The Articulate Mammal (44 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

In the second extract, the same type of phenomenon occurs, but in a different context.

| T: | WHAT’S THIS BOY DOING? (showing a picture of a boy swimming) |

| P: | O HE’S IN THE SEA. |

| T: | YES. |

| P: | DRIVING … DRIVING. IT’S NOT VERY DEEP. HE’S DRIVING WITH HIS FEET, HIS LEGS. DRIVING. WELL DRIVING, ER DIVING. |

| T: | IN FACT HE’S … |

| P: | SWIMMING. |

| T: | GOOD, WHAT ABOUT THIS ONE? (showing a picture of a boy climbing over a wall) |

| P: | DRIVING, ON A … ON A WALL. |

| T: | HE’S WHAT? |

| P: | DR … DRIVING, HE’S CLIMBING ON A WALL. |

Some of the mistakes in these passages represent an extension of the selection problems seen in ordinary slips of the tongue. That is, some of the same kinds of mistakes occur as in normal speech, but they occur more often. But there is often one major difference: aphasics tend to

perseverate

, they perpetually repeat the same words, again and again, as in the first dialogue above where the patient kept repeating the word RHUBARB. Or, to take another example from the same patient, she was shown a picture of an apple. After some prompting, she said the word APPLE. She was then shown a picture of a blue ball. When asked what it was, she replied without hesitation APPLE. The therapist pointed out that she was confusing the new object with the previous one. ‘Of course, how stupid of me’, replied the patient. ‘This one’s an APPLE. No, no, I didn’t mean that, I mean APPLE!’

Meanwhile, repetitions are relatively unusual among normal people, because they mostly have a very effective ‘wipe the slate clean’ mechanism. As soon as they have uttered a word, the phonetic form no longer remains to clutter up the mind. But aphasics, often to their frustration and despair, keep repeating sounds and words from the sentence before.

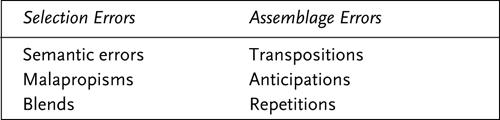

TYPES OF TONGUE SLIP

Broadly speaking, we may categorize the speech errors of normal speakers into two basic types. First, we have those in which a wrong item is chosen, where something has gone wrong with the

selection

process. For example:

DID YOU REMEMBER TO BUY SOME TOOTHACHE? (Did you remember to buy some toothpaste?)

Such errors are perhaps more accurately labelled ‘slips of the brain’.

Second, we find errors in which the correct choice of word has been made, but the utterance has been faultily assembled as in:

SOMEONE’S BEEN WRITENING THREAT LETTERS (Someone’s been writing threatening letters).

Let us look at these two categories,

selection errors

and

assemblage errors

more carefully, and attempt to subdivide them.

Errors in which wrong items have been chosen are most commonly whole word errors. There are three main types:

semantic errors

(or similar meaning errors),

malapropisms

(or similar sound errors) and

blends.

So-called

semantic

or

similar meaning

errors are fairly common. In fact, they are so usual that they often pass unnoticed. We are talking about naming errors in which the speaker gets the general ‘semantic field’ right, but uses the wrong word, as in:

DO YOU HAVE ANY ARTICHOKES? I’M SORRY, I MEAN AUBERGINES.

This kind of mistake often affects pairs of words. People say LEFT when they mean ‘right’, UP when they mean ‘down’, and EARLY instead of ‘late’, as in:

IT’S SIX O’CLOCK. WON’T THAT BE TOO EARLY TO BUY BREAD?

Mistakes like this occur repeatedly in the speech of some aphasics, and in its extreme form the general condition is sometimes rather pompously labelled ‘conceptual agrammatism’ (Goodglass 1968). Such patients confuse words like YESTERDAY, TODAY and TOMORROW. They seem able to find names connected with the general area they are talking about, but unable to pinpoint particular words within it, so that a ‘garden roller’ could be called a LAWN MOWER, a ‘spade’ may be called a FORK, and a ‘rake’ may be called a HOE. A mistake like this occurred in one of the aphasic passages quoted above, when the patient said DIVING instead of ‘swimming’.

The second type of word selection error, so-called

malapropisms

occur when a person confuses a word with another, similar sounding one. The name comes from Mrs Malaprop, a character in Richard Sheridan’s play

The Rivals

, who continually confused words which sounded alike, as in:

SHE’S AS HEADSTRONG AS AN ALLEGORY ON THE BANKS OF THE NILE (She’s as headstrong as an alligator on the banks of the Nile).

A NICE DERANGEMENT OF EPITAPHS (A nice arrangement of epithets).

Not only in Sheridan’s play, but in real life also, the results are sometimes hilarious, as when an angry woman demanded:

WHAT ARE YOU INCINERATING? (insinuating)

Equally funny was a man’s statement that he had NUBILE TOES meaning ‘mobile’ ones – though it is of course impossible to tell sometimes, as in this case, whether he was genuinely confused about the meaning of NUBILE.

So far, we have mentioned selection errors connected with meaning, and selection errors connected with the sound of the word. But it would be a mistake to assume that we can easily place mistakes into one or the other category. Often the two overlap. Although children’s mistakes are usually purely phonetic ones, as in:

MUSSOLINI PUDDING (semolina pudding)

NAUGHTY STORY CAR PARK (multi-storey car park),

the majority of adult ones have some type of semantic as well as phonetic link as when a lady lecturer claimed that:

YOU KEEP NEWBORN CHICKS WARM IN AN INCINERATOR (You keep newborn chicks warm in an incubator).

In addition to the phonetic similarity, both words are connected with the idea of heat. Another example is the statement:

YOU GO UNDER A RUNWAY BRIDGE (You go under a railway bridge).

Here, in addition to the similar sounds, both words describe a track for a means of transport. Yet another example is the error:

COMPENSATION PRIZE (consolation prize).

However, the semantic connection does not always have to be between the two words that are being confused. Sometimes the intruding idea comes in from the surrounding context, as in the statement:

LEARNING TO SPEAK IS NOT THE SAME THING AS LEARNING TO TALK (Learning to speak is not the same thing as learning to walk).

Another example of this type of confusion was uttered by a nervous male involved in a discussion on BBC’s

Woman’s Hour

about a cat who never seemed to sleep, because it was perpetually chasing mice. He said:

HOW MANY SHEEP DOES THE CAT HAVE IN ITS HOUSE THEN? I’M SORRY, I MEAN MICE, NOT SHEEP.

The speaker correctly remembered that he was talking about an animal of some kind, but the animal had somehow become contaminated by the sound of the word SLEEP, resulting in SHEEP! He may also have been influenced by the fact that humans reputedly count sheep jumping over fences in order to get to sleep.

The third type of selection error, so-called

blends

, are an extension and variation of semantic errors. They are fairly rare, and occur when two words are ‘blended’ together to form one new one. For example:

NOT IN THE SLEAST

is a mixture of ‘slightest and least’. And:

PLEASE EXPLAND THAT

is a mixture of ‘explain and expand’. A rather more bizarre example of a blend occurs in the first passage of aphasic speech quoted on p. 217. The patient had been talking about RHUBARB, and was trying to think of the word APPLE. What came out was a mixture of the two, RABBIT! Such mixes are also known as

contaminations

since the two words involved ‘contaminate’ one another. Often, if the speaker is quite well, both the items chosen are equally appropriate. The speaker seems to have accidentally picked two together – or rather failed to choose between two equally appropriate words in time. She has not so much picked the wrong word, as not decided which of the right ones she needed.

Sometimes two items are intentionally blended together in order to create a new word. Lewis Carroll makes Humpty Dumpty explain in

Alice Through the Looking Glass

that SLITHY means ‘lithe and slimy’, commenting, ‘You see, it’s like a portmanteau – there are two meanings packed up into one word’ – though Lewis Carroll’s made-up words may not be as intentional as they appear. Apparently, he suffered from severe migraine attacks, and many of his strange neologisms are uncannily like the kind of temporary aphasia produced by some migraine sufferers (Livesley 1972). Perhaps better examples of intentional blends are SMOG from ‘smoke and fog’, and BRUNCH from ‘breakfast and lunch’. Occasional parallels of this type can be spotted between slips of the tongue and language change (Aitchison 2001).

Let us now turn to

assemblage errors

– errors in which the correct word choice has been made, but the items chosen have been faultily assembled. There are three main types: transpositions, anticipations and repetitions, which may affect words, syllables or sounds.

Transpositions

are not, on the whole, very common (Cohen 1966; Nooteboom 1969). Whole words can switch places, as in:

DON’T BUY A CAR WITH ITS TAIL IN THE ENGINE (Don’t buy a car with its engine in the tail).

I CAN’T HELP THE CAT IF IT’S DELUDED (I can’t help it if the cat’s deluded).

and so can syllables:

I’D LIKE A VIENEL SCHNITZER (I’d like a Viener schnitzel).

But perhaps the best known are the sound transpositions known as spoonerisms. These are named after a real-life person, the Reverend William A. Spooner, who was Dean and Warden of New College, Oxford, around the turn of the century. Reputedly, he often transposed the initial sounds of words, resulting in preposterous sentences, such as:

THE CAT POPPED ON ITS DRAWERS (The cat dropped on its paws).

YOU HAVE HISSED ALL MY MYSTERY LECTURES (You have missed all my history lectures).

YOU HAVE TASTED THE WHOLE WORM (You have wasted the whole term).

However, there is something distinctly odd about these old spoonerisms. One suspects that the utterances of the Reverend Spooner were carefully prepared for posterity, probably by his students. The odd features are that they always make sense, they affect only initial sounds, and there is no discernible phonetic reason for the transposed sounds. In real life, spoonerisms do not usually make sense, as in:

TILVER SILLER (silver tiller).

They can affect non-initial sounds, as in:

A COP OF CUFFEE (a cup of coffee).

And they frequently occur between phonetically similar sounds, as

LEAK WINK (weak link).

Anticipations

, particularly sound anticipations, are the most widespread type of assemblage error. Here, a speaker anticipates what he is going to say by bringing in an item too early. It is not always possible to distinguish between

anticipations and potential transpositions if the speaker stops himself halfway through, after realizing his error. This may partially account for the high recorded proportion of anticipations compared with transpositions. For example, the following could be a prematurely cut off transposition:

I WANT YOU TO TELL MILLICENT … I MEAN, I WANT YOU TO TELL MARY WHAT MILLICENT SAID.

But the following sound anticipations are clearly just simple anticipations. A participant in a television discussion referred, much to his embarrassment, to:

THE WORST GERMAN CHANCELLOR (The West German Chancellor).

Here he had anticipated the vowel in GERMAN. The same thing happened to the man who, interrupting over-eagerly, begged to make:

AN IMPOITANT POINT (an important point).

Repetitions

(or

perseverations

) are rather rarer than anticipations, though commoner than transpositions. We find repeated words, as in:

A: ISN’T IT COLD? MORE LIKE A SUNDAY IN FEBRUARY.

B: IT’S NOT TOO BAD – MORE LIKE A FEBRUARY IN MARCH I’D SAY (It’s not too bad – more like a Sunday in March).

An example of a repeated sound occurred when someone referred to:

THE BOOK BY CHOMSKY AND CHALLE (Chomsky and Halle).

perhaps an indication of the mesmerizing effect of Chomsky on a number of linguists!

We have now outlined the main types of selection and assemblage errors: