The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter (62 page)

Read The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter Online

Authors: Kia Corthron

Tags: #race, #class, #socioeconomic, #novel, #literary, #history, #NAACP, #civil rights movement, #Maryland, #Baltimore, #Alabama, #family, #brothers, #coming of age, #growing up

She dips a fry in her ketchup. And segregated. The sports league was very organized among the white clubs, national basketball championships. They would actively recruit black deaf players, offering them money or jobs, but refused to let them into the white clubs. And I'm not talking about the South. It happened in Detroit. It happened in New York! Then she sits back, a wry smile. Are you confused by my signs?

I tell her I don't understand her question.

Well! Plenty of white deaf have told me they're surprised when they

do

understand. That I'm the first black deaf person whose signs they can make out. Her eyes roll. They guess I went to Gallaudet, assume that's where I learned to sign white. But my family could always sign both ways. For a while I had to translate for another black student who was as baffled by the white signs as they were by his. She shrugs. They call white signs “standard,” but during the oralist movement, the white schools tried to force their students to speak while most black schools kept signing, black sign language was never interrupted so wouldn't that make it the purer language? Then April May June touches her thumb to her chin with her fingers outstretched, a fan comb pointing up. The sign for

motherâ

except she begins wiggling her fingers.

The black sign for

mother,

she informs me. Do you know the black sign for

color?

I shake my head, presuming it's not the gesture I recognize, wiggling fingers touching the chin. April May June lightly strokes her cheek with her index finger, and I see that in the Negro sign language

color

and

race

must be the same.

Of course, she continues, black signs vary state to state, county to county. She sips her root beer and asks about my interests, and I hesitate before mentioning my love of books, and the museum job, and the teaching, wondering if she will find me a great bore. She thinks the museum tours sound like fun (I only guide two groups a month) and the teaching job sounds rewarding (I'm only part-time).

Stop putting yourself down! Now, would you like banana cream pie? It's their specialty.

The waitress comes with the bill and I'm now seized by a new anxiety: Will she think I'm a chauvinist if I pay the entire check or a cheapskate if I suggest Dutch treat? I timorously take it, leaving a generous tip.

She smiles. Thank you. Next meal's on me.

At eleven we are strolling back to her apartment because she needs to pick up a book she promised to lend to someone at the party. As we cross Seventh Avenue, she remarks that when she entered Gallaudet in '55 it had only been four years since they'd started admitting Negroes. (Her term, as it has consistently been all evening, is

black,

but after my Alabama upbringing where even in my deaf isolation I was aware that

black

was considered a cruel insult, I'm still working to wrap myself around the new word.) My deaf university, she goes on, was established in 1864, a mandate of Abe Lincoln, but it took almost a hundred years for the Emancipation Proclamation to come to Gallaudet! She laughs, then goes on a light rant about the segregation of deaf schools reflecting that of the general public school system, separate and very unequal facilities, even in cases where the black and white children were on the same campus, and she details her own experiences at the South Carolina School for the Deaf and Blind and then asks, What was it like at Alabama?

I had promised myself I would be honest with her about this, though somehow I am still caught off guard when the moment is thrust upon me. My hands utter the words that have been on my mind all evening: I have never been to school.

She stares at me. I swallow.

I have never had any formal education. My brother. When I was a teenager, my younger brother taught me some signs, he taught me how to read. We took a short course on signs once, and I took more courses after I came to New York. Then my hands stop because there's nothing more to say.

But you teach. You lead art tours.

I'm self-taught.

She nods, not looking at me, absorbing the information.

I sigh. Well. It's getting late.

No it's not.

I thinkâ

Why do you want to leave all the sudden? You don't want to be friends with me because you find my formal education pretentious?

No!

She smiles. Good.

When we are just a block from her building, she turns to me: Tell me about your girlfriends.

I catch my breath. Naturally she notes my reluctance, and I hope she will take mercy on me and begin a new topic. I'm most comfortable when she's the one talking, which is usually, but she patiently waits for my response.

There's not much to tell.

There's

always

something to tell. I'll tell you about my boyfriends.

I look at her.

Nobody right now, she clarifies.

I look down. I stop walking. She stops walking.

I've never had a girlfriend.

