he found one leading inland in the direction he wanted, and he left the road.

He had been walking along the waterlogged path for only a few minutes, when there was a low murmur of wind, stirring the grasses at his feet, and a squall of fine rain blew past him like a cloud of smoke.

Soon a persistent drizzle was falling from the pewter sky. It rolled up behind him from the west, dewing the shoulders of his light tweed topcoat, soaking his trousers behind the knee, and trickling down his neck. Amsterdam had disappeared in the mist, and the ripples flowing across the Ijsselmeer were breaking into tumbles of gray foam.

Somewhere ahead there were osiers and clumps of alder shielding a mansarded slate roof—though whether the building was on the island or across on the far side of the water he could not yet see.

Below the dike, the green of the drenched

polder

was almost indecently bright beneath the sullen sky. Farther away, plowed fields were awash, the tops of the ridges barely surfacing above the water in the furrows. A long way to the south, the domed tower of a church rose above the flat land, but otherwise there was no sign of life; not even a windmill, Waverly thought bitterly, to look at!

When he came at last to the strip of water dividing Oost Flevoland from the mainland, he found to his disgust that he had miscalculated: he was nowhere near the bridge, and there wasn't a causeway or a ferry to be seen.

Fuming, Waverly hunched deeper down inside the wet collar of his coat and squelched along the waterlogged grass at the water's edge.

Before long he rounded a spinney and found himself a few yards away from a boatman sitting inside a crude wooden shelter. At his feet a kind of punt rode the rain-pitted swell lapping at the sandy bank. Waverly looked over the channel. It was about three hundred yards across. Beyond a belt of trees on the far side, he could see the roofs of a village and the gleam of passing traffic on a road. From over there, surely, he would be able to get a car....

"Good day," he said in German, approaching the boat man. "I'm afraid I seem to have missed my way. Could you possibly take me across?"

"Where are you from?" the boatman grunted, rising to his feet. He was a tall man, raw-boned and craggy.

Waverly was thinking of something else. "I'm from Section One," he said absently. "Er… that is to say, I have just walked—"

"Right," interrupted the big Dutchman. "In you get, and we'll be on our way then. I've been sitting around for long enough in this perishing rain!" He reached out with one foot and drew the boat to the bank. Waverly stepped in and sat down gingerly on a wet thwart as the man took a long pole and thrust off.

For a time, the man from U.N.C.L.E. watched the two identical lines of damp countryside, one receding, the other approaching, as the boatman poled them out into midstream with long, powerful strokes.

Then, feeling a little guilty because, after all, the man didn't have to oblige him at all, he tried to make conversation.

"It's very kind of you," he began. "Still... I don't suppose you get too many people asking to be ferried across at this time of the year!"

The man grunted.

"It was most fortunate for me," Waverly pursued, "that you just happened to be there at that time. You are yourself a fisherman, I imagine?" He looked expectantly at his pilot.

"Best not to talk," the boatman said. "The less anyone knows about anyone else the better, eh?"

Waverly shrugged. The fellow seemed to be a bit of a boor. He stared for a while at the gray water sliding past the stem. Judging from the watermark on the pole, it could be no more than four or five feet deep.

When they were about two-thirds of the way across, the boatman stopped poling and allowed the punt to drift to a stand "Perhaps we'd better settle up now?" he suggested dourly. "Don't want to hang about too much by the bank, do we? It may be all right for Willem on the other side of the island, where there's nobody to see, but we have to be more careful. Anyway, I expect you'll want to be off as quick as you can. Your lot always do."

"Why... why, yes, by all means," Waverly said, reaching for his wallet. "How much do I owe you?"

He wasn't really thinking. He was cold and he was wet and he was miserable. He had had only a quarter of a chicken for lunch and that had soon vanished in the exertion of his five-mile walk. In his famished state, he could think only of getting back to his hotel—and to a large, hot meal!

The boatman had walked forward, rocking the flat-bottomed craft on the surface of the water. "One hundred guilders," he said curtly, balancing the pole across the width of the punt and holding out his hand.

Perhaps, Waverly thought, counting notes into the callused palm, he would be able to find one of those splendid Indonesian restaurants open early; a selection from the famous

rijstafel

would just about fit the bill... twenty and ten makes thirty, and five is thirty-five... and talking about hills... "

A hundred guilders

!" he screeched suddenly, his hand in midair. "But that's almost thirty dollars!"

