The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (50 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Amazon.com, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Social History, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

6.19Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

I already mentioned some evidence from Richardson’s dataset which suggests that combatants do fight longer when a war is more lethal: small wars show a higher probability of coming to an end with each succeeding year than do large wars.

66

The magnitude numbers in the Correlates of War Dataset also show signs of escalating commitment: wars that are longer in duration are not just costlier in fatalities; they are costlier than one would expect from their durations alone.

67

If we pop back from the statistics of war to the conduct of actual wars, we can see the mechanism at work. Many of the bloodiest wars in history owe their destructiveness to leaders on one or both sides pursuing a blatantly irrational loss-aversion strategy. Hitler fought the last months of World War II with a maniacal fury well past the point when defeat was all but certain, as did Japan. Lyndon Johnson’s repeated escalations of the Vietnam War inspired a protest song that has served as a summary of people’s understanding of that destructive war: “We were waist-deep in the Big Muddy; The big fool said to push on.”

66

The magnitude numbers in the Correlates of War Dataset also show signs of escalating commitment: wars that are longer in duration are not just costlier in fatalities; they are costlier than one would expect from their durations alone.

67

If we pop back from the statistics of war to the conduct of actual wars, we can see the mechanism at work. Many of the bloodiest wars in history owe their destructiveness to leaders on one or both sides pursuing a blatantly irrational loss-aversion strategy. Hitler fought the last months of World War II with a maniacal fury well past the point when defeat was all but certain, as did Japan. Lyndon Johnson’s repeated escalations of the Vietnam War inspired a protest song that has served as a summary of people’s understanding of that destructive war: “We were waist-deep in the Big Muddy; The big fool said to push on.”

The systems biologist Jean-Baptiste Michel has pointed out to me how escalating commitments in a war of attrition could produce a power-law distribution. All we need to assume is that leaders keep escalating as a constant proportion of their past commitment—the size of each surge is, say, 10 percent of the number of soldiers that have fought so far. A constant proportional increase would be consistent with the well-known discovery in psychology called Weber’s Law: for an increase in intensity to be noticeable, it must be a constant proportion of the existing intensity. (If a room is illuminated by ten lightbulbs, you’ll notice a brightening when an eleventh is switched on, but if it is illuminated by a hundred lightbulbs, you won’t notice the hundred and first; someone would have to switch on another

ten

bulbs before you noticed the brightening.) Richardson observed that people perceive lost lives in the same way: “Contrast for example the many days of newspaper-sympathy over the loss of the British submarine

Thetis

in time of peace with the terse announcement of similar losses during the war. This contrast may be regarded as an example of the Weber-Fechner doctrine that an increment is judged relative to the previous amount.”

68

The psychologist Paul Slovic has recently reviewed several experiments that support this observation.

69

The quotation falsely attributed to Stalin, “One death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic,” gets the numbers wrong but captures a real fact about human psychology.

ten

bulbs before you noticed the brightening.) Richardson observed that people perceive lost lives in the same way: “Contrast for example the many days of newspaper-sympathy over the loss of the British submarine

Thetis

in time of peace with the terse announcement of similar losses during the war. This contrast may be regarded as an example of the Weber-Fechner doctrine that an increment is judged relative to the previous amount.”

68

The psychologist Paul Slovic has recently reviewed several experiments that support this observation.

69

The quotation falsely attributed to Stalin, “One death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic,” gets the numbers wrong but captures a real fact about human psychology.

If escalations are proportional to past commitments (and a constant proportion of soldiers sent to the battlefield are killed in battle), then losses will increase exponentially as a war drags on, like compound interest. And if wars are attrition games, their durations will also be distributed exponentially. Recall the mathematical law that a variable will fall into a power-law distribution if it is an exponential function of a second variable that is distributed exponentially.

70

My own guess is that the combination of escalation and attrition is the best explanation for the power-law distribution of war magnitudes.

70

My own guess is that the combination of escalation and attrition is the best explanation for the power-law distribution of war magnitudes.

Though we may not know exactly why wars fall into a power-law distribution, the nature of that distribution—scale-free, thick-tailed—suggests that it involves a set of underlying processes in which size doesn’t matter. Armed coalitions can always get a bit larger, wars can always last a bit longer, and losses can always get a bit heavier, with the same likelihood regardless of how large, long, or heavy they were to start with.

