The Café Spice Cookbook: 84 Quick and Easy Indian Recipes for Everyday Meals (6 page)

Read The Café Spice Cookbook: 84 Quick and Easy Indian Recipes for Everyday Meals Online

Authors: Hari Nayak

Tags: #Cookbooks; Food & Wine, #Cooking by Ingredient, #Herbs; Spices & Condiments, #Quick & Easy, #Regional & International, #Asian, #Indian

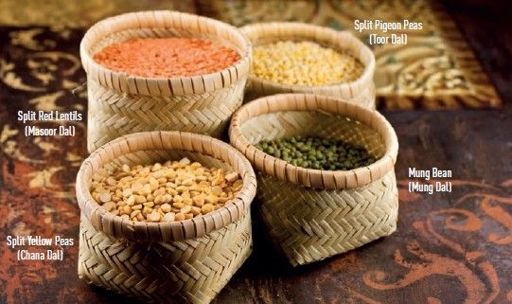

Dried Legumes (Lentils, Dried Beans, and Peas)

In India, all types of dried legumes—be they lentils, peas or beans—are known as

dals

. They are an integral part of Indian meals, being economical; highly nutritious; very low in fat; and a good source of carbohydrates, proteins, fibers, minerals, and vitamins. Dals are a good substitute for meat, which has more fat and cholesterol. Many common varieties of dals, such as chickpeas (

kabuli chana

), kidney beans (

rajmah

), whole green lentils (

sabut moong

), and cow peas (black-eyed peas) are available in conventional supermarkets. Some not-so-common varieties used in Indian cooking include pigeon peas (

toor dal

), split black gram, aka “black lentils” (

urad dal

), split green lentils (

moong dal

), split red lentils (

masoor dal

), and split yellow peas (

chana dal

). For these, a trip to an Indian grocery store or an online purchase is necessary (see Shopping Guide, page

140

).

Dal dishes come in various forms—thin and soupy (South Indian Lentils and Vegetables, page

56

), thick and creamy (Homestyle Dal with Pumpkin, page

60

), and hearty and comforting (Chickpea Curry with Sweet Potato, page

54

)—and may be the basis of a salad (Chickpea, Mango and Watercress Salad, page

45

).

There is nothing more comforting and soulful than a bowl of dal topped with some steamed rice. I incorporate dals into my everyday meals—both Indian and non-Indian. I cook my dried legumes the old fashioned way in my kitchen, using a pressure cooker. Though this technique is not so popular in North American and Europe, I urge you to give pressure cooking a try: It uses less liquid, has faster cooking times, and the food retains more vitamins and minerals. I can assure you that once you get used to a pressure cooker, you will be eating more dals as part of your daily meals, especially the longer-cooking types. Anticipating that not everyone will have a pressure cooker or be inclined to use one, the recipes in this book call for common kitchenware, such as saucepans or pots. If you want to experiment with a pressure cooker, simply follow the instructions provided with it; you will find that cooking time is reduced by more than 50 percent!

I often stock my pantry with canned legumes, which I find to be an acceptable substitute for dried, and very convenient when I’m in a rush. For the dal recipes in this book, I include the option of using commonly available canned peas or beans. Make sure to drain and rinse them thoroughly before using them.

Fennel Seeds

These are the oval, pale greenish-yellow seeds of the common fennel plant, a member of parsley family. They are sweetly aromatic and have an anise-like flavor. In Indian cooking, they are used whole and ground in both sweet and savory dishes. Roasted fennel seeds are sometimes sugarcoated and chewed as a digestive and mouth freshener after Indian meals. They are readily available in most grocery stores.

Fenugreek Leaves

Known as

methi

when fresh and

kasoori methi

when dried, these leaves are extensively used in Indian cuisine. The slightly perfumed and bitter flavor of the leaves goes very well with curries. The leaves are sold fresh when in season or dried in packets year round in Indian markets. The dried leaves can also be purchased online (see Shopping Guide, page

140

). Frozen chopped fenugreek greens are also now available at some Indian grocery stores. I use the dried version—kasoori methi—in the recipes in this book because of its unique flavor and strong taste. In comparison, fresh methi (young leaves and sprouts of fenugreek) has a very mild flavor. When fresh, the leaves are eaten as greens and are commonly cooked with potatoes, spinach, and paneer and eaten with

roti

or

naan

(breads). The dried leaves have a bitter taste and strong aroma and are used in small amounts to flavor dishes. There is no real substitute for this ingredient in Indian recipes, and so I have made its use optional throughout the book.

