The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows (11 page)

Read The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows Online

Authors: Jacqueline West

BOOK: The Books of Elsewhere, Vol. 1: The Shadows

5.59Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The floor of the lake felt oozy and slick. She touched a few things that were absolutely not alive anymore, and a few things that might still have been, and then she touched something smooth and solid—something that felt like metal.

Olive popped back out of the water like a cork, holding tight to her prize. In the painting’s dim evening light, it was hard to see, but the thing in her hand looked like a necklace. It had a long, delicate chain and a smooth gold pendant shaped like an egg. Little swirls and curlicues were etched in the metal. Olive draped the chain around her neck and trudged toward the shore, looking down at the necklace so intently that she didn’t notice the fluffy orange cat until she had nearly stepped on him.

Horatio leaped back with a yowl as Olive, and a great deal of lake water, headed onto the sand.

“I’m sorry, Horatio. I didn’t see you.”

“So I noticed,” said the cat. “What have you got there?”

Something in the cat’s suspicious green eyes compelled Olive to lie. “Nothing,” she said, hurriedly dropping the pendant down the inside of her shirt.

“Nothing. Hmm. Very convincing,” said the cat, watching skeptically as Olive struggled to pull her socks over her wet feet. “I’m sure, given a bit more time, you would have come up with something even more stunningly believable.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” said Olive.

“Yes, well—that probably

is

true much of the time, but I’m surprised you want to admit it.”

is

true much of the time, but I’m surprised you want to admit it.”

Olive crossed her arms and glared down at the cat, whose fur gleamed like bronze in the painting’s violet light. “I don’t have to tell you everything.”

“No, you don’t,” said the cat. “But it would be a great deal easier if you did.”

“Easier? I haven’t been able to find you for days! Besides, I know you’re keeping secrets from me. Why shouldn’t I keep them from you?”

“Because I know what is best.”

Olive squeezed a dribble of lake water out of her hair. She was getting a bit chilly in her wet clothes, and more than a bit sick of Horatio’s unhelpful answers. “A cat knows what’s best for me?”

The big cat narrowed his eyes. “I am doing my best to protect you. And, by the way, you’re not doing much to make the job easier.”

“It’s your job to protect me?”

“You, and the main floors of this house. Leopold, whom you’ve met, protects the basement. And . . . someone else protects the attic.”

“Oh, I see. That makes perfect sense—cats protecting a house.”

“If you hadn’t noticed,” Horatio enunciated, “we’re not exactly ordinary cats.”

“So just what are you protecting the house

from

? Besides mice, I mean.”

from

? Besides mice, I mean.”

“Mice?” huffed Horatio. “It’s a bit more serious than

mice

.” The cat looked up at Olive intently. “If you must know, it is something much bigger and much stronger than you are prepared to deal with. Believe me.”

mice

.” The cat looked up at Olive intently. “If you must know, it is something much bigger and much stronger than you are prepared to deal with. Believe me.”

Something about Horatio’s stare made Olive’s skin prickle, but she tried not to let him see.

“Fine,” she said, breaking his gaze and adjusting the spectacles on her nose. “I found an old necklace. That’s all.”

The cat gave a sigh that seemed to rise all the way up from the tip of his tail. “Well, you’re stuck with it now,” he said. “Keep it safe. Don’t let anyone see it.”

“I’ll put it in my jewelry box. It has a lock.”

The cat rolled his green eyes. “No. Once you’ve put it on, you can’t take it off.”

Olive tried. She pulled and pulled on the chain, but she couldn’t seem to lift it over her head. It was as if every time it reached a level with her nose, the pendant suddenly became a magnet—a magnet that was attracted to Olive. The cat watched, with an I-told-you-so expression on his face.

“Keep it under your clothes,” Horatio whispered. “Don’t let her see it.”

“Who?”

“Ms. McMartin!” Horatio hissed, glancing to the left and right anxiously.

“But Ms. McMartin is dead,” said Olive, feeling very slow.

“Of course she’s dead,” said the cat. “But she’s still here. Just keep that necklace safe!”

Olive’s mind clicked back through all the things she had heard and seen. No one would tell her the whole story. All that she had gathered were baffling fragments of something much bigger and much trickier than she had expected. Still, one fragment kept rising to the top. Olive felt a sudden prickle of excitement and fear—the prickle you feel when your shovel hits something hard, quite deep in the ground, before you have any idea what you’ve found. “Horatio,” said Olive, “what do you know about

Aldous

McMartin?”

Aldous

McMartin?”

