The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows (15 page)

Read The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

BOOK: The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows

7.19Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

“You know about that?” asked Olive.

Annabelle blinked, hesitating for a split second.

Then she said, “I could hear the commotion all the way up here.”

“But I didn’t want the dog to come out. He was chasing one of the cats.”

Annabelle’s eyes glowed. “Yes, a cat. But you untied the dog. You set him free.” She looked at Olive closely, her eyes like two gold candle flames. “I helped you, and now you can help me. Isn’t that what friends do? Will you set me free, Olive?”

Annabelle held out her hand. Olive took it. It was very smooth and pale, and very, very cold.

Annabelle stood up. She smiled. “I haven’t left this room in seventy years,” she said. She climbed onto the couch and sat, sidesaddle, on the picture frame, still holding Olive’s hand. Then she swung her legs gracefully through. Olive hurried after her.

16

I

T FELT FUNNY, walking through the house with a person who hadn’t been there at all—not really—just a few minutes before. Olive glanced up at the young woman next to her, with her carefully combed brown hair and pearls and long gauzy skirts. She felt as though a princess in one of her fairy tale books had climbed out and was waiting to be shown around the house. Except, of course, that Annabelle knew her way around.

T FELT FUNNY, walking through the house with a person who hadn’t been there at all—not really—just a few minutes before. Olive glanced up at the young woman next to her, with her carefully combed brown hair and pearls and long gauzy skirts. She felt as though a princess in one of her fairy tale books had climbed out and was waiting to be shown around the house. Except, of course, that Annabelle knew her way around.

At every doorway, at every picture and piece of furniture, Annabelle paused. “It is so good to move around this house again,” she said. “I have missed it so much. My house. My old home.”

My

house, thought Olive, but she didn’t say this out loud. It was so good to have company, she didn’t want to start an argument.

house, thought Olive, but she didn’t say this out loud. It was so good to have company, she didn’t want to start an argument.

In front of the painting of the forest path, Annabelle stood looking for so long, smiling and not saying anything, that Olive began to get anxious. Then Annabelle shook her head, as if she was clearing a thought away. “I’m sure we’ll find my necklace,” she said. “I can tell that it’s nearby.”

After they had walked all around the upstairs, Olive led Annabelle toward the first floor, but they never made it. Annabelle stopped with a gasp halfway down the stairs.

“There,” she whispered. “There—I remember that place. That is where I left it.”

Olive looked back. Annabelle was pointing at the painting of the silver lake—to the very spot where Olive had first seen the necklace. Olive could feel her heart starting to pound against her rib cage. Part of her wanted to pull out the necklace, offer it to Annabelle . . . but another part of her said no. It said no very, very loudly. And what had Horatio told her? That she shouldn’t show the necklace to

anyone

. Besides, she couldn’t take the necklace off. What would Annabelle do if she realized that her precious lost present was stuck around Olive’s neck?

anyone

. Besides, she couldn’t take the necklace off. What would Annabelle do if she realized that her precious lost present was stuck around Olive’s neck?

“Put on the spectacles, Olive,” said Annabelle. Olive’s hands obeyed, even though Olive’s head didn’t want to. Annabelle took Olive’s hand, and again Olive noticed the icy cold of Annabelle’s touch. With Annabelle leading the way, they climbed into the picture of the silvery lake.

Annabelle headed toward the water, her tiny pointed boots making sharp prints in the sand. Olive stumbled behind her. The ripples in the lake seemed to get rougher, wilder, as they approached.

Annabelle stopped at the shore. She glanced up and down the beach, where the lake had scattered small red and black stones, and looked into the water. “I think it is a few feet farther out in the water,” she said to Olive without turning. “There is an old rowboat in the reeds over there. Get it.”

Olive looked where Annabelle was pointing. To her surprise, there was a weathered wooden rowboat half covered by the waving reeds. She hadn’t noticed it before. Olive dragged the boat along in the shallow water until it stood in front of Annabelle. Annabelle climbed in first, taking up the oar, and Olive climbed in after her.

Annabelle began to row. For a delicate-looking woman, she rowed powerfully.

“Do you see anything?” asked Olive, peering out into the water.

“Not yet,” said Annabelle.

They were quickly beyond the shallows, but Annabelle kept rowing. Soon they were ten feet, twenty feet, fifty feet from the shore.

“I can’t see the bottom anymore,” said Olive nervously. “Do you think the necklace is out this far?”

