The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter (61 page)

Read The Castle Cross the Magnet Carter Online

Authors: Kia Corthron

Tags: #race, #class, #socioeconomic, #novel, #literary, #history, #NAACP, #civil rights movement, #Maryland, #Baltimore, #Alabama, #family, #brothers, #coming of age, #growing up

I scratch a brief note, bequeathing my only treasure, my books, to the public library. Had I any other valuables there'd be no one to will them to anyway. A nagging sense of responsibility drives me to investigate the wreckage in the lobby, to make sure the ceiling isn't about to all come bursting down. I walk down the stairs. It will withstand the night. I would go ahead and repair it now, leaving no unfinished business, but I can't make an official decision on a public space without Lloyd's say-so.

I glance at the mailboxes. In all the excitement I had forgotten to check my mail, as if it would be anything other than an advertising circular.

I stare, my heart thumping. A personal letter. I take it out.

The exact same letter I'd sent to my mother six weeks ago, but now with a special stamp by the post office:

DECEASED

.

RETURN TO SENDER

.

Â

4

I have no idea how long ago my mother died but for me it just happened and I weep, my body violently convulsing with the torrent but I'm silent: a deaf person learns early on the awkward and unfriendly looks his utterances can attract and thus perfects the art of soundless emotion.

Would it have been so painful to have mailed an occasional postcard, just to have kept her apprised of my whereabouts? Even if she refused to respond immediately, she may have thought differently later. Why couldn't I have been loving son enough? Man enough? If she never answered, at least I would have been at some peace knowing I'd tried. For all she knew I could have been dead. And might this stress have contributed to her own passing?

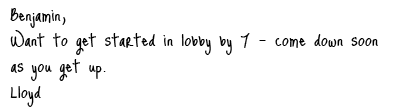

At 1 a.m. I glimpse a note being slid under my door.

Â

Â

I'm ordinarily off Saturdays, but this task is definitely classified under the emergency on-call feature that's part of my job description. I don't sleep and at 6:30 start to force myself calm, at seven leaving my apartment. Lloyd is not in the lobby so I knock on his door, and when there's no reply I knock harder. He wakes, and by 7:15 we begin the formidable chore. An all-day job and, against union rules, I work through lunch as I fear a break could catapult me into another sobbing episode from which I may not easily recover.

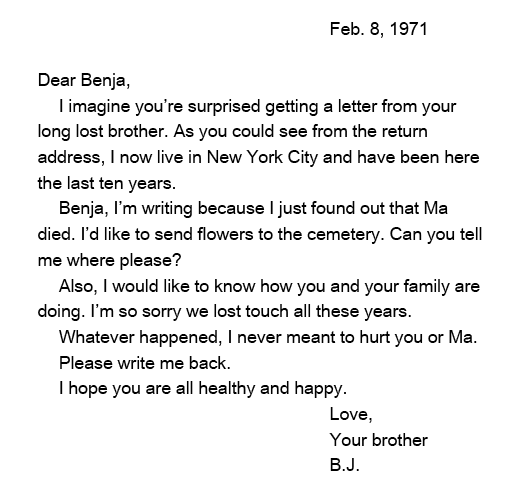

Seven in the evening, the work completed, I lie on my bed. I should write to Benja. I need to know the cemetery, where to send flowers. And when did she pass on. And was she at all happy those last years? And are

you

alright, sister? And your children? My Lord, the oldest must have graduated by now and suddenly it comes flooding back, the last time I'd seen her, barely healed from the pounding her husband had given her and when I'd seen

him

last I'd just removed the bullets from his pistol. What happened after he bought more and reloaded?

I fall into an anxious sleep, waking at 4:30. I throw on a couple sweaters and walk hours in the predawn darkness. I wind up at St. John the Divine as the doors are opening for the day, and I enter, sit in a pew, not knowing what to pray for but I missed my mother's funeral so this is the place I believe I should be now. Twenty minutes later my solitude is broken by an influx of congregants, and I remember it's Sunday and early morning services will start soon. In the neighborhood I discover a thrift shop and stop in to buy a used coat. Walking home the seventy blocks I begin to feel dizzy, and by the time I step into my building I have fever and chills. I go into the bathroom to splash my face and am taken aback to see Ma staring at me from the mirror, how much I have come to resemble her with age. I have occasionally pondered that I have not inherited even one of my poor father's physical features. I shake my head. What's the difference? He fed me and clothed me, and the rest was the business of him and my mother.

I realize I haven't eaten since lunch yesterday and check to see if there's any canned soup in the kitchen, where I find the pitcher of dissolved pills right where I'd left it. I'd forgotten. And if I hadn't, how selfish to have killed myself rather than to have given my mother her proper mourning. Only now does it occur to me: How would my young students have taken my self-inflicted demise? I'll have to remember for the future that no matter how alone you are, you cannot escape affecting others. If I ever make this decision again, I'll be considerate enough to plan it during a summer break. I pour the concoction down the sink.

I turn in early, and when I wake in the morning I'm still a bit light-headed but strong enough to hold a pen.

