The Big Ratchet: How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis (15 page)

Read The Big Ratchet: How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis Online

Authors: Ruth DeFries

Less salubrious cargo also found new homes. Sailors unknowingly brought smallpox, tuberculosis, measles, whooping cough, bubonic plague, typhus, and malaria westward from the Old World. Diseases decimated New World populations who had no resistance to the crowd diseases that settled life amid livestock had conferred on the people of the Old World. So many died that more people might have perished in the Americas from the Old World diseases than in Europe during the Black Death. Syphilis may have gone in the other direction, from the New World to the Old, though

scholars do not agree on this point.

The English interpreted the decimation wrought by Old World diseases as divine providence. King James’s 1620 charter granted “the planting, ruling, ordering, and governing of

New England in America” to the Plymouth Company, claiming that “God’s visitation reigned a wonderfull Plague . . . so that there is not left . . . any that doe claime or challenge any

Kind of Interests therein.” The charter proceeded to justify the takeover of the landscapes left empty from the ravages of disease: “We in our Judgment are persuaded and satisfied that the appointed Time is come in which Almighty God in his great Goodness and Bountie towards Us and our People, hath thought fitt and determined, that those large and goodly Territoryes, deserted as it were by their naturall Inhabitants, should be possessed and enjoyed by such of our Subjects and People.” A decade and a half later, John Winthrop,

a leading figure in the New England settlement at Plymouth, wrote a letter back home reporting on the progress for feeding the Plymouth settlers from “all sorts of roots, pumpkins and other fruits for which taste and wholesomeness far exceed those in England: our grapes also afford a good hard wine.” Winthrop proceeded to discuss the weather, taxes, and other facets of daily life. He concluded, “For the natives, they are near all dead of smallpox, so the Lord hath cleared our

title to what we possess.”

Europe’s entry into the New World transformed people’s diets across every continent. Chinese meals were now enriched with New World corn, peanuts, sweet potatoes, and white potatoes, high in nutrition and

easy to grow in poor soil. New World crops of corn and manioc spread to Africa, where they became the staple for millions,

completely transforming the diet. White and sweet potatoes and corn brought nutritionally rich staples from the New World to Europe to supplement wheat, barley, and rye.

Luxury commodities from across the oceans brought variety to the European diet. Coffee and sugar, Old World crops that developed into New World commodities, became inexpensive enough to be enjoyed by common Europeans. With tea arriving in Europe from China in the early seventeenth century, as well as chocolate, which Columbus brought back to Europe on his third voyage to the New World, hot sweetened drinks became part of the culture. By the late eighteenth century, a French observer of English customs noted that “the humblest peasant has high tea twice a day just like the rich man; the

total consumption is immense.” Each person in England, on average, was consuming about two pounds of sugar each year by the mid-seventeenth century. That number shot up to

twenty-three pounds within a century. People could enjoy the taste of fruits year round in the jams and marmalades made with sugar. By the early eighteenth century, breakfast was less often porridge and cold cuts with wine or beer than it was bread, jam, and sweetened coffee or tea.

Old World crops and animals flourished in their new American home. Sheep, horses, cattle, and pigs had abundant space to graze and few predators. A royal official wrote to Spain’s king in 1518 about the “marvelous multiplications of livestock,” requesting that boats setting sail from Spain bring more

animals to the New World. Horses could pull plows and haul loads to subsidize human labor in the New World. The ultimate expansion of wheat, corn, and soy across the North American plains a few centuries later, a story we return to in a later chapter, would not have been possible without the subsidized labor from horses.

Old World crops grew well in the New World because there were few pests to hinder them and vast expanses of land that had been left even emptier from the decimation of native peoples. Sugarcane, first domesticated in Asia and brought to Europe by the Arabs in the tenth century, stood to become a particularly lucrative crop, and European demand for sugar soared. But human labor to produce the commodity was in short supply in the tropical Americas, and native populations succumbed too readily to disease to be a reliable source for coerced labor. Africans had built up more resistance to Old World diseases. The trade winds that had brought Columbus also carried roughly 12 million Africans to the New World during the transatlantic

slave trade between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. The energy subsidy from coerced human labor, at a cost of feeding, transporting, and purchasing the slaves, earned sugar growers heavy profits during this dark time in human history.

The brief period of the Age of Discovery, powered by sails harnessing the sun’s energy in the form of wind, ranks as one of the most pivotal eras of all in the history of humanity’s twists of nature. Diets, energy sources, and cultures transformed around the world. Imagine Italian cuisine without tomatoes, Indian dishes without chilies, or West Africans without fufu pounded from cassava. Think of European settlers in North

America without horse-drawn covered wagons, or France without coffee served in cafés.

The biological homogenization upended the entire natural world as well. Carolus Culsius, the doctor and botanist famous for making the tulip industry possible in Holland, found particular fascination in the plants and animals that explorers brought to Europe from every corner of the world. Although he never set foot out of Europe, he received thousands of letters from his network of travelers. And they came with descriptions, pictures, seeds, nuts, bulbs, tubers, and live plants. His 1605 illustrated compendium

Exoticorum Libri Decem

(Ten Books of Exotica) covered the history and uses of animals, plants, aromatics, and other natural products from distant lands. It included the armadillo from South America, birds of paradise from the East Indies, and the

flying dragon from Southeast Asia. Although his volumes contain hundreds of plants and animals, these are probably only a fraction of the massive shifts in the biological world brought by trade and exploration from the sun-powered wind.