Fenugreek Seeds

The fenugreek seeds are bitter, yellowish-brown, tiny seeds that provide commercial curry powders their distinctive aroma. They are used in small quantities because of their strong flavor. In the southern part of India, the seeds are often oil-roasted and then ground to create a bitter balance in curries; in eastern India, the seeds are stir-fried whole. They are available only in Southeast Asian or Indian grocery stores.

Garlic

A close relative to onions, shallots, and leeks, garlic has been used throughout recorded history for both culinary and medicinal purposes. It has a characteristic pungent, spicy flavor that mellows and sweetens considerably with cooking. Garlic powder is not a substitute for fresh garlic in traditional Indian cooking. Whole bulbs of garlic will keep for several months or more when stored at room temperature in a dry, dark place that has ample air circulation. Keep in mind, however, that garlic’s shelf life decreases once you start removing cloves from the bulb. Storing garlic uncovered, such as in a wire-mesh basket inside your cupboard is ideal. You can also store garlic in a paper or mesh bag. Just be sure there is plenty of dry air and little light to inhibit sprouting. To avoid mold, do not refrigerate or store garlic in plastic bags.

Ginger

A knobby, pale-brown rhizome of a perennial tropical plant, ginger is available fresh, dried, ground into a powder and as a preserved stem. Ground ginger or preserved ginger is almost never used in Indian cooking. Fresh ginger root has no aroma, but once you peel or cut it, it emits a warm, woody aroma with citrus undertones. When used fresh, it has a peppery hot bite to it. Fresh ginger is used throughout India and is a very common ingredient in Indian cooking. It is often ground into a paste, finely chopped, or made into juice. We use chopped ginger to stir-fry vegetables, crushed ginger or ginger paste in meat stews and legumes, and thinly sliced slivers of raw ginger to sprinkle over curries just before serving. While shopping for fresh ginger, look for a hard and heavy root that snaps easily into pieces. Avoid dry, shriveled roots that feel light for their size. Keep fresh ginger in the refrigerator crisper in a plastic bag with a paper towel to absorb moisture (to prevent mold, change the towel occasionally). The root will last for two or three weeks. To extend its life, you can freeze ginger. You don’t even need to defrost it, and ginger is much easier to grate when frozen.

Ghee

This is the Indian version of clarified butter—that is, butter from which milk solids are removed. Ghee is one of the primary cooking fats used in India. Unlike regular clarified butter, the process of making ghee involves melting the butter over a low heat and then simmering it until all the moisture has evaporated, and the milk solids have separated from the fat. The milk solids are then removed, leaving a pure fat that is excellent for deep-frying because of its high smoke point. I just love the way ghee infuses food with a delicious flavor and aroma. It has a buttery and a nutty flavor. I often add a few drops to hot rice dishes, dals, and curries as finishing oil. Ghee has a very long shelf life and at room temperature will keep for 4–6 months. Store it in a clean, airtight plastic or glass jar. Ghee is commonly available in Indian grocery stores and is typically sold in glass or plastic jars as a solid, butter-like fat. In many recipes in this book, I have called for ghee, which I feel brings out the best flavor of those dishes. If you do not have ghee, substitute a mixture of equal parts of unsalted butter and neutral-flavored oil.

To Make Ghee at Home:

Melt 1 lb (450 g) of unsalted butter in a heavy-bottomed, medium-size saucepan over medium-low heat. Simmer, stirring occasionally, until the milk solids turn a rich golden color and settle to the bottom of the pan, about 15–20 minutes. Initially, the butter will foam and as it simmers the foam will subside. Pass the mixture through a fine-mesh strainer lined with cheesecloth or muslin into a sterilized jar. This recipe makes about 2 cups (500 ml) of ghee. Note: Use either one 12-in (30-cm) square piece of fine muslin or four layers of cheesecloth.