Read The Bletchley Park Codebreakers Online

Authors: Michael Smith

The Bletchley Park Codebreakers (55 page)

To a remarkable degree, the lack of interest in Sigint by historians and specialists in international relations has survived even the revelation of the Ultra secret. Although no historian of the Second World War nowadays fails to make some mention of Ultra, few stop to consider the influence of Sigint on the rest of the twentieth century. Even after the disclosure of Ultra’s role in British and American wartime operations, it took another fifteen years before any historian raised the rather obvious question of whether there was a Russian Ultra on the Eastern Front as well. The great majority of histories of the Cold War do not refer to Sigint at all. Although most studies of US Cold War foreign policy mention the CIA, there is rarely any reference to the NSA – despite the public acknowledgement by George Bush (the first) that Sigint was a ‘prime factor’ in his foreign policy. The small circle of those in the know in Washington used to joke that NSA stood for ‘No Such Agency’. The NSA, however, has a bigger budget than the CIA, employs far more people, and generates far more intelligence.

The abrupt disappearance of Sigint from the historical landscape immediately after VJ Day has produced a series of curious anomalies, even in some of the leading studies of policy-makers and postwar international relations. Thus, for example, Sir Martin Gilbert’s magisterial multi-volume official biography of Churchill acknowledges his passion for Sigint as war leader but fails to discuss his continuing interest in it as peacetime Prime Minister from 1951 to 1955. Similarly, although Eisenhower’s wartime enthusiasm for Ultra is well known, none of his biographers, so far as I am aware, mentions the enormous resources he devoted to Sigint as President of the United States from 1953 to 1961. There is even less about Sigint in biographies of Stalin. Indeed, it is difficult to think of any history of the Soviet Union which devotes as much as a sentence to the enormous volume of Sigint generated by the KGB and GRU. The US embassy in Moscow, however, appears to have been successfully bugged during

the Second World War and for almost twenty years afterwards, and for a significant part of the Cold War, thanks to the achievements of Soviet cryptanalysts, France, Italy and some other NATO countries seem, without realizing it, to have been conducting open diplomacy in their dealings with the Soviet Union.

Although the neglect of Sigint by many leading historians is due partly to the overclassification of intelligence archives, it derives at root from what educational psychologists call ‘cognitive dissonance’ – the difficulty all of us have in grasping new concepts which disturb our existing view of the world. For many twentieth-century historians, political scientists and international relations specialists, secret intelligence was just such a concept. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, however, the traditional academic disregard for intelligence is in serious, if not yet terminal, decline. A new generation of scholars has begun to emerge, less disoriented than their predecessors by the role of intelligence and its use (or abuse) by policy-makers. A vast research agenda awaits them.

In the meantime, the story of Bletchley Park and what has begun to emerge about the history of cryptanalysis in the remainder of the twentieth century confronts all historians of the Cold War and international relations specialists with a major challenge, which most have avoided so far: either to seek to take account of the role of Sigint since the Second World War or to explain why they do not consider it necessary to do so.