This time Annabelle didn’t answer. She rowed farther into center of the lake. Here the water no longer looked silver, but black, and the evening sky above looked cold and distant.

“Would you like me to take a turn rowing?” offered Olive, trying to keep the tremble out of her voice.

“I don’t think so,” said Annabelle. Then, as Olive watched, Annabelle hurled the wooden oar far out into the water. The waves were choppy now, and the oar bobbed and flickered in the ridges, moving farther and farther away.

“You see, I know where the necklace is,” Annabelle said softly, giving Olive the tiniest of smiles. “I knew even before you let me out of my portrait.”

“You did?” Olive gulped.

“Yes. I’ve been watching you. You’ve been in and out of paintings all over this house. Sometimes you’ve only gotten in the way—like when you took that little boy back out of the forest. But other times you’ve done just as we wished, like setting the dog loose. And letting me out.” Annabelle leaned closer to Olive. Her voice was low. “And I know something else. I know that you can’t take the necklace off now that you’ve put it on. That’s how it works. You will wear it until you die.”

“Until you die?” Olive whispered.

“Not me,” Annabelle said. “I’ve already died.

You

.”

You

.”

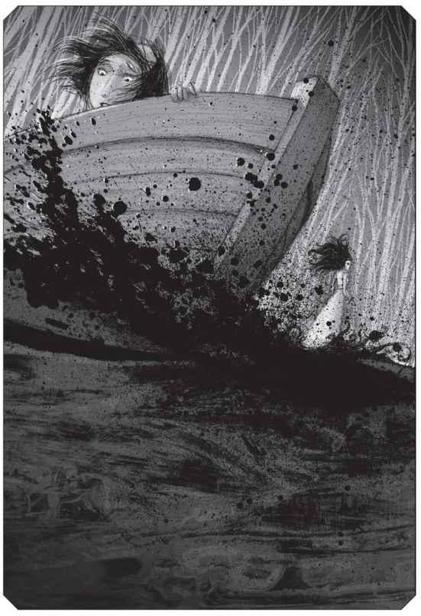

Annabelle stood up. The boat rocked crazily. The waves plunged and rose. And then Olive saw something she had seen twice before—a thick, black shadow, pouring across the sky like oil, turning everything beneath it cold and dark.

Annabelle raised a hand. Between the rowboat and the shore, a path of smooth black stones appeared on the water. Annabelle stepped out onto the path, making her way gracefully toward the land. The stones dissolved into the water behind her.

She glanced back once at Olive, who was clinging to the side of the boat in the roiling black water. “Good-bye, Olive,” she said. “Someone should have told you not to take things that don’t belong to you. Speaking of which . . .” Annabelle made a sign in the air. Olive felt a wind as strong as a fist hit her rib cage. It ripped the spectacles from around her neck, carried them through the air, and dropped them into Annabelle’s waiting hand. Then Annabelle walked to the end of the path, onto the shore, and into the darkness.

A large wave lifted the rickety little boat. For a second the boat hovered there on the crest of the wave, and Olive had the chance to look around at the shining, splashing darkness. Then the boat plunged back down the wave’s other side, dragging Olive—and, a second later, Olive’s stomach—with it.

She hung on to the slippery wood with both hands. “Help!” she yelled to nobody at all. “Help me!”

A flood of cold water splashed over the low sides, leaving Olive drenched. The wind was growing stronger, the waves were getting higher, and Olive was quite sure that she was screaming, even though she couldn’t hear her own voice.

Another wave pummeled the boat’s side. Olive braced herself against the boat’s low walls, trying to balance it with her weight, but when the next huge wave crashed into the boat, Olive was tossed out of it like one noodle slipping out of a spoon and landing back in a huge bowl of soup.

For a few seconds everything was black. Black, and cold, and

wet

. Olive realized that she was beneath the murky water of the lake, but with the darkness solid as marble on every side, she had no idea which way was up. Even with her eyes wide open, she couldn’t see a thing. This was probably for the best, Olive decided—she didn’t want to know just what else might be swimming beneath her in the black water of the lake.

wet

. Olive realized that she was beneath the murky water of the lake, but with the darkness solid as marble on every side, she had no idea which way was up. Even with her eyes wide open, she couldn’t see a thing. This was probably for the best, Olive decided—she didn’t want to know just what else might be swimming beneath her in the black water of the lake.

Her lungs were already starting to ache. Olive made her body go limp, hoping she would float to the surface like a bubble. Sure enough, she felt herself being pulled very slowly in one direction. Olive kicked her legs, paddling wildly, her lungs threatening to burst—and then she was breaking through the surface, taking in huge gulps of air.

