The Battle of Poitiers 1356 (17 page)

Read The Battle of Poitiers 1356 Online

Authors: David Green

An English or French knight did not fight alone, he was part of a small group who served his needs and protected him. Usually this took the following form:

English: (described as a lance), comprising a knight, man-at-arms and two mounted archers (fought on foot)

French: man-at-arms, an esquire, three mounted archers and a hobelar (light cavalryman)

Armour: Mixture of chain-mail, cuir-bouilli (hardened leather), and half-plate.

Armour was undergoing a considerable evolution in this period. The wargamer may wish to arm the more experienced and affluent troops with the more ‘modern’ styles.

An aketon or simplified hauberk provided padding and a securing place for metal plates and areas of chain mail which protected the articulated parts and extended beyond the lower edge of the jupon. This was worn under a breast-plate which was beginning to replace the mail hauberk. This possibly had a corresponding rear plate. The plate was topped with a surcoat or jupon (more tightly fitting, shorter garment generally without sleeves, although not in the case of the Black Prince’s displayed above his tomb in Canterbury cathedral).

Protection for lower limbs advanced from chain mail to pour point (thickly quilted fabric) through to splinted armour (full plate or white armour by the end of the 14th century).

Feet were covered by mail or articulated sollerets.

Helmet: two types - helm and bascinet

Helm – one piece, reinforced at the front (some with visors developing in middle years of 14th century), becoming more domed/pointed. Worn over a mail hood and a padded cap.

Bascinet – often with exaggerated visor (pig-faced/snout-faced) with a curtain of mail (camail) to sides and rear.

Shield – heater-shaped, becoming smaller over the course of the fourteenth century (wood covered with leather, displaying coat of arms)

Tables and the Battlefield

Terrain

See battle plans.

Initial distance between forces should be 500+ metres

Figure Size/Scale and Colouring

25 mm figures - 50:1

10/15 mm figures – 25:1

Uniforms on both sides were rare with the notable exception of the green and white checks worn by troops from Cheshire. However, the soldiers may have carried some indication of their recruiting captain, possibly adopting heraldic colours, e.g. Arundel’s troops wearing red and white. During Edward I’s Welsh wars, English troops wore an armband bearing the cross of St George.

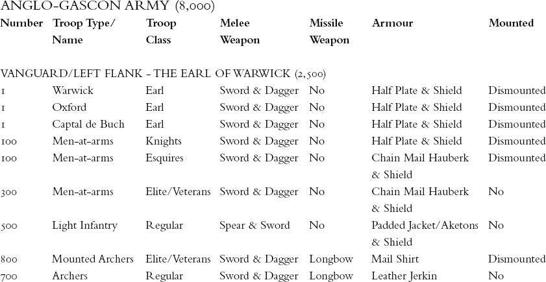

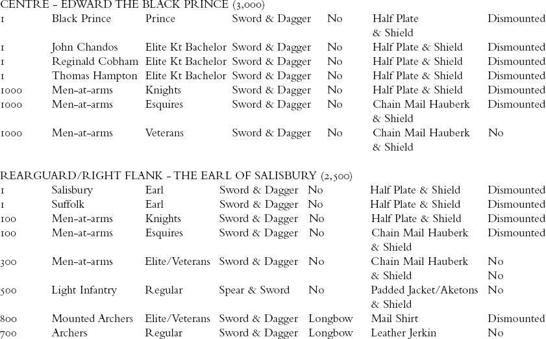

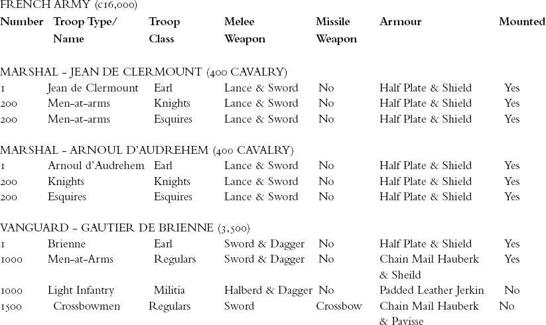

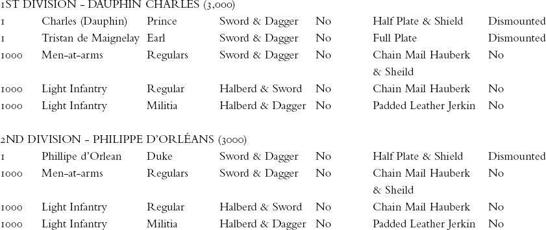

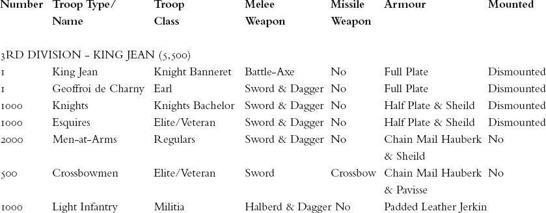

Summary Tables

It may be useful for the purposes of replaying the battle or reworking the battle under differing conditions to construct tables of combatants by troop type to the nearest 50 or 100. Players may wish to distinguish between men-at-arms, esquires, knights banneret, knights bachelor etc. and to attribute elite or veteran status to the remaining men-at-arms and archers. Such decisions will influence the ‘skill levels’ of each figure/troop grouping.

The following categories may be useful:

Section: vanguard, rearguard, centre/1st, 2nd, 3rd division etc.

Troop Type: men-at-arms, archers, crossbowmen, light infantry etc.

Troop Class: Elite, regular, militia/levy

Armour: light, heavy, none, shield

Weapons: sword, longbow, crossbow, halberd, lance etc.

Infantry/Cavalry.

For example:

Further Reading

Primary Sources

Chronicles and Contemporary Texts

For a description of the route of the 1356

chevauchée

from Bergerac see the

Eulogium Historiarum

, iii, ed. F.S. Haydon, London, 1863.

On the battle of Poitiers itself see

The Anonimalle Chronicle

, ed.V.H. Galbraith, Manchester, 1927 which contains unique details of the encounter.

Geoffrey Le Baker,

Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke, 1305-56

, ed. E.M. Thompson, Oxford, 1889 also provides a full account and includes an exhortation made by the prince to his men before the battle.

The verse biography of the prince’s life written c.1380 by Chandos Herald recounts the battle and details the preliminary negotiations although it is most valuable for the Castilian campaign of 1367. Translations are available in the editions by M. Pope and E. Lodge,

Life of the Black Prince by the Herald of Sir John Chandos

, Oxford, 1910 and R. Barber,

The Life and Campaigns of the Black Prince

, Woodbridge, 1986. The most recent edition is D.B. Tyson,

Vie du Prince Noir

, Tübingen, 1975.

The Chronicles of Jean Froissart provide a key insight into the mentality of the fourteenth century Anglo-French aristocracy. There are numerous editions:

Chroniques

, ed. Simeon Luce (SHF), Paris, 1870-present.

Oeuvres

, ed. Kervyn de Lettenhove, Brussels, 1867-77.

The most recent, although heavily expurgated translation into English is G. Brereton,

Froissart: Chronicles

, Harmondsworth, repr. 1978.

For a contemporary guide to chivalry probably written for the Order of the Star see

The Book of Chivalry of Geoffroi de Charny

, ed. and trans. R. Kaueper and E. Kennedy, Philadelphia, 1996.

See also Christine de Pizan,

The Book of Arms and Deeds of Chivalry

, trans. Sumner Willard, ed. Charity Cannon Willard, Pennsylvania, 1999.

Collections of Sources in Translation

C. Allmand,

Society at War. The Experience of England and France During the Hundred Years War

, Edinburgh, 1973, repr. Woodbridge, 1998.

R. Barber,

The Life and Campaigns of the Black Prince

, Woodbridge, 1986.

Clifford J. Rogers,

The Wars of Edward III: Sources and Interpretation

, Woodbridge, 1999 (also contains a selection of important articles on the early stages of the Hundred Years War).

A.R. Myers, ed.,

English Historical Documents

, iv, 1327-1485, London, 1969.

Administrative and Governmental Records

Thomas Rymer,

Foedera, Conventiones, Litterae etc

., London, 1708-9; rev. ed. A. Clarke, F. Holbroke and J. Coley, 4 vols in 7 parts (Record Commission), 1816-69.

Calendar of Close Rolls, Calendar of Patent Rolls, Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem

.

The Parliament Rolls of Medieval England, 1275–1504

, ed. Chris Given-Wilson et al., Woodbridge, 2005.

For the household and estate of the Black Prince see

The Register of Edward the Black Prince

, ed. M.C.B. Dawes, 4 vols, London, 1930-3.

Biographies of the Black Prince

Richard Barber,

Edward Prince of Wales and Aquitaine

, Woodbridge, 1978.

Barbara Emerson,

The Black Prince

, London, 1976.

M. Dupuy,

Le Prince Noir

, Paris, 1970.

David Green,

The Black Prince

, Stroud, 2001.

David Green,

Edward the Black Prince: Power in Medieval Europe

, Harlow, 2007.

John Harvey,

The Black Prince and his Age

, London, 1976.

J. Moisant,

Le Prince Noir en Aquitaine, 1355–6, 1362–70

, Paris, 1894.

Military Studies

Andrew Ayton,

Knights and Warhorses: Military Service and the English Aristocracy under Edward III

, Woodbridge, 1994.

Andrew Ayton and J.L. Price ed.,

The Medieval Military Revolution: State and Society in Medieval and Early Modern Europe

, London and New York, 1995.

J. Barnie,

War in Medieval Society: Social Values and the Hundred Years War

, 1337–99, London, 1974.

Jim Bradbury,

The Medieval Siege

, Woodbridge, 1992.

A.H. Burne,

The Crécy War: A Military History of the Hundred Years War from 1337 to the Peace of Brétigny, 1360

, London, 1955.

Philippe Contamine,

Guerre, état et société à la fin du Moyen Âge. Etudes sur les armées des rois de France, 1337-1494

, Paris, 1972;

War in the Middle Ages

(trans. Michael Jones), Oxford, 1987.

Anne Curry and Michael Hughes, ed.,

Arms, Armour and Fortifications in the Hundred Years War

, Woodbridge, 1994.

Kenneth Fowler,

Medieval Mercenaries

, London, 2000.

H.J. Hewitt, The

Black Prince’s Expedition of 1355–1357

, Manchester, 1958;

The Organization of War under Edward III, 1338–62

, Manchester, 1966.

Maurice Keen ed.,

Medieval Warfare: A History

, Oxford, 1999.