The next obvious question about the statistics of deadly quarrels is: What destroys more lives, the large number of small wars or the few big ones? A power-law distribution itself doesn’t give the answer. One can imagine a dataset in which the aggregate damage from the wars of each size adds up to the same number of deaths: one war with ten million deaths, ten wars with a million deaths, a hundred wars with a hundred thousand deaths, all the way down to ten million murders with one death apiece. But in fact, distributions with exponents greater than one (which is what we get for wars) will have the numbers skewed toward the tail. A power-law distribution with an exponent in this range is sometimes said to follow the 80:20 rule, also known as the Pareto Principle, in which, say, the richest 20 percent of the population controls 80 percent of the wealth. The ratio may not be 80:20 exactly, but many power-law distributions have this kind of lopsidedness. For example, the 20 percent most popular Web sites get around two-thirds of the hits.

71

71

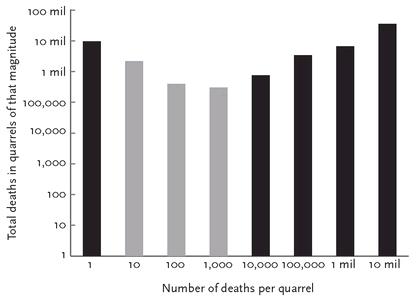

Richardson added up the total number of deaths from all the deadly quarrels in each magnitude range. The computer scientist Brian Hayes has plotted them in the histogram in figure 5–11. The gray bars, which tally the deaths from the elusive small quarrels (between 3 and 3,162 deaths), don’t represent actual data, because they fall in the criminology-history crack and were not available in the sources Richardson consulted. Instead, they show hypothetical numbers that Richardson interpolated with a smooth curve between the murders and the smaller wars.

72

With or without them, the shape of the graph is striking: it has peaks at each end and a sag in the middle. That tells us that the most damaging kinds of lethal violence (at least from 1820 to 1952) were murders and world wars; all the other kinds of quarrels killed far fewer people. That has remained true in the sixty years since. In the United States, 37,000 military personnel died in the Korean War, and 58,000 died in Vietnam; no other war came close. Yet an average of 17,000 people are murdered in the country

every year

, adding up to almost a million deaths since 1950.

73

Likewise, in the world as a whole, homicides outnumber war-related deaths, even if one includes the indirect deaths from hunger and disease.

74

72

With or without them, the shape of the graph is striking: it has peaks at each end and a sag in the middle. That tells us that the most damaging kinds of lethal violence (at least from 1820 to 1952) were murders and world wars; all the other kinds of quarrels killed far fewer people. That has remained true in the sixty years since. In the United States, 37,000 military personnel died in the Korean War, and 58,000 died in Vietnam; no other war came close. Yet an average of 17,000 people are murdered in the country

every year

, adding up to almost a million deaths since 1950.

73

Likewise, in the world as a whole, homicides outnumber war-related deaths, even if one includes the indirect deaths from hunger and disease.

74

FIGURE 5–11.

Total deaths from quarrels of different magnitudes

Total deaths from quarrels of different magnitudes

Source:

Graph from Hayes, 2002, based on data in Richardson, 1960.

Graph from Hayes, 2002, based on data in Richardson, 1960.

Richardson also estimated the proportion of deaths that were caused by deadly quarrels of all magnitudes combined, from murders to world wars. The answer was 1.6 percent. He notes: “This is less than one might have guessed from the large amount of attention which quarrels attract. Those who enjoy wars can excuse their taste by saying that wars after all are much less deadly than disease.”

75

Again, this continues to be true by a large margin.

76

75

Again, this continues to be true by a large margin.

76

That the two world wars killed 77 percent of the people who died in all the wars that took place in a 130-year period is an extraordinary discovery. Wars don’t even follow the 80:20 rule that we are accustomed to seeing in power-law distributions. They follow an 80:2 rule: almost 80 percent of the deaths were caused by

2 percent

of the wars.

77

The lopsided ratio tells us that the global effort to prevent deaths in war should give the highest priority to preventing the largest wars.

2 percent

of the wars.

77

The lopsided ratio tells us that the global effort to prevent deaths in war should give the highest priority to preventing the largest wars.

The ratio also underscores the difficulty of reconciling our desire for a coherent historical narrative with the statistics of deadly quarrels. In making sense of the 20th century, our desire for a good story arc is amplified by two statistical illusions. One is the tendency to see meaningful clusters in randomly spaced events. Another is the bell-curve mindset that makes extreme values seem astronomically unlikely, so when we come across an extreme event, we reason there must have been extraordinary design behind it. That mindset makes it difficult to accept that the worst two events in recent history, though unlikely, were not astronomically unlikely. Even if the odds had been increased by the tensions of the times, the wars did not have to start. And once they did, they had a constant chance of escalating to greater deadliness, no matter how deadly they already were. The two world wars were, in a sense, horrifically unlucky samples from a statistical distribution that stretches across a vast range of destruction.

THE TRAJECTORY OF GREAT POWER WARRichardson reached two broad conclusions about the statistics of war: their timing is random, and their magnitudes are distributed according to a power law. But he was unable to say much about how the two key parameters—the probability of wars, and the amount of damage they cause—change over time. His suggestion that wars were becoming less frequent but more lethal was restricted to the interval between 1820 and 1950 and limited by the spotty list of wars in his dataset. How much more do we know about the long-term trajectory of war today?

There is no good dataset for all wars throughout the world since the start of recorded history, and we wouldn’t know how to interpret it if there were. Societies have undergone such radical and uneven changes over the centuries that a single death toll for the entire world would sum over too many different kinds of societies. But the political scientist Jack Levy has assembled a dataset that gives us a clear view of the trajectory of war in a particularly important slice of space and time.

The time span is the era that began in the late 1400s, when gunpowder, ocean navigation, and the printing press are said to have inaugurated the modern age (using one of the many definitions of the word

modern

). That is also the time at which sovereign states began to emerge from the medieval quilt of baronies and duchies.

modern

). That is also the time at which sovereign states began to emerge from the medieval quilt of baronies and duchies.

The countries that Levy focused on are the ones that belong to the

great power system

—the handful of states in a given epoch that can throw their weight around the world. Levy found that at any time a small number of eighthundred-pound gorillas are responsible for a majority of the mayhem.

78

The great powers participated in about 70 percent of all the wars that Wright included in his half-millennium database for the entire world, and four of them have the dubious honor of having participated in at least a fifth of all European wars.

79

(This remains true today: France, the U.K., the United States, and the USSR/Russia have been involved in more international conflicts since World War II than any other countries.)

80

Countries that slip in or out of the great power league fight far more wars when they are in than when they are out. One more advantage of focusing on great powers is that with footprints that large, it’s unlikely that any war they fought would have been missed by the scribblers of the day.

great power system

—the handful of states in a given epoch that can throw their weight around the world. Levy found that at any time a small number of eighthundred-pound gorillas are responsible for a majority of the mayhem.

78

The great powers participated in about 70 percent of all the wars that Wright included in his half-millennium database for the entire world, and four of them have the dubious honor of having participated in at least a fifth of all European wars.

79

(This remains true today: France, the U.K., the United States, and the USSR/Russia have been involved in more international conflicts since World War II than any other countries.)

80

Countries that slip in or out of the great power league fight far more wars when they are in than when they are out. One more advantage of focusing on great powers is that with footprints that large, it’s unlikely that any war they fought would have been missed by the scribblers of the day.

As we might predict from the lopsided power-law distribution of war magnitudes, the wars among great powers (especially the wars that embroiled several great powers at a time) account for a substantial proportion of all recorded war deaths.

81

According to the African proverb (like most African proverbs, attributed to many different tribes), when elephants fight, it is the grass that suffers. And these elephants have a habit of getting into fights with one another because they are not leashed by some larger suzerain but constantly eye each other in a state of nervous Hobbesian anarchy.

81

According to the African proverb (like most African proverbs, attributed to many different tribes), when elephants fight, it is the grass that suffers. And these elephants have a habit of getting into fights with one another because they are not leashed by some larger suzerain but constantly eye each other in a state of nervous Hobbesian anarchy.

Levy set out technical criteria for being a great power and listed the countries that met them between 1495 and 1975. Most of them are large European states: France and England/Great Britain/U.K. for the entire period; the entities ruled by the Habsburg dynasty through 1918; Spain until 1808; the Netherlands and Sweden in the 17th and early 18th centuries; Russia/USSR from 1721 on; Prussia/ Germany from 1740 on; and Italy from 1861 to 1943. But the system also includes a few powers outside Europe: the Ottoman Empire until 1699; the United States from 1898 on; Japan from 1905 to 1945; and China from 1949. Levy assembled a dataset of wars that had at least a thousand battle deaths a year (a conventional cutoff for a “war” in many datasets, such as the Correlates of War Project), that had a great power on at least one side, and that had a state on the other side. He excluded colonial wars and civil wars unless a great power was butting into a civil war on the side of the insurgency, which would mean that the war had pitted a great power against a foreign government. Using the Correlates of War Dataset, and in consultation with Levy, I have extended his data through the quarter-century ending in 2000.

82

82

Other books

Badwater by Clinton McKinzie

After the Internship: A Novella (The Intern #4) by Brooke Cumberland

Checkered Crime: A Laurel London Mystery by Kappes, Tonya

Storms by Carol Ann Harris

Pride of the Courtneys by Margaret Dickinson

La gran caza del tiburón by Hunter S. Thompson

Moon Thrall by Donna Grant

Forever Santa by Leeanna Morgan

The Squirting Donuts by David A. Adler

Scales of Gold by Dorothy Dunnett