Â

Â

Tuesday morning I feel somewhat better, and I walk down to see how the lobby ceiling is holding up. It's fine, but I'm reminded about the broken entrance door lock, something I'd mentioned to Lloyd Saturday and which he should have repaired yesterday. I walk up to his apartment. He shrugs and says he needs special parts and has sent away for them. I'm not sure he's telling the truth. An hour later I commence the fifty-block walk to my classes and when they are through I walk the fifty blocks home, not certain why since the news of my mother's passing I keep choosing my feet over the subway. I step through the unlocked outside door and open my mailbox, pulling out the drugstore circular. I'm surprised to see a personal letter behind it, no name, only the return address. I recognize it instantly.

Â

Â

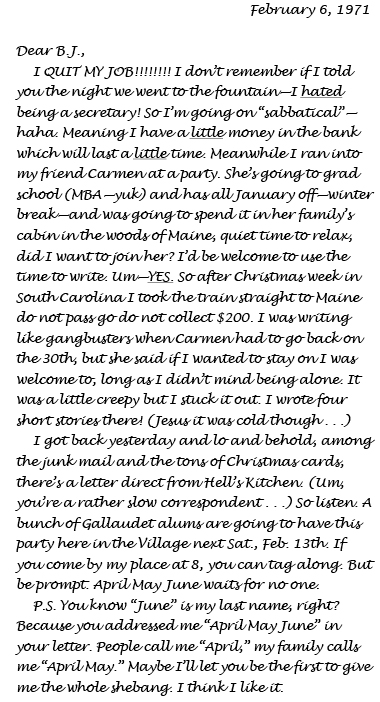

Terrified of train delays, I am waiting for the IRT at seven and standing in front of April May June's townhouse at 7:25. I was afraid to walk and build up a sweat even bigger than my nervousness already has. She may not be pleased to have me here this early, so I stroll around Greenwich Village checking my watch every two minutes.

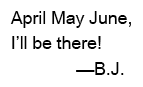

Her letter arrived on the 10th, giving me only three days' preparation. Though the only reply it had called for was my showing up tonight or not, I was so worried she may get the wrong idea that I wrote back immediately.

Â

Â

After mailing it, I fretted that its delivery may be somehow delayed. I considered sending a second note,

Â

Â

but feared if she got both messages she may think I'm a lunatic.

And while receiving her letter was the single happiest event of my New York life, I was racked with trepidation regarding this party. My only comparable experiences were childhood birthday celebrations with my family. I had requested tea, a one-on-one with her, not a roomful of people. But of course after my long silence she couldn't be sure she could trust me. If she invites me to accompany her to a party and admonishes me to be punctual or she'll leave, then if I don't show she wouldn't feel stood up, or not

very

stood up, having arranged that me or no me she has social plans for Saturday night.

At 7:55 I stand outside April May June's four-storey building and try not to panic as I wonder how I will summon her. It's a quiet street, no one going into her building to whom I could pass a note to slip under her door. Not knowing what else to do, I push the buzzer. To my surprise, lights flash on the top floor. She comes to the window and waves, then signs something but it's too dark to see. A few moments later she opens the outside door, smiling. She looks very pretty in her miniskirt, and seems to have spent time on her cosmetics. I wonder if I have dressed properly, the secondhand pinstripe suit I purchased for the occasion, not knowing who to consult on these matters. She takes the flowers I have brought, and invites me up.

Her studio apartment is neat, clean, a bit cluttered. Used furniture, hanging beads. She signs Goodwill was her decorator. I realize since coming to New York I have never been in another person's home, unless it was because I was asked to fix the toilet or radiator. I tell her it's a very nice place. She smiles and signs, Rent-controlled. A long-haired gray cat appears.

That's Mr. Peoples.

She asks me to sit while she goes to the bathroom to apply her lipstick. When she returns, she sees I have unbuttoned my suit jacket in her warm flat, though not taken it off.

My, you're formal.

I look to the floor, embarrassed that I have apparently made the wrong fashion choice, assuming this will embarrass her. I feel her coming closer to the couch and I look up.

What's wrong.

I hesitate.

I've never been to a party.

Never?

I shake my head.

Are you looking forward to this?

I'm looking forward to spending time with you.

She sits on the green soft chair, taking me in.

Would you rather not go?

They're your friends. You'll have a good time.

Would you rather not go?

I sign No, then I sign Yes.

Have you had dinner yet?

I shake my head, hopeful.

That party will go on till the wee hours. What if we eat now, then I can go on and you can come with me, or not. Up to you.

I nod, so grateful!

Diner okay?

We have burgers and fries and I worry her food will get cold as her hands chatter on, but I take in all she's saying, it's only with enormous effort that I don't constantly smile. She tells me she was able to secure another proofreading job, children's textbooks. She speaks about growing up with deaf parents and mostly deaf siblings. I wonder to myself what it must have felt like, to have been raised in a family and not felt so alone, within it and outside of it at once. I tell her I'd never heard of genetic deafness until she described her heritage, that I have since been researching it. She speaks of the phenomenon, not an especially rare one, then mentions a Georgia clan, two parents and twelve kids, all deaf. We knew them from the Atlanta deaf club, she says, which was the closest black deaf club to us. I have no idea what she's talking about but, afraid she'll think of me as a complete bumpkin to all things deaf, I try to conceal my mystification.

You don't know about deaf clubs?

Feeling my blush, I shake my head.

Cultural centers. Play performances and sports teams, card playing. Job recommendations. Sprang up during the forties, when people congregated to cities hiring deaf for the factory jobs the hearing men left when they were sent off to Europe or the Pacific. So the clubs were mostly blue-collar.