The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (50 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

BOOK: The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History

8.45Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

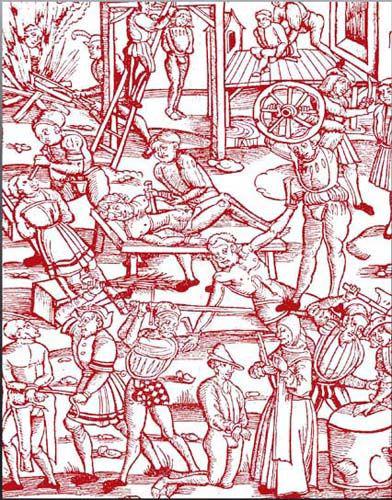

After hanging, ‘breaking with the wheel’ was the most common means of execution throughout Germanic Europe from the early Middle Ages to the beginning of the eighteenth century. The victim, naked, was stretched out supine on the ground with his or her limbs spread and tied. Crosspieces were placed under the wrists, elbows, ankles, knees and hips. The executioner then smashed limb after limb and joint after joint, including the shoulders and the hips, using the iron edged wheel, being careful to avoid fatal blows. The victim was transformed, according to the observations of a seventeenth-century chronicler, ‘into a sort of huge screaming puppet with four tentacles, like a sea monster, of raw, slimy and shapeless flesh mixed up with splinters of smashed bones’. Then the shattered limbs were ‘braided’ into the spokes of the wheel, and the victim hoisted up horizontally to the top of a pole, where they were left for the birds and exposure to the elements to slowly perish. Death came after a long and atrocious agony. This method of execution seems to have been a popular spectacle in medieval Europe.

Although forever associated in the cultural imagination with the French Revolution, devices which mechanically decapitate by means of a falling blade existed long before the birth of Dr Joseph Guillotin. Primitive ancestors of the guillotine were used in Ireland, England and Italy in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Several known decapitation devices, such as the Italian Mannaia, the Scottish Maiden and the Halifax Gibbet are well documented and pre-date the use of the French guillotine by as much as 500 years.

At the bottom of the page is an image depicting one of these early ancestors of the guillotine, known as a Fallbrett (literally, a ‘falling board’). In this instance, there is no sharpened (or even metal) blade to sever the head from the body in one swift stroke, but rather this device is simply constructed of planks of solid oak. Here it is the blunt edge of the wood alone which rips and chews the flesh and vertebrae under the impact of the sledge blows. Presumably by breaking the neck on the first blow the victim would be spared a prolonged and tortuous death, though that would be rather uncertain. It is of course possible that a broken neck may simply result in paralysis rather than death, and so the victim would have to suffer through the entire ordeal as the executioner wielded sledge blow after sledge blow.

When one thinks of torture by stretching, this device – known by many names, but most commonly referred to as the rack – springs immediately to mind.

When ‘racked’ the victim is literally ‘prolonged’ by force of the winch, and various sources testify to cases of thirty ems or twelve inches! This inconceivable length comes of the dislocation and extrusion of every joint in the arms and legs, of the dismemberment of the spinal column, and of course of the ripping and detachment of the muscles of the limbs, thorax and abdomen – effects that are, needless to say, somewhat fatal.

But long before the victim is brought to the final undoing, he or she, often in the ‘Question of the first degree’ suffers dislocation of the shoulders because his arms are pulled up behind his back, as well as the agony of muscles ripping like any fibre subjected to excessive stress. In the ‘Question of the second degree’, the knee, hip and elbow joints begin to be forced out of their sockets; with the ‘third degree’ they separate, very audibly. After only the second degree, the victim is maimed for life; after the third he is dismembered and paralysed and gradually, over hours and days, the life functions cease one by one.

This example has spiked rollers, which is a refinement that is more of an exception than a rule.

Other books

Blog of the Dead (Book 1): Sophie by Richardson, Lisa

The Contaxis Baby by Lynne Graham

The Demon's Brood by Desmond Seward

Identity Thief by JP Bloch

Heart of the Kraken (Tales from Darjee) by Exley, A. W.

Novel - Airman by Eoin Colfer

Countdown by Natalie Standiford

Tenacious Trents 01 - A Misguided Lord by Jane Charles

Suspect Zero by Richard Kadrey

Yarrow by Charles DeLint