The boatman stared at him impassively. He said nothing.

"Thirty dollars? For crossing less than a quarter of a mile of dead calm water? You must be out of your mind!"

"A hundred guilders. That's the price."

"But that's monstrous! I wouldn't dream of paying such a price! I absolutely refuse. I—"

"Look—the fare is paid," the man said strangely. "This is extra for me. For waiting. For the weather. For whatever you like. But you either give me the money or I tip you into the water... " He rocked the frail craft from side to side threateningly. "You takes your choice and you pays the money," he added with a crooked grin as he inverted the old saw.

Waverly was speechless with rage. "This is blackmail!" he stammered at last. "It is an outrage. I... I never had such a—"

"Shut up. If the cash was so important to you, you should have made sure Willem got you here earlier. You have had all day, after all. Come now—decide!"

Waverly was so angry he could hardly think straight. God knew what all that garbage meant! What the devil had this extortion to do with Willem—whoever he was? All the same, the boatman was a

very

big man—and he had already parted with nearly half the money. Also, even if he demanded to be taken back, he would be no better off; in fact, he would be back where he had started, with no means of crossing and thirty-five florins less in his pocket! He glanced at the oily surface of the water—it looked extremely cold!—and shuddered. Scowling, he counted out the rest of the money.

"There! That's better!" The boatman was suddenly almost affable. He stuffed the notes into his hip pocket, took up the pole, and began punting the boat rapidly toward the bank.

"Will I be able to get a car?" Waverly growled a few minutes later. "I'm in a hurry—otherwise I should never have paid your outrageous price—and I want to go—"

"Don't worry!" the giant interrupted. "Of course you'll get a car. It's all taken care of. You fuss too much."

Waverly shrugged in his wet coat and fell silent. A final thrust of the pole had sent them gliding toward a narrow creek penetrating a thicket of alders at the water's edge. Soundlessly, they slid in beneath the branches.

"You'll have to give me a hand," Waverly snapped. "There's a bank here, it's too steep and too wet and slippery to climb unaided."

"I told you not to worry," the boatman said—and indeed, as he spoke, arms reached down through the screen of leaves and hauled Waverly up and out of the boat. A few scrambling steps later, he was panting on top of the bank, staring at two men in heavy belted coats and soft hats.

"Come on if you want the car," the taller of the two murmured. "It has already attracted enough attention as it is." Taking Waverly's arm, he drew him through the bushes toward a footpath running along one side of a drowned field.

"But I didn't... " Waverly glanced over his shoulder. The punt was already back in the open water, the tall figure of the boatman blurred by the clouds of drizzle gusting in from the island.

"Best not to talk," the shorter man said.

Ten minutes and three fields later, they emerged from a belt of trees to find themselves at the edge of a country road. On the far side, a huge Minerva taxi stood in a side road half-hidden by a pile of stones.

The short man looked each way and then beckoned them across. He leaned in and spoke to a chauffeur in a peaked cap while his companion opened a door and ushered Waverly into the vast back seat. He sank down with a sigh of relief on the stained Bedford cord upholstery.

Before he could say anything, the door was slammed, the engine sprang to life, and the huge car surged forward on to the road.

Waverly twisted around and looked out the oval rear window. The two men, dwindling now in the approaching dusk, were standing in the middle of the road, each with a hand raised to the brim of his hat. He shrugged his damp shoulders and settled himself well back on the seat of the old Belgian car. He had stopped trying to figure it out… perhaps the exorbitant ferry fee included conducting him to a taxi. Yet nobody could have known he was coming; it was obviously not a regular ferry. In which case—how had there happened to

be

a taxi and men to take him to it?

He realized suddenly that he had given the driver no instructions. Would he go automatically to Amsterdam, because there was no civilized place in the other direction? Unable to recall the map, Waverly stared through the rain drops pockmarking the windows.

They were rattling along a narrow cobbled road that ran beside a canal. On either side, yellowing leaves drooped dispiritedly from the bare wet branches of trees.

Soon they passed a wooden bridge spanning the canal. At the corner of the timber superstructure, there was a three- finger signpost. The white-painted boards read: HARDERWIJK, ERMELE, AMSTERDAM... ELBURG, OLDEBROEK... and, on the one pointing across the canal: NUNSPEET.