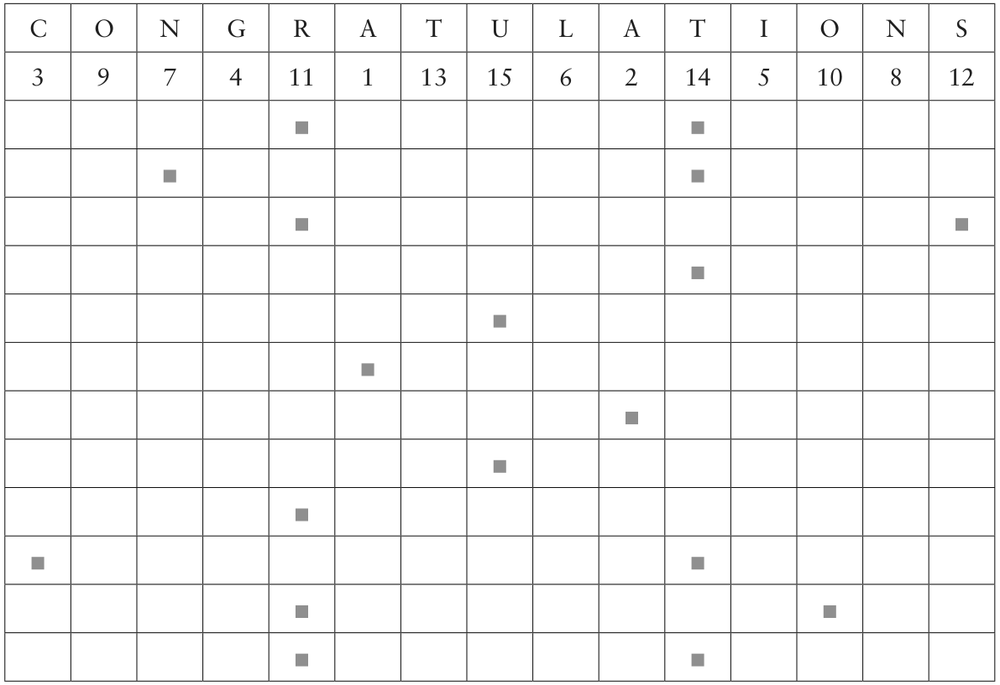

THE VERY SIMPLE CIPHER WHICH ‘SNOW’, THE FIRST DOUBLE CROSS AGENT, WAS GIVEN BY HIS GERMAN CONTROLLERS

The code is based on the word CONGRATULATIONS, and the grid is set out as follows:

KEY blank space

blank space

1st blank = 5

2nd blank = 5 + 6 = 11

3rd blank = 11 + 7 = 18

4th blank = 18 + 8 = 26

5th blank = 26 + 9 = 35

6th blank = 35 + 10 = 45

7th blank = 45 + 11 = 56

8th blank = 56 + 12 = 68

9th blank = 68 + 13 = 81

The grid is 15 squares long (to fit the 15 letters of CONGRATULATIONS) and 12 squares deep, this last figure being chosen for convenience.

The blank spaces are decided as follows:

The first blank space is placed, quite arbitrarily, at the 5th space, reading from left to right and starting at the left-hand top corner.

The next is 6 spaces after, i.e. at the 11th space, the next is 7 spaces after that, i.e. at the 18th space, and so on in arithmetical progression until the 9th blank, placed at the 81st space, is reached. It will be found that this is in the row of the grid, i.e. halfway down.

The grid is now turned upside down and the same procedure followed as above, so that the blanks are symmetrical.

The message to be coded is now written in the grid, ignoring the blanks, that is to say, no letter must be written in a blank space. The blanks are then filled in with any letter which can be chosen quite arbitrarily.

At the top of the grid, the word CONGRATULATIONS is filled in, and underneath this each letter is numbered in order of the alphabet. Thus, A is 1, the second A is 2, C is 3, G is 4, and so on, until each column of the grid is numbered.

The procedure for sending out the message is as follows:

A line should be drawn at the end of the message when written out in the grid to separate it from the unused portion of the grid.

Each column (downwards) of letters is then written out, the order depending on the date on which the message is being sent. Thus if the date is the 8th of the month, the column headed 8 is written out, followed by the column headed 9, then 10 and so on until the string of letters is ended with the column headed 7. Should the date be more than 15, e.g. the 20th of the month, subtract 15 from the date

and start on the difference, i.e. 5. This long string of letters is then counted off into blocks of 5 letters each, and in this form the message is transmitted.

Before the actual message is sent, the time, date and number of letters in the message is given. These are coded as follows:

The word CONGRATULATIONS is written out and those letters which recur, i.e. A, T, O and N are struck out, and the remaining letters numbered thus:

I and S are numbered 0 (nought) and can be used indiscriminately to represent this number.

The time of transmitting is then coded on this scale. E.g. if the time is 10.30 p.m., i.e. 2230 hours, this would be coded as OONI (or OONS); or 1245 hours would be coded as COGR.

The date on which the transmission is taking place is similarly coded, the day and month only being sent.

The total number of letters (i.e. including the ‘bogus’ letters used to fill in the blanks) is then sent using the same code.

N.B. If the message being transmitted is in answer to a message just received, and the time and date are therefore very much the same, it is possible that they may be omitted.

(Reproduced with thanks to the Public Record Office. PRO KV 2/453)

WEHRMACHT ENIGMA INDICATING SYSTEMS, EXCEPT THE

KRIEGSMARINE’S KENNGRUPPENBUCH

SYSTEM

Heer and Luftwaffe

indicating system from 1 May 1940 onwards (except on Yellow): singly enciphered message keys.