The lake was still rocking like an overcrowded trampoline. Olive, struggling to keep her head above the water, was hoisted and dropped by rows of waves. She squinted through the darkness. There—in the distance—she could see a small square of light, where the picture frame held a lamplit view of the stairs.

Olive began to paddle toward it, holding her breath whenever the waves crashed over her head. Once or twice, she swallowed a mouthful of lake water. It was mucky and oily, and tasted like molding leaves. The frigid water was turning her feet numb. She was exhausted; her arms and shoulders ached, but the little square of light was coming closer.

A towering wave smacked her like a swatter landing on a housefly. The force of it pushed her down under the surface, but this time, Olive felt her feet touch the rocks at the bottom of the lake. She gave a strong push with both legs. Soon she was paddling, then crawling, onto the wet sand of the shore.

Olive knelt there for a moment, panting and gasping. Then she took off at a run for the picture frame.

“Somebody!” Olive yelled. “Anybody! Help me!” The shadows in the sky pulsed and thundered above her. Olive could hear the darkness roaring all around; she could feel it, grasping at her arms and legs, trying to pull her back. Olive glanced down at the shadows sweeping around her body. Was she imagining it, or were her feet changing color? Yes—they looked grayer, and different, somehow. They were streakier. Shinier. They looked like they had been made of paint.

With a rush of nausea, Olive realized what Horatio had meant about being trapped in the painting for too long. He had been telling the truth after all. Was this what had happened to Morton? And to the neighbors? And to the men who had laid the gravestones in the basement? Revelation pummeled Olive like another great black wave. Maybe the cats had been telling the truth the whole time. And maybe it was already too late.

Olive clamped her hands around the silver edges of the frame. “Horatio!” she screamed. “HORATIO!”

“Well, back up if you want me to get in there,” a voice snapped.

Olive staggered sideways, and the huge orange cat soared through the frame. Horatio glanced up at Olive through the dark, swirling air, and the irritated expression on his face disappeared for a split second. “Are you all right?” he shouted over the storm.

“Mostly. My feet—” Olive looked down. The shiny streaks of paint had climbed past her ankles. Her toes felt numb.

“Hang on to my tail! Hurry!” Horatio bounded back through the frame.

Olive locked one hand around Horatio’s tail and the other around the picture frame, hoisted herself out of the painting, and shot across the hallway stairs with such force that she hit the opposite banister and rolled all the way down the steps onto the rug at the bottom of the staircase.

Olive pulled herself up onto her elbows and examined her legs. Little tickling waves of warmth were zinging down from her knees to the tips of her toes. If she hadn’t known better, Olive would have thought her legs had fallen asleep. Her feet looked like they had always looked, like they were made of bones and skin. She wiggled her toes. So far, so good.

Horatio huffed and paced on the step above her. “What did I tell you?” he demanded. “I said,

Don’t lose the spectacles

. I said,

If you lose them, you won’t be able to get out again

. For more than a century, nobody lost those spectacles. But

you

manage to lose them in just a few weeks and to almost get yourself killed because of it. It’s astonishing, really. The

one thing

I’ve told you to do, the most important thing—”

Don’t lose the spectacles

. I said,

If you lose them, you won’t be able to get out again

. For more than a century, nobody lost those spectacles. But

you

manage to lose them in just a few weeks and to almost get yourself killed because of it. It’s astonishing, really. The

one thing

I’ve told you to do, the most important thing—”

“But I didn’t lose them!” shouted Olive, who had finally gotten her breath back. “She took them.”

“She?” Horatio crouched on the step, staring intently at Olive. “She who?”

The doorbell rang.

Horatio bolted up the stairs. Olive clambered to her feet, which still felt a bit numb, and pushed the wet strands of hair out of her eyes. Her saturated sweat socks made small

squish, squish

sounds as she walked along the hall to the door.

squish, squish

sounds as she walked along the hall to the door.

Other books

Landfall: Tales From the Flood/Ark Universe by Stephen Baxter

Balance of Power by Stableford, Brian

Californium by R. Dean Johnson

The House on Hancock Hill by Indra Vaughn

ARC: The Wizard's Promise by Cassandra Rose Clarke

City by Alessandro Baricco

Un milagro en equilibrio by Lucía Etxebarria

Running Back by Parr, Allison

Feed by Grotepas, Nicole

Frost Like Night by Sara Raasch