She stares at me. Have you never been intimate with anyone?

I shake my head.

Her hands move gently. I was a late starter too.

Not

this

late.

She smiles again, and we continue walking to her place. Since you teach right here in the Village, you should stop by my place sometime after class.

When?

Surprise me.

Never.

She looks up.

You're inviting me to drop by uninvited, and that sounds like an invitation for trouble.

If I get sick of you, I'll just pretend I'm not home.

I'm not coming uninvited.

Then come Tuesday after your class. You're invited.

The paperback she came to pick up is on a small bookcase in her living room. It turns out she is also an avid reader, and we sit and begin to talk about Richard Wright and Hemingway, Salinger and Fanon, then civil rights and women's rights, Idi Amin and Vietnam and then she begins to kiss me and touch me and I'm awkward but I accept what she's offering and I watch as she effortlessly pulls out her couch into a made bed and she leads me to it and takes off my jacket and takes off her cardigan and unbuttons my shirt and caresses my chest and unbuttons her blouse and removes it and begins lowering my pants zipper,

Stop!

She stops. I'm panting panting.

I'm afraid.

She gazes at me, her smile surprised but tender.

That's alright.

We lie on her bed, eventually undress down to our underwear, and we hold each other, and we sleep. She never makes it to the party. In the morning, which neither of us remembers is Valentine's Day, she offers to make breakfast: Raisin Bran or Froot Loops?

By my definition, that night was the first time we made love, though we had not technically engaged in intercourse. That didn't happen until Tuesday after class.

Â

5

April May June is partial to the tapestries, but I'm captivated by the intricate ivory pieces on the subterranean level, breathtakingly detailed carvings of complicated, bustling scenes, an entire three-dimensional world inside a locket!

She took the IRT from the Village, the last car of the train as we'd agreed, and I joined her at Columbus Circle where we continued uptown to the top of Manhattan Island. A quiet Tuesday at the Cloistersâthe Medieval Art arm of the Metropolitan Museum, the structure resembling a castle. Perhaps because of its decentralized location, visitors are comparably sparse in striking contrast to the rest of the sardine city, the spaciousness luxurious and accentuating the hollowness of the edifice, its mystery. April May June's proofreading schedule is irregularâafternoons/evenings. Today she happens to have off, and my students are on spring break, my superintendent shift not till fiveâso we're fortunate to have this time, avoiding the gallery's somewhat more bustling weekend hours. April May June and I walk together and articulate our wonder. Sometimes we separate to have our own individual experiences, and from this I learn that we comfortably enjoy each other's company as well as our independence.

Afterward we stroll through the adjacent gardens. Little is in bloom so early in the season. The air is cool but we're fine in our spring jackets.

Yesterday was the Ides of March. She smiles as she tells me this, but I notice a vague despondency behind her expression, something I've sensed since we met today.

Is anything wrong?

No.

I perceive an ellipsis behind the sign. She sits on a bench. I sit next to her.

When I checked the mail on my way out to work yesterday, there was a rejection letter for my story. Her left foot is on the ground while her right foot faintly swings. I didn't open it till I got to work. I guess I didn't want to know. Or maybe I wanted to hold out hope it was good news long as I could. She kicks a stone. I should be used to it by now. Rejections are the only kind of mail I get.

I know that's not true. In the month we've been together she has received at least three letters from her sister Ramona and two from her mother. But I also know not to point that out just now.â©I would like to read your stories sometime.

She looks at me, then back at the patch of tiny wildflowers before us. The wind gently blows them. Something lavender.

They're not very good. Obviously.

I would like to read them.

They're not even fiction really. When I was taking that writing class, when we met? I told the teacher they were all true stories, I said I call them fiction but they're really autobiography. He had this knowing smile, he said, Yes, thinly veiled. After that I didn't come back to class. April May June pulls up her legs, sits with them crossed on top of the bench. I wouldn't be the first person to use personal anecdotes in fiction. I just wish I had more imagination. Especially since my thinly veiled autobiography apparently isn't very well written anyway.

April May June. My fingers rapidly spelling her full name, the appellation she has reserved for me alone, but before I can go on, her hands move again.

I half feel like an assimilator anyway, English isn't my first language, sign language is my first language, why'm I writing? I should tell stories in sign. She sighs. Two months ago I

did

get an encouraging rejection for the first time. They wouldn't publish the story but they liked a lot of it, please send more.

Did you send more?

I sent another the same day. I haven't heard anything yet. She plays with an ant in the dirt, repeatedly blocking its path with the toe of her sneaker. The letter I got yesterday said We've narrowed it down to seventeen hundred thousand submissions and yours didn't make the cut. It did

not

say We'd like to read more of your work.

I'm deciding whether I should ask for the third time to read her stories when her face changes, brightens.

Alright, enough feeling sorry for myself today. Let's catch the bus. I know a great burrito joint down on the Upper West Side.

**

April Fool's Day I stand perplexed in the gift shop of the new Studio Museum in Harlem. There's the book of photographs by Gordon Parks, and the book of paintings by Jacob Lawrence. April May June loves both artists. Would it be too extravagant, too forward in our relationship, to buy her both large volumes?

I need to get this shopping task behind me because tomorrow Ramona is coming, and April May June seems to have made many plans for all three of us so I'm not sure how much free time I'll have over the next few days. I'm terrified! We've only been together six and a half weeks. Isn't that early to be meeting family? I mentioned this to her a few days ago, trying to come off as joking but praying she would have mercy and suggest I wait until her sister's next visit. She replied with a smile that if I hadn't taken so long to write to her in the first place then we would have been together longer and I wouldn't be in this predicament now. She says that she's told Ramona all about me. I hope that's true because I couldn't bear the look of shock and disapproval on her sister's face were she to be confronted with unpleasant surprises. That I'm forty-seven. That I'm a janitor. That I'm white.

Late Friday afternoon I wait with April May June at Port Authority. I realize I've not been here, the arrival gates, since I first disembarked the bus from Alabama over a decade ago. I've never left the city. To go where?

Ramona comes flying into April May June's arms, the sisters embracing tight and joyously as if they haven't seen each other in twenty years. Same nose, mouth. Ramona a couple inches taller than her sister's five-five. She also sports an Afro, not quite as large as April May June's. A pink blouse and black slacks, differing from her sister's perpetual miniskirts. Ramona has playful eyes and now trains them on me, and signs: So this is B.J. We shake, and she shares her sign name with me: her first two right fingers crossed in an

R,

horizontally touching her cheek and twisting, similar to the sign for “candy.” When she smiles, I see why the sign was placed where it is: her dazzling dimples. Then she takes April May June's hand and subtly signs something to her I am not privy to. The sisters exchange smiles and I assume I've just successfully cleared some hurdle. We take the IRT to the Village. Ramona is starving and we find an Italian place. The sisters' hands are flying at lightning speed. I gaze at them, only half paying attention to their stories. There was certainly love in my own family, but never such an obvious manifestation of it.

After dinner I offer to carry Ramona's suitcase back to April May June's apartment but she waves off my offer, having traveled light for her week in New York, and then I leave them alone to catch up. April May June protests my early departure, but not too passionately, understandably wanting intimate time with her sister.

On Saturday while they're at the Museum of Modern Art, I do some cleaning of my apartment, not knowing if the Junes may surprise me with a visit. I meet them for an Italian dinner before we stroll to a theater on West 48th to see my very first Broadway show, a nineteenth-century play called

Hedda Gabler

. Ramona has splurged on the twelve-dollar orchestra seats and refuses to let me reimburse her. She sits between April May June and me, and our eyes flutter from the stage action down to Ramona's interpreting hands in her lap. A shocking story!

We go out for dessert, and April May June chats a bit regarding her curiosity about the recently established National Theatre of the Deaf. Directed and choreographed by hearers, the rapid movements, according to accounts she has read, are visually arresting but confusing for the deaf as there is no time allowed to properly understand the signs. The hearing, on the other hand, can use sound to keep abreast of the story. Ramona crinkles her nose to indicate she's listening but she's fading, having not slept well last night. You have no idea, she tells us, how loud this city is. Those damn sirens! Tomorrow I won't see the Junes as I will be on-call as the Sunday super.

Monday at eight, April May June pointedly reminds me. It will be her birthday, April 5th, my first party and this one I had better not miss.

Thank God I didn't come early, she remarks to her sister now.

You mean thank God you were a day late. You

were

supposed to be born on the 4th. It isn't until I leave them and notice a flyer for a prayer service in commemoration of the third anniversary of Martin Luther King's April 4th assassination that I realize what they were talking about.

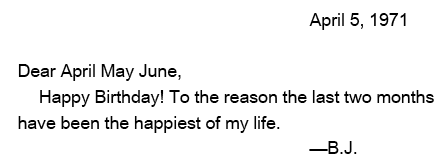

On Monday when I arrive at her Village townhouse, I'm the only guest. April May June admits that she knew I'd show up right on time before anyone else, having no concept of fashionably late, and Ramona, apprised of my punctuality habit, had discreetly waited until 7:50 to slip out and buy decorative flowers.

I miss you, April May June says, and for a while we kiss. Then I give her the presents, both art books, which she loves, and the card that I agonized over. I tell her she can wait until later to read it, and by this I mean

Please

wait until later to read it and she knows this and opens it anyway.

Â

Â

She stares at the words, and I can tell something doesn't sit well with her, but she forces a smile and says Thank you. This is exactly why I wanted her to open it later! It would put her on the spot for me to ask what's wrong.

Happiest.

Was that going overboard? Does she think I'm exaggerating? I'm not! Or does she believe me and that's what's making her uncomfortable? Or does she wonder, if I'm so happy then why didn't I sign the card with love? But isn't it too early for that? I don't know the rules!

Ramona, who's gone so long I think she must have planted and cultivated those chrysanthemums, finally returns to find April May June and me awkward and relieved by the interruption. At quarter to nine a few guests arrive, and by ten the place is packed by people of various races, most in their late twenties or thirties, the apartment smoke-filled which April May June apparently tolerates for the sake of the occasion. Most of the crowd are deaf but there are a handful of hearers talking in a corner. Many of the invited make a point of greeting me, and their smiles imply whatever April May June told them about me must have been good. I'm grateful for their sociability because otherwise my impulse would be to take my champagne glass and sit alone in a corner, my shyness possibly mistaken for snobbery. April May June has guests flocking her all evening, in addition to the deaf the good hostess taking time to speak verbally with her hearing friends while periodically sending glancing smiles in my direction.

She has insisted on all thirty-four candles, claiming if she blows out any less she won't get her wish. We sign the birthday song while the hearers sing, and afterward, eating my chocolate cake, I realize how sleepy I am. Ten forty-five, and I'm ordinarily in bed by ten, so here's the next dilemma: If I'm April May June's “steady,” is it improper for me to leave earlier than everyone else? As if in answer to my prayer I feel someone coming from behind, slipping her arm in mine.

Tired?

I smile, so grateful for this touch.

Go home, go to bed. Would you like to come to the movies with us tomorrow?

Yes.

An American movie! With familiar New York scenes! Ramona sits between us again, interpreting. The film is called

Shaft,

and though I'm not partial to the action genre, it's thrilling to enjoy a contemporary film from my own country, even this somewhat outlandish representation. The sisters appreciate the racial truths, find the drama intermittently silly, and love it beginning to end.

After the movie we sit in a diner, Ramona and I saying our goodbyes. Tomorrow morning she and April May June will take the train upstate to see an aunt, and Thursday, Ramona's last full day before catching the bus early Friday morning, the girls plan to visit a few tourist sites. April May June has clarified to me in no uncertain terms that it is no longer proper to refer to grown women as “girls,” and I agree with her, but I must admit, in observing them, this is the word that keeps popping into my mind: the way they smile and hold secrets like teenagers. In the booth they are side by side across the table from me.

And I wanna get a picture of the skyline, Ramona tells her sister, who is detailing their upcoming sightseeing agenda on a napkin.

You came right as it's changing, April May June remarks. Construction's just finishing on the second of the two World Trade Center towers, supposed to be done in the summer. They surpassed the Empire State Building. World's tallest.

Ramona turns to me now. I'm so happy we met, B.J. The warmth in her eyes tells me she's sincere.

I hope you come back again soon, Ramona.

The Brooklyn Promenade's probably the best view of Manhattan, right? April May June asks me. How do we get there again?