The Cinnamon Tree (23 page)

Authors: Aubrey Flegg

There is a cinnamon tree, and there was a landmine under it. I could see the rim of it sticking out through the red earth before Vincent, an Angolan

deminer

, sent me away so that he could lift it and make it safe.

In 1998 I travelled to Angola, inspired by Princess Diana, who had

chosen

to wake the world to the evil of landmines by visiting this, the landmines capital of the world. I wanted to write this book, but first I needed to meet the victims and to see how landmines were located and dealt with. Angola has been at war for thirty-eight years: first a war of independence from

Portugal

, and then twenty-four years of civil war. During this time, ten million landmines have been laid there, most of which are still in the ground. Over 70,000 people have lost limbs and many, particularly children, have died.

But Kasemba, my imaginary country, is not Angola. You will not find it on a map of Africa, nor will you find a Yola or a Gabbin quite as I describe them. Nevertheless, much of what I have told in

The Cinnamon Tree

is real.

There are a number of demining groups in Angola, but I was looked

after

by a wonderful organisation called Norwegian People’s Aid. In

The

Cinnamon

Tree

, when Yola travels from Nopani to Simbada, I am describing a trip very like my own from Luanda, the capital of Angola, to Lobito, where Norwegian People’s Aid have their field-station. It was there that I saw dogs being trained to sniff out mines. I watched a beautiful German Shepherd looping left and right, just as Sailor did for Yola on her nighttime

expedition

, his tail waving with excitement. Then he sank to the ground, his

Angolan

handler marked the spot and a supervisor came with a spade and carefully dug up a large anti-tank mine. Incidentally, Yola’s nighttime

expedition

was far more dangerous than she realised. Responsible deminers would not walk into a minefield like that.

Later, I was taken to the little town of Gabela, where I saw a real

mineclearance

in operation. There was a hill, and a Russian tank – just like the one Gabbin was playing in when he lost Managu the bull – but there were no boys near the tank while I was there. Discipline was tight. The Angolan deminers worked in pairs, each pair fifty metres apart, in case of accidents. Only a week before, a deminer had been injured when he accidentally pulled a tripwire attached to a hand grenade in the bushes. Vincent, the supervisor,

showed me a stake marking the place where they had recently found a

landmine

. Beside the spot was a bent stick with a piece of string attached. It was a bird trap, set by some youngster while the mine was still in the ground. When he knelt to set his trap, he was only centimetres away from the mine. Later that day, Vincent called me over to look at a mine they had uncovered under a tree. He pointed out how it had been placed there so that anyone trying to climb the tree would step on it, a soldier or a sniper perhaps – or even a girl like Yola. Vincent took his knife out and broke off a piece of the bark, smiling as he asked me to smell it. Yes, the smell was cinnamon.

For Yola’s family life I turned to the people that I had lived among once for a year, on the shores of Lake Victoria in Kenya. Here important men, like Yola’s father, often had several wives. By giving a good bride-price for a new young bride, the wealthy man could help a neighbour and, at the same time, get welcome help for his senior wife. Often this worked well, even for the young bride. She moved from being a drudge at home, perhaps, to being the wife of an important man, with both status and security. If there were problems it was the senior wife who kept the peace. In Africa, age and

wisdom

are respected. Any man of importance is expected to show wisdom and good judgement. Father, with his almost telepathic understanding of people, is a portrait of a wise Kenyan I knew.

How is it then that wise and gentle people find themselves locked in war? One of the reasons is that unscrupulous people make money out of selling arms. In

The Cinnamon Tree

, Mr Birthistle represents the underbelly of the arms trade – people who sell guns and ammunition to anyone who is

prepared

to pay for them. But arms dealers are not the only offenders. Both governments and arms manufacturers make the money to develop their Star Wars weapons by selling armaments. We are disgusted at the thought of germ warfare, but rifles, like germs, spread the disease of war.

Some guns are now so light that children can handle them. Gabbin, at age eleven, could easily strip, clean and fire a Kalashnikov rifle. It looks like a toy, and weighs only 4.3 kilos, but yet it is capable of firing 600

bullets

a minute. Every day, children are taken from their families and taught to fight. There is nothing romantic about this. Children are often given a choice: kill your own parents or be killed yourself. If they do this, they are so torn by guilt and grief that they can be made to believe or do anything.

Crazed children, persuaded that they are invincible, are forced to lead

attacks

or even to walk through minefields.

