The Arithmetic of Life and Death (19 page)

Read The Arithmetic of Life and Death Online

Authors: George Shaffner

Tags: #Philosophy, #Movements, #Phenomenology, #Pragmatism, #Logic

One chance in fifteen is not a huge probability. But it is significant. If you are lucky enough to live to be eighty years old, then about 12,000,000 people will die from homicide, suicide, and accident within your lifetime. Moreover, each one of them will lose an average of 23.9 years of potential life.

*

Therefore, if you are unlucky enough to die by misadventure, then you are likely to forgo some 30 percent of your life expectancy. It could be more, especially if you are male. So it would seem prudent to determine what you may be able to do to minimize your chances of an unexpected or violent end.

Without question, the very best way to reduce the likelihood of an untimely death is to be a woman. Even if you were not born a woman, then you may wish to consider behaving like one. Presumably, this would mean doing the little things, like reading the label on the bottle before mixing your heart medicine with bourbon, or not swimming across the flood-swollen river when the water temperature is only fifty degrees Fahrenheit (ten degrees on the centigrade scale) just to prove that you can do it, or not relying on lethal weapons to resolve differences of opinion.

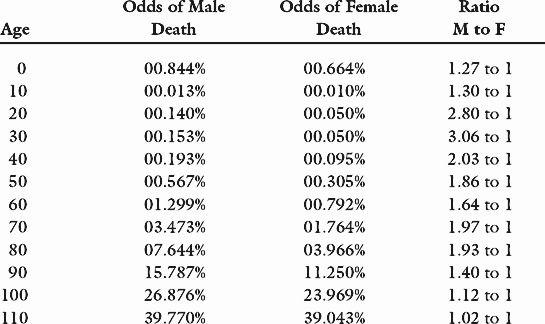

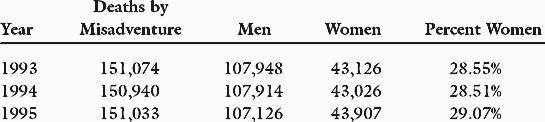

Whatever it is that women do and men don’t, or vice versa, women lead less perilous lives. From 1993 to 1995, women, who made up slightly more than half of the population, accounted for only 29 percent of all deaths by accident, homicide, and suicide:

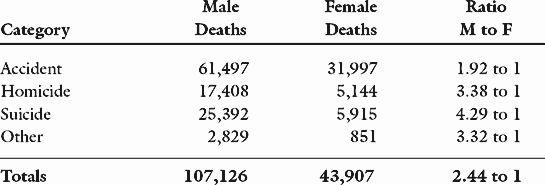

In all three years, and presumably in most of the years before that, men were more than twice as likely as women to die before their time. Apparently, this was no accident. In 1995, men were more than three times as likely to die by homicide and more than four times as likely to die by their own hand:

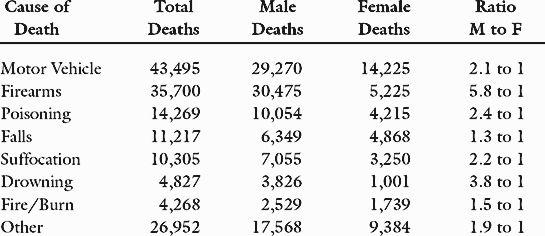

At a more detailed level of misadventure, forthrightly labeled cause of death, women were also less likely to die in every major category:

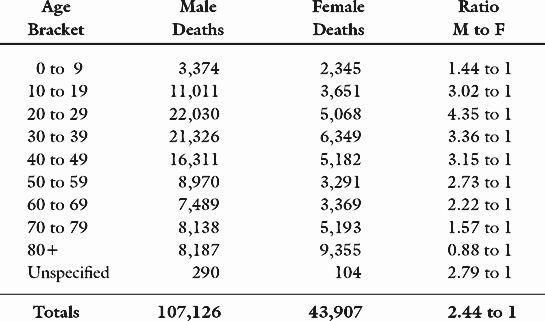

Not all of the news is bad for men all of the time, though. In one age bracket, eighty and older, women are more likely than men to die by misadventure. The reason, of course, is that the majority of men are already dead, especially the risk takers. In all of the younger age brackets except two, men are two to four times as likely as women to die an untimely death:

By now, a fairly clear course has been charted for those seeking to minimize the possibility of an untimely demise. Although some factors may be generally beyond your control, such as being booked on the

Titanic

on her maiden voyage, there are a few simple precautions that can dramatically improve your odds of dying of heart disease or cancer, both of which are considered to be natural causes. Those most likely to be effective are:

- If you are male, then behaving like a woman in matters of risk could reduce your odds of premature death by almost 60 percent (from about 107,663 per year to about 43,353). Moreover, if every man could do this faithfully every single day, then the national death toll by misadventure would be cut from about 151,000 to around 87,000 per year, a decrease of more than 42 percent.