Trade changed what people ate and how they farmed. Europe benefited from the new calorie-rich staple crops. The New World got horses and other animals to supplement human labor. The horrible downside to the exchange was the rise of slavery that powered the transport of sugar, coffee, tobacco, and then cotton to the Old World, which disrupted African cultures on a massive scale. The decimation of native cultures in the Americas was another cost beyond counting. The great swap had enormous costs for humanity through the decimation of these cultures. It also amplified humanity’s ability to feed itself from the coerced energy, locking civilization into feeding more and more people.

Sun-powered sails made possible yet another boost to what people could eat, this time in the form of water disguised in fruits, vegetables,

and grains. Since the times of ships to ply cargo and overland caravans pulled by camels and horses, trade across the continents has helped societies out of their ecological dilemmas. In places where water is scarce, for instance, trade brought products to people—apples, avocados, corn, meat, and so on—that required many pounds of water to grow or raise. The products are, essentially, water traveling in disguise. Thus, the vast amounts of water that a crop can consume—about 1,000 pounds of water, even 5,000 where temperatures are high, for every pound of grain—are

surreptitiously part of the trade.

This “virtual” water embedded in a product and transported through trade redistributes water

from one place to another. Instead of the impractical prospect of shipping huge quantities of water, one need only ship the product produced from the water. This by-product of trade is even older than the Silk Road, with merchants in caravans bearing juicy oranges, grapes, and pomegranates from very early times.

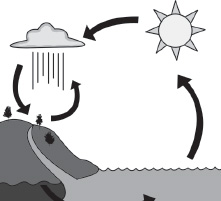

Nothing is more vital to humanity’s ability to feed itself than a secure supply of water. Even before modern science unraveled the continual path of water from oceans to atmosphere to land and back to the oceans, scholars suspected that the cycling of water was one of the marvels of the planet. Ancient Chinese texts speak of circular motion in terms of the water cycle: “Cloud turns into rain while moving west, falls

to the ground, and then flows from west to east along the terrain into the sea, [and] the sea water

again evaporates into the cloud.” The Greek philosopher Xenophanes also noted the concept of cycling in the fifth century

BCE

, writing that “The sea is the source of the water, and the source of the winds. Without the great sea, not from clouds could come the flowing rivers or the heaven’s rain; but the great sea is the father of clouds,

of rivers and of winds.”

Today, schoolchildren learn the basics of the planetary machinery that keeps water continuously moving and changing forms from liquid to solid ice to water vapor and back. In the words of geologist John Hutton, there is no beginning and no end, but the sun is as good a place start as any. The sun evaporates water from the surface of the ocean. The moisture travels long distances in the form of clouds, then rains or snows on the land or the oceans. The water can either evaporate, returning back to the atmosphere; flow as runoff into streams and other bodies of water; or seep through the surface of the Earth to become groundwater. Groundwater flows through the soil and trickles through rock back into streams and rivers, which eventually flow into the ocean. Back in the ocean, the process begins anew. The journey takes anywhere from days, for a water molecule cycling from the surface to become rain

and then fall back to the ground, to tens of thousands of years, for water locked underground, in ice, or in deep oceans.

Plants play a role as well, pulling water from the soil and transpiring it to the atmosphere. If water vapor were visible, a plant would look like a fountain spewing water into the air. For wheat, corn, rice, tomatoes, or any other plant that people eat, this is the step in the planetary machinery that is so critical. The soil water carries dissolved nutrients to a plant’s roots and keeps the plant from wilting.

Since the dawn of agriculture, the challenge for human ingenuity has been how to get water to the plants that we eat. The paltry percentage of the entire planet’s water that is not too salty or not locked up in ice

is not really the issue. There is plenty, save for two problems. One lies in timing. Take, for example, a place like the Indian subcontinent, with its torrential monsoon rains. There is plenty of rain; it just all falls within a few months and leaves the fields parched for the remainder. Dams, a solution to the timing problem, go back to antiquity; they return later in our story as we march forward to more contemporary times.

Another solution is to pull up the great stores of water beneath the ground. Before wells, people could only live in places near naturally occurring springs, such as ancient Jericho, or along streams and rivers. People had the idea to dig wells at least as far back as the time when agriculture began. They dug to reach the water table as best they could by hand and with shovels, but they could only reach water tables fairly near the surface. The Chinese leap in technology around 4,000 years ago, repeated drumming of a bit against hard rock, could reach deep stores of

water thousands of feet below the ground.

The

qanat

, invented by the Persians in the first millennium

BCE

, represented another ancient, ingenious advance in carrying groundwater. The qanat brought water from mountain highlands to arid plains long before pumps could do the job. In this system, a vertical mother-well penetrated the water table in the uplands, and a gently sloping horizontal

underground conduit carried the water above the water table under the force of gravity. At the outlet, a network of channels distributed the water to fields and towns. The qanat ensured a continuous supply of water. The marvel spread throughout arid regions from Pakistan to Egypt, and later as far as China and Spain, under different names, including

keriz

in a local language of China, and

foggara

and

khettera

in languages of the Sahara Desert. Some of the oldest and largest qanats still exist, such as one in the Iranian city of Gonabad that still provides irrigation and drinking water to

nearly 40,000 people.