The Cinnamon Tree

was written for you to enjoy. If, however, you would like to learn more, or do something about some of the issues raised in this book, these websites will give you accurate information:

1. The

International Campaign to Ban Landmines

(http://www.icbl.org)

is a network of organisations working for a Global Ban on Landmines. I was shown landmine clearance in Angola by

Norwegian People’s Aid

(http://www.npaid.no)

; similar work is being done by

MAG

(http://www.magclearsmines.org)

who are based in Manchester in the UK. Both clear and destroy landsmines and other unexploded weapons as well as assisting the victims.

2. You might be interested in raising money for mine clearance.

Adopt-A

-Minefield

is a wonderful scheme where large and small donations are

collected

to clear specific minefields. You can find out about the minefield you have adopted, see how the clearance is going, and how the people who were affected are getting back to normal lives

(http://www.landmines.org)

.

3. Perhaps you are interested in campaigning against the use of children as child soldiers. There are as many as 300, 000 children under the age of 18 serving in government forces or armed rebel groups. Some are as young as 8 years old. You can learn about these from

Human Rights Watch

(http://hrw.org./campaigns/crp/index.htm

).

The Coalition to Stop the Use of Child Soldiers

(http://www.child-soldiers.org)

works to prevent the use of children as soldiers. In my story Gabbin is lucky because he has a family to go back to. Most child soldiers find that nobody wants them when they give up their guns.

4. There is a very important campaign starting now to stop countries manufacturing arms and selling them to just anyone who will buy them. You can find out about

The Campaign Against The Arms Trade

at

http://www.realworld.org.uk/index.html

.

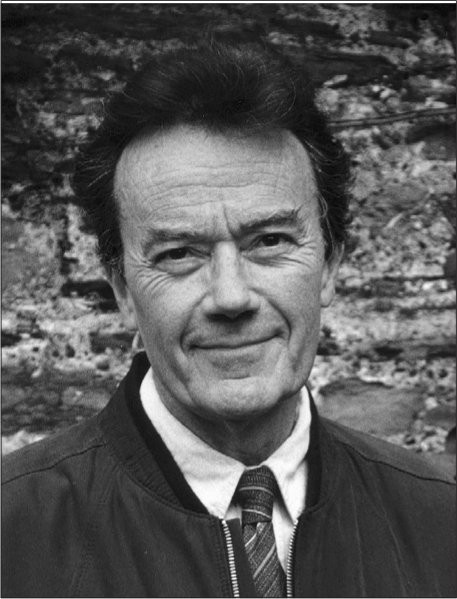

AUBREY FLEGG was born in Dublin and spent his early childhood on a farm in County Sligo. His later schooldays were spent in England, but he returned to Dublin to study geology. After a period of research in Kenya he joined the Geological Survey of Ireland; he is now retired and lives in Dublin with his wife, Jennifer.

His first book was

Katie’s War

, which won the IBBY Sweden Peter Pan Award 2000. It was followed by

The Cinnamon

Tree

. Aubrey then began the

Louise trilogy

, with

Wings Over Delft

, which won the Bisto Book of the Year Award 2004, Ireland’s most prestigious children’s literature prize, and is included in the White Ravens 2004 – a selection of outstanding international books for children and young adults made by the International Youth Library in Munich. The second part of the trilogy,

The Rainbow Bridge

, was published in 2004, and the third and final part,

In the Claws of the Eagle

, in 2006. Aubrey’s books have been translated into German, Swedish, Danish and Serbian.

This eBook edition first published 2012 by The O’Brien Press Ltd,

12 Terenure Road East, Rathgar, Dublin 6, Ireland

Tel: +353 1 4923333; Fax: +353 1 4922777

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: www.obrien.ie

First published 2000

eBook ISBN: 978

–

1

–

84717

–

490–1

Copyright for text © Aubrey Flegg

Copyright for editing, typesetting, layout, design

© The O’Brien Press Ltd

UNAUTHORISED COPYING IS ILLEGAL

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilised in any form or my any means, including electronic, digital, mechanical, visual or audio, or mounted on any network servers, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Carrying out any unauthorised act in relation to a copyright work may result in both a civil claim for damages and criminal prosecution. For permission to copy any part of this publication contact The O’Brien Press Ltd at [email protected].

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Flegg, A.M.

The cinnamon tree : a novel set in Africa

1.Land mines - Africa - Juvenile fiction 2.Children’s stories

I.Title

823.9’14[J]

The O’Brien Press receives

assistance from

Editing, typesetting, layout, design: The O’Brien Press Ltd

Front cover, background image: Angela Clarke

Front cover, photograph of girl: Corbis

Printing: Nørhaven Paperback A/S

D

ISCLAIMER

This book is a work of fiction. Characters, incidents and

names have no connection with any country, organisation

or persons alive or dead. Any apparent resemblance is

purely coincidental.