- If you are already a woman, or if you are a man and you cannot bring yourself to act like a woman, then pretend to be old. Older people, especially those in their sixties, are more cautious than younger people. If you are a man in your twenties, this simple leap of conservatism could cut your chances of an untimely end by as much as 66 percent (100 percent—[7,489 22,030]), which would be nearly as effective as acting like a woman. (A male in his twenties who behaved exactly like a female in her twenties would cut his chances of premature death by 77 percent, which is equal to 100 percent—[5,068 ÷ 22,030].)

- If you consider gender to be fate rather than choice, and if you insist on acting your age, then at least stay out of range. In 1995, 35,279 Americans died from gunshots, which was almost 24 percent of all deaths by misadventure. Of those, more than half were by suicide.

- If you must assert your Constitutional right to carry one of the nation’s 200 million guns, then at least refuse to commit suicide with it, or by any other means. This singular act of personal hygiene could reduce your chances of early death by 21 percent (31,307 ÷ 151,033).

- Regardless of your sex and age, do whatever you can to avoid being murdered. Homicides accounted for about 15 percent of all deaths by misadventure in 1995 (22,552 ÷ 151,033).

- Do not drive while intoxicated or travel in the company of those who commit this crime. If everyone, men and women alike, could cooperate in this one endeavor, then assuming that at least 40 percent of all

fatal traffic accidents are caused by drunk drivers, deaths from misadventure could be reduced by more than 11 percent (43,495 × .4 ÷ 151,033) per year.

Of course, nobody can completely eliminate the possibility of death by misadventure. There are too many dangers in life, and the day-to-day living of it requires that we encounter too many of them too often for all of us to be safe all of the time. However, by doing just a few simple things, you can significantly increase the probability that you will live a long, long time.

*

In 1995, the 151,033 unfortunate souls who died before their time lost an aggregate of 3,609,454 years of potential life, which is an average of 23.9 each.

31

Life Expectancy

“Hello darkness, my old friend

I’ve come to talk with you again.”

— PAUL SIMON

A

baby born in the United States in the year 1900 had a life expectancy of about forty-eight years. By 1998, this figure had increased to about seventy-seven years, which is a testimony to advances in diet, hygiene, education, medicine, and a thousand technologies. It may also be something of a puzzlement to anyone who is older than seventy-seven and not dead yet.

The solution to the puzzle is that life expectancy at birth and life expectancy later in life are two entirely different matters. Cecilia Sharpe is a fine example. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, a baby born in the United States in 1950, the year of Cecilia’s birth, could expect to live until the age of sixty-eight. However, Cecilia’s life expectancy is not age sixty-eight. Nor is it the current figure of seventy-seven. There are several reasons why:

- The life expectancy estimate of seventy-seven years is an average figure which applies only to babies born in the United States in 1998.

- Cecilia is a woman, which means that she is likely to outlive the average by three years (men live about three years less than the average, women about three years more than the average).

- Cecilia is not dead yet. Unfortunately, a lot of people born in 1950 already are dead. Their deaths were factored into the original life expectancy estimate of sixty-eight years for people born that year. Since they died before age sixty-eight, and since age sixty-eight was an average, then they allowed others to die after the age of sixty-eight.

- So, since Cecilia has not died, her life expectancy has increased considerably beyond the initial estimate.

In fact, according to the Life Expectancy Tables from the U.S. Internal Revenue Service, people who were born in 1950 and who were still alive in 1998 had an average life expectancy of age eighty-three, a fifteen-year advance over their expectancy at birth. Since Cecilia is female, her current life expectancy is closer to eighty-six years, which means that the most likely year of her death is the year 2036.

Cecilia’s estranged husband is not likely to be so lucky. He was born in 1948, just two years before Cecilia. But he is a male and he is a smoker. That means that his life expectancy is more likely to be around seventy-six years, which is his current age of fifty, plus thirty-four years for being not dead yet, but minus three years for being male and minus another five years for being a habitual smoker. Thus, the mostly likely year of his death is predicted to be

the year 2024, twelve years before Cecilia and, in Gwendolyn Sharpe’s mind, perhaps a small measure of justice.

But Gwen’s father is still not likely to die in the year 2024, and her mother is not likely to die in the year 2036 either. That is because according to actuarial tables published by Faber and Wade, there is no year in which death is as likely as continued life, at least until the age of 115. Until that time, the probability of death occurring in any one year varies from a low of 0.009 percent (about one chance in 11,000) for a girl of age eleven to a high of 46.5 percent for either gender at age 114. In most of the years in between, the odds that a man will die in any given year are two to three times as high as they are for a woman of the same age: