Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

The Articulate Mammal (20 page)

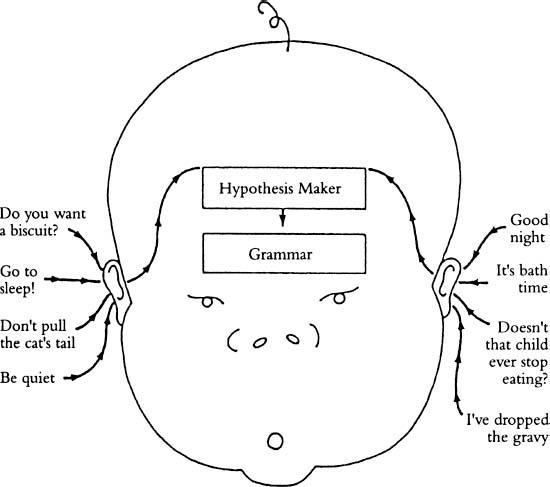

Children, according to Chomsky (1965), construct an internalized grammar in the same way. They look for regularities in the speech they hear going on around them, then make guesses as to the rules which underlie the patterns. Their first guess will be a simple one. The second amended hypothesis will be more complex, the third, more elaborate still. Gradually their mental grammar will become more sophisticated. Eventually their internalized rules will cover all the possible utterances of the language. Fodor (1966: 109) described the situation clearly:

Like the scientist, the child finds himself with a finite body of observations, some of which are almost certain to be unsystematic. His problem is to discover regularities in these data that, at the very least, can be relied upon to hold however much additional data is added. Characteristically the extrapolation takes the form of the construction of a theory that simultaneously marks the systematic similarities among the data at various levels of abstraction, permits the rejection of some of the observational data as unsystematic, and automatically provides a general characterization of the possible future observations.

If this hypothesis-testing view of language acquisition is correct, children must be endowed with an innate

hypothesis-making device

which enables them, like miniature scientists, to construct increasingly complex hypotheses.

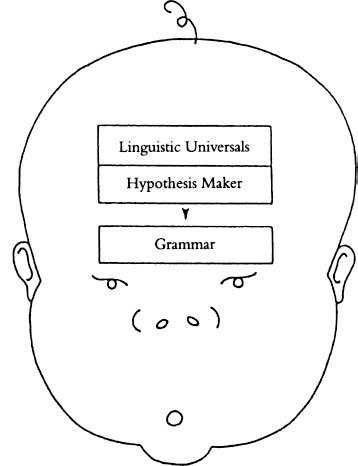

However, there are a number of differences between a linguist working on an unknown language, and a child acquiring language for the first time. The linguist has always had considerably more help at his disposal. He could say to a native speaker of the language he is working on, ‘Does LEGLESS DADDYLONG-LEGS make sense?’ ‘Is ATE UP IT grammatical?’ ‘Is PLAYING CARDS ambiguous?’ and so on. The child cannot do this. Yet the amazing fact remains: it is the child who acquires the complete grammar. No linguist has ever written a perfect grammar of any language. This suggests that by itself, an internal hypothesis-making device is not sufficient to account for the acquisition of language. The child must have some extra knowledge at his disposal. It cannot be knowledge about any particular language because babies learn all languages with equal ease. A Chinese baby brought up in England will learn English as easily as an English baby in China will learn Chinese. The wired-in knowledge must, therefore, said Chomsky, consist of

language universals

. Children learn language so fast and efficiently because they ‘know’ in outline what languages look like. They know what is, and what is not, a possible language. All they have

to discover is

which

language they are being exposed to. In Chomsky’s words, his theory:

attributes tacit knowledge of linguistic universals to the child. It proposes that the child approaches the data with the presumption that they are drawn from a language of a certain antecedently well-defined type, his problem being to determine which of the (humanly) possible languages is that of the community in which he is placed.

(Chomsky 1965: 27)

The child is perhaps like a pianist waiting to sight-read a piece of music. The pianist will know in advance that the piece will have a rhythmic beat, but she will not know whether it is in two, three or four time until she sees it. She will know that the notes are within a certain range – but she will not know in what order or combinations they come. But it is not very satisfactory to speak airily of ‘innate linguistic universals’. What

are

these shadowy phenomena?

Language universals, Chomsky suggested (1965), are of two basic types,

substantive

and

formal

. Substantive universals represent the fundamental ‘building blocks’ of language, the substance out of which it is made, while formal universals are concerned with the form or shape of a grammar. An analogy might

make this distinction clearer. If, hypothetically, Eskimos were born with an innate knowledge of igloo-building they would have

two

kinds of knowledge. On the one hand, they would know in advance that the

substance

out of which igloos are made is ice and snow, just as thrushes automatically know that their nests are made of twigs, not bricks or worms or glass. On the other hand, their innate knowledge of igloo-building would include the information that igloos are round in

shape

, not square or diamond-shaped or sausage-like, just as thrushes instinctively build round nests, not ones shaped like bathtubs.

To return to the substantive universals of human language, a child might know instinctively the possible set of sounds to be found in speech. She would automatically reject sneezes, belches, hand-clapping and foot-stamping as possible sounds, but accept B, O, G, L, and so on. She would dismiss PGPGPG as a possible word, but accept POG, PIG, PEG or PAG.

But the idea of

substantive

universals was not particularly new. For a long time linguists had assumed that all languages have nouns, verbs and sentences even though the exact definitions of these terms is in dispute. And for a long time linguists have been trying to identify a ‘universal phonetic alphabet’ which ‘defines the set of possible signals from which signals of a particular language are drawn’ (Chomsky 1972b: 121). Such a notion is not very surprising, since humans all possess similar vocal organs. More revolutionary were the

formal

universals proposed by Chomsky. These were concerned with

the form or shape of a grammar, including the way in which the different parts relate to one another.

According to Chomsky, children would ‘know’ in advance how their internalized grammar must be organized. It must have a set of

phonological

rules for characterizing sound patterns and a set of

semantic

rules for dealing with meaning, linked by a set of

syntactic

rules dealing with word arrangement.

Furthermore, children would instinctively realize that in its rules language makes use of

structure-dependent

operations. This, as noted in

Chapter 1

involves at least two types of knowledge: first, an understanding of hierarchical structure – the notion that several words can fill the same slot as one:

Second, it involves a realization that each slot functions as a unit that can be moved around (though with minor extra adjustments):

Furthermore (as outlined in

Chapter 1

) Chomsky at one time assumed that every sentence had an ‘inner’ hidden

deep structure

and an outer manifest

surface structure

. The two levels of structure were linked by rules known as

transformations

. As he explained:

The grammar of English will generate, for each sentence, a deep structure, and will contain rules showing how this deep structure is related to a surface structure. The rules expressing the relation of deep and surface structure are called ‘grammatical transformations’.

(Chomsky 1972b: 166)

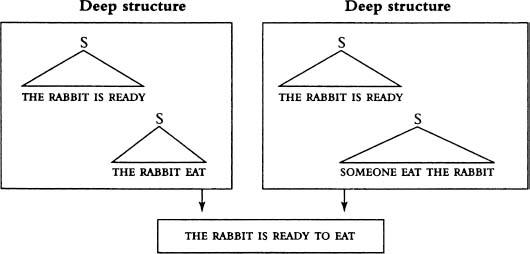

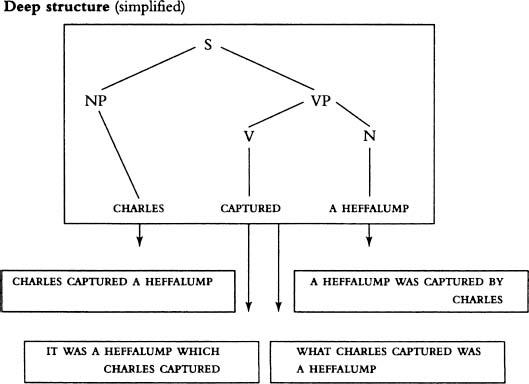

According to this view, several sentences that were quite different on the surface could be related to

one

deep structure. The four sentences:

CHARLES CAPTURED A HEFFALUMP.

A HEFFALUMP WAS CAPTURED BY CHARLES.

IT WAS A HEFFALUMP WHICH CHARLES CAPTURED.

WHAT CHARLES CAPTURED WAS A HEFFALUMP.

were all related to a similar underlying structure.

Alternatively, different deep structures could undergo transformations which made them similar on the surface, as in:

THE RABBIT IS READY TO EAT.

which could either mean that the rabbit was hungry, or that it was about to be eaten.