The cat froze. His ears flattened against his head and his fur stood up like a fluffy Mohawk. Olive glanced around. The violet sky was darkening, like cloth soaking up a spill of black ink. The air seemed to turn colder, heavier. “We’ve been noticed,” Horatio hissed. “We need to get out of here. Quickly.”

In a bound, the cat shot through the frame. Alone in the painting, Olive felt it again: that prickling sensation on the back of her neck, and goose bumps flowing down along her arms. Maybe it was just a cool breeze blowing from across the lake. Or maybe somebody was watching her. What was it that Annabelle had said? That people in this house acted like cats getting startled by their own tails? Well, Olive wasn’t going to get scared so easily. She gave the twilit sky above the lake a last, defiant look. Then she pulled herself through the frame and landed with a flop on the carpeted stairs.

“Olive, dear, you’re soaking,” said Mrs. Dunwoody with mild surprise as she trailed past her down the staircase.

13

B

Y THE TIME Olive changed out of her wet clothes,

Y THE TIME Olive changed out of her wet clothes,

Mr. Dunwoody had dinner ready. Mrs. Dunwoody lit a candle and gave it to Olive to place on the table. Olive helped set their places, poured everyone a glass of water, and even took seconds of the lasagna, but through the whole meal her mind was hopping from clue to clue like a SuperBall.

The paintings. The trapdoor in the basement. The necklace, which hung even now inside her shirt. The attic . . . and the “someone else” who protected it, like Horatio had said. She wasn’t going to stop searching until she found a way into the attic and met that someone. Olive got so excited just thinking about this that she dropped her fork on the floor (three times), and knocked over her water (just once, and luckily the glass was almost empty).

After dinner, Mr. and Mrs. Dunwoody suggested that they all play “Forty-two,” a more complicated version of Twenty-one that Mr. and Mrs. Dunwoody had invented together back in their college days. Olive knew her only escape would be to say she was too tired and wanted to head to bed, but this would have definitely made her parents suspicious. So she stayed. Her feet jittered impatiently under the table.

At first Mr. and Mrs. Dunwoody let Olive win most of the hands, but by 10:30 Olive lost her entire pile of paper clips and fell asleep in her chair, listening to the sounds of her parents whispering romantically about probabilities and numerical combinations.

She woke up in her bed to the song of a robin and a beam of sunlight pouring in through her bedroom window. After shoveling down a heaping bowl of Sugar-Puffy Kitten Bits, Olive scrambled up to the second floor.

This time, she had a new plan. An attic had to have a staircase or a ladder. And if there was a staircase, that meant there had to be a hollow spot within the walls. If she knocked in the right spot, maybe she would hear it.

Olive started in the upstairs hall. At the front of the house, she pressed her ear against the wall and tapped with her knuckles. The wall made a low, solid

thump

. She moved her ear a few inches to the left and tapped again. The wall here sounded the same. Olive made her way slowly around the hallway corner, tapping and listening. She was near the painting of the strange bowl of fruit when she heard something else in the wall. It was muffled, and very distant, but Olive recognized the sound. It was the whine of a dog. Olive held her breath. She slid her ear along the wall. The whining sound grew fainter.

thump

. She moved her ear a few inches to the left and tapped again. The wall here sounded the same. Olive made her way slowly around the hallway corner, tapping and listening. She was near the painting of the strange bowl of fruit when she heard something else in the wall. It was muffled, and very distant, but Olive recognized the sound. It was the whine of a dog. Olive held her breath. She slid her ear along the wall. The whining sound grew fainter.

On the other side of that wall was the pink room. Olive darted inside, catching the usual stale whiff of potpourri and mothballs. She put her ear to the pink wall, a few feet from the huge painting of the ancient town with its giant stone archway. Nothing—no dog whining, no sound at all. She tapped gently. This time, instead of a solid thump, she heard a light, hollow knock. Her heart gave a happy jump. This painting was certainly large enough to hide a door.

Olive yanked on the huge gold frame. It didn’t budge. She wrapped her fingers around its edge and pulled with all her strength. She might as well have been pulling on the wall itself. Olive gave a disappointed huff. Then a new idea floated across her mind.

She put on the spectacles and took a close look at the painting. Nothing changed. The distant trees around the town didn’t shake their leaves. The tufts of grass didn’t move in a soft summer breeze. Cautiously, Olive put out her hand and pushed her fingertips into the painting, right through the center of the giant stone archway, where the two stone soldiers glared down, unchanging. Her hand went easily through, but she couldn’t feel the Mediterranean sun on her skin, or any change in the air. Olive braced herself on one side of the huge frame and pressed her face through the canvas.

At first, all she could see was darkness. She wasn’t in the ruins of a Roman village. She wasn’t in a painting at all. She was looking through it, just like one of those sneaky mirrors that’s actually a window. But there, in the darkness on the other side of the painting, was a thin strip of light. It ran along the bottom edge of an old wooden door. Just above it, a round brass doorknob gave off a reflected glint.

With her heart doing a tap dance against her ribs, Olive stepped through the canvas onto a bare wooden floor, and grasped the handle. The door was heavy. At first it didn’t want to budge, but Olive pulled with both arms, and finally, with a low, vibrating creak, it swung toward her. The scent of dusty air, stale and ancient, swept around Olive like invisible snow.

A wooden staircase angled upward from darkness into faint daylight. Olive shut the door behind her and climbed slowly up the narrow stairs. The steps were littered with the papery bodies of dead wasps and bits of brittle sawdust. Olive hoped that there weren’t any living wasps to worry about—she wasn’t very good with insects.

At the top of the stairs, she stood up, took off the spectacles, and gave the room a long, careful look.

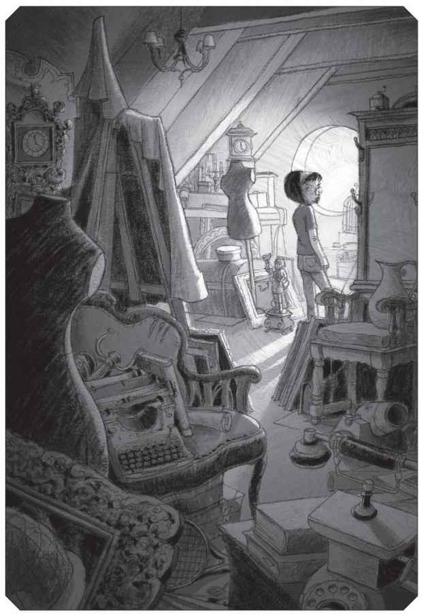

The attic was surprisingly large. Round portal windows cut in each side let in streaks of dusty white sunlight. The ceiling angled sharply up to a point in the middle, with the sides of the room growing lower and lower, so that even a very small person would have had to crouch to reach the corners. But the room itself was not what caught Olive’s attention.

The attic was simply heaped with things. There were sewing mannequins and ancient tapestries, locked steamer trunks and glass-fronted cabinets, upholstered sofas draped with white sheets. There were giant gilt-framed mirrors and dusty dressers. There were the remnants of a Victorian washing machine, a small, battered cannon, and something that looked dauntingly like a dentist’s chair, or, possibly, a torture device.

And, slightly apart from everything else, stood a tall, paint-spattered easel.

Olive edged toward it. A low stool was positioned in front of the easel, and tubes of paint and bottles of powders were ranged along its tray. To the right, a small table held jars full of brushes, more tubes of pigment, and a palette covered with blobs of dried paint. An oilcloth-draped canvas leaned against the easel’s back. Olive reached out, and, with the tips of her fingers, lifted up the cloth and peeped underneath.

The painting on the easel was far from finished. A blue background, which could have been either a wall or the sky, hung behind a wide wooden table that filled the canvas from left to right. On the table lay an open book. And on the book lay a pair of hands. The wrists trailed off into the background, toward a body that had not yet been painted . . . that never

would

be painted, Olive realized.

would

be painted, Olive realized.

Her knees wobbling, she put on the spectacles and looked more closely at the painting. In an instant, the hands came to life, clenching the book. Then they moved hesitantly upward, patting at arms and a face that were not there. Olive jumped away, dropping the cloth back over the canvas. Her stomach fizzed and clenched queasily, as if a huge spider had just run over her skin. This was Aldous McMartin’s studio. This was where he had worked.

Other books

The Fantastic Secret of Owen Jester by O'Connor, Barbara

Learning to Trust: Curtain Falls by B. B. Roman

True To You (Taking Chances #2) by Liwen Ho

Calm, Cool, and Adjusted by Kristin Billerbeck

The Butcher of Anderson Station by James S. A. Corey

The Horse Soldier: Beginnings Series Book 10 by Jacqueline Druga

Silent Girl by Tricia Dower

Shopaholic Ties the Knot by Sophie Kinsella

SG1-15 The Power Behind the Throne by Savile, Steven

Scott Roarke 03 - Executive Command by Gary Grossman