To encipher a message, the operator first set up his machine according to the daily key (rotor order,

Stecker

and ring settings). He then –

a) chose a random group of three letters for the

Grundstellung

(the setting of the rotors when starting to encipher or decipher the message key) (e.g. WEP), wrote it down, and set his rotors to those positions;

b) chose three letters (e.g. RNL) as a message key, and typed them once only (RNL), producing perhaps HFI, which he again wrote down;

c) turned the rotors to RNL, and entered the plain-text of the message, writing down each letter as it lit up on the lampboard (generally a two-man operation, with one man writing as the other typed the text).

The transmitted message included –

d) the sender’s and receiver’s call signs;

e) a five-letter group consisting of two null letters (which were dropped later), followed by a three-letter discriminant, which showed which Enigma cipher was being employed. This allowed the recipient to look up and use the correct key-list (e.g. that for Red);

f) the unenciphered

Grundstellung

, followed by the three letters of the enciphered message key;

g) the enciphered text, in five-letter groups.

A typical

Heer

or

Luftwaffe

Enigma message is shown in Figure AII.1, with its various components marked. To decipher the text, the receiving operator set up his machine according to the daily key (rotor order,

Stecker

and ring settings).

He then –

h) set his rotors to the

Grundstellung

(WEP);

i) typed HFI – which lit up the lamps for RNL;

j) turned his rotors to RNL, and entered the cipher text, writing down the resulting letters as they lit up (again, often a two-man operation).

Heer and Luftwaffe

indicating system from 15 September 1938 to 30 April 1940: doubly enciphered message keys.

The system was the same as that above, except that the operator typed the message key twice (say RNLRNL), producing perhaps HFIKLB. The group following the

Grundstellung

therefore consisted of six letters.

Figure AII.1

Heer

or

Luftwaffe

signal, as intercepted in September 1942

The following is a typical

Heer

or

Luftwaffe

Enigma signal, as intercepted by a US Army station in September 1942:

9UL

1

DE

2

C

3

6350 KCS

4

S 2/3

5

R 2/3

6

U S 20

7

KA

8

2005

9

BT

10

KR

11

BT

10

2TLE

12

BT

10

1 TLE

13

249

14

BT

10

YHX

15

LVI

16

WHX

17

BT

10

MBXSS … EYEMW

18

AR

19

13SE

20

2023Z

21

HH

22

1. Station being called

2. From

3. Station calling (C = control)

4. Frequency

5. Signal strength (between 2 & 3)

6. Readability (between 2 & 3)

7. Intercept station no.

8. Beginning of preamble

9. German time of origin

10. Separator

11. Urgency signal (not always present)

12. Total number of parts in the signal

13. No. of this part (

Teile

) of the signal

14. No. of letters in this part

15. Cipher discriminant

16. Grundstellung

17. Enciphered message key

18. Cipher text

19. Message

Teil

complete

20. Date of intercept – 13 September 1942

21. Time of intercept

22. Operator’s identification

Heer and Luftwaffe

indicating system before 15 September 1938.

This system was the same as that in force from 15 September 1938 to 30 April 1940, except that the

Grundstellung

was set out in a key-list as part of the daily key, and not chosen by the operator:

‘Throw-on’ (‘boxing’) naval Enigma indicator system used before 1 May 1937, and for six wartime ciphers.

The naval indicating system employed before 1 May 1937 (called a ‘throw-on’ system by GC&CS) was the same as the

Heer

and

Luftwaffe

indicating system before 15 September 1938, with the

Grundstellung

being set out in a key-list, as part of the daily key. The message key may have been chosen from a list of 1,700 trigrams, and not left to the operator’s discretion, but that is not clear. No

Kenngruppenbuch

or bigram tables were used. It is not known whether a cipher discriminant was incorporated then: only one cipher may have been in operation. The combination of doubly enciphered message keys and a single daily

Grundstellung

made it an appallingly weak system (see Chapter 11). The

Kriegsmarine

changed to the much more secure

Kenngruppenbuch

system (see Appendix III) on 1 May 1937.

However, in a series of catastrophic blunders, the

Kriegsmarine

employed the pre-1 May 1937 system for six naval wartime ciphers: Porpoise, Seahorse, Sunfish, Trumpeter, Bonito and Grampus, enabling Hut 8 and OP-20-G to penetrate them. Operators were permitted to choose their own message keys for these ciphers, subject to some very simple rules (e.g. words, and alphabetical sequences, such as HIJ, were banned): there was no list to choose from. This greatly assisted Hut 8 in breaking what was already a very weak system, which the

Heer

and

Luftwaffe

had discarded on the grounds of its insecurity in September 1938 (dropping of the daily

Grund

) and 1 May 1940 (abandonment of doubly enciphered message keys).