The Arithmetic of Life and Death (18 page)

Read The Arithmetic of Life and Death Online

Authors: George Shaffner

Tags: #Philosophy, #Movements, #Phenomenology, #Pragmatism, #Logic

If a single PLL Occupant manages to impede ten cars by a minute each, let’s say, then the total loss is only ten minutes and tempers are likely to remain in check. But the hardcore PLLO are not visitors to the left-hand lane, they are inhabitants. If an ardent PLLO commuter can delay one

hundred cars by an average of three minutes each way, then the daily loss will be ten hours per day and the aggregate annual delay will be 2,500 hours. That equates to more than 300 workdays of wasted road time per year per practicing PLL Occupant. If someone misses a job interview or is late for an important sales call, or if an accident is caused by someone who is in too much of a hurry to get around the PLLO, then the potential loss can be much larger.

No one knows why so many ordinary citizens have volunteered for active duty with the PLLO. Possibly, they believe that slower traffic is safer traffic, even if too many cars are following much too closely and others are being passed on the right where the blind spot is most severe. Perhaps the PLLO want to live life in the fast lane, even if they don’t have the speed. Maybe they believe that it is their right to drive in the left-hand lane, regardless of the impact on fellow drivers.

However, there is an actual cost incurred by the act of moving out of the left lane so that others can pass. If, for instance, an average PLL Occupant is driving at 50 miles per hour, then he (or she) will travel about 220 feet every three seconds. If the PLL Occupant takes three seconds to move fifteen feet to the right to get out of the way of faster traffic, then, by the Pythagorean Theorem,

*

the net distance

traveled will be only about 219.5 feet. The other six inches will be consumed in moving into the adjacent lane.

So our sample PLL Occupant will have been delayed by the time it takes to cover a distance of six inches. At fifty miles per hour, that equates to a time loss of approximately .007 seconds. If the PLLO moves back into the left-hand lane after faster traffic has passed, then the total time loss is .014 seconds.

*

It takes just 0.014 seconds to get out of the way. Therefore, something like one-seventieth of a second is a fairly reasonable estimate of the cost of highway courtesy. It means that seventy similar acts of highway courtesy will take a total of one second.

Most acts of courtesy take more time, but not much more. A door can be opened in a second or two. A plastic container can be picked up and thrown in a proper receptacle in a few more. It may take ten or fifteen seconds to let a pedestrian cross the road.

But the return on a few seconds of courtesy can be significant. People, perhaps a lot of people, will get where they are going sooner and more safely. The landscape will be less dangerous and more appealing to the eye. Occasionally, someone may even get the impression that someone else cares, even if it’s only for 0.014 seconds.

*

According to Pythagoras, the length of the hypotenuse of a right triangle squared is equal to the total of the lengths of the other two sides squared. The 220 feet traveled while moving into the right lane is the hypotenuse, which is 48,400 when squared. The short side of the triangle is the 15 feet in distance from the left lane to the right lane, which is 225 when squared. To get the third side of the triangle, which is the net forward distance traveled, we subtract 225 from 48,400 to get 48,175. Then we take its square root, which is 219.49 feet. That means that the PLL Occupant will have traveled 6.12 inches (.51 feet) less toward his destination by virtue of the detour into the right-hand lane.

*

A car traveling 50 miles per hour covers 264,000 feet per hour (50 times 5,280). That is equivalent to 73.33 feet per second (by dividing by the number of seconds in an hour, which is 3,600). Thus, at 50 miles per hour, 6.12 inches is traveled in approximately .007 seconds.

29

The Tailgater’s Advantage

“As if there were safety in stupidity alone.”

— HENRY DAVID THOREAU

A

ccording to the National Safety Council, there were 10.7 million automobile accidents in the United States in 1995. More than 1.4 million of them resulted in disabling injury or death. Rear-end collisions accounted for about one in every six accidents, or more than 1.7 million accidents every year, many of them of the disabling variety, some of them fatal.

Rear-enders ought to be among the easiest of accidents to eliminate since drivers need to do no more than follow each other at a safe distance. But tailgating seems to be growing in popularity, so there must be a payoff.

The California Department of Motor Vehicles recommends a minimum following distance of three seconds for any vehicle. At a speed of sixty miles an hour, that

equates to 264 feet, or around 16 car lengths. But Billy Ray DeNiall, Reginald’s younger son and a model tailgater, routinely cuts that distance by two-thirds, to only 88 feet. He must have excellent reflexes because he has just one second—instead of three—to observe any dramatic change in the vehicle in front of him, then decide what to do, and then get it done.

If Billy Ray were a typically cautious driver, he would have a fifteen-minute commute to school. However, as a result of his courageous tailgating, Billy Ray now gets to school two full seconds sooner. Therefore, he has reduced his daily commute time to an economical twenty-nine minutes and fifty-six seconds, an impressive savings of two-tenths of 1 percent.

Now we know the tailgater’s advantage. But do we know what the real risk is?

In the real world, there may be many occasions when not even one second of reaction time is available to the committed tailgater. That’s because vehicles have variable stopping distances. In tests of more than 200 vehicles, the magazine

Motor Trend

reports stopping distances from 60 miles per hour that vary from as little as 102 feet (a Toyota sports car) to as much as 167 feet (a Dodge pickup truck). (Those figures were for new vehicles, almost all of which had antilock brakes and were in perfect repair. Older vehicles, especially pickup trucks, vans, and SUVs, can take more than 200 feet to stop from 60 miles per hour, and more yet if their brakes are worn.)

If Billy Ray has the misfortune to close in on the Toyota in his Dodge pickup, he will no longer have even a second to react. That is because it will take his vehicle about

sixty-five feet longer to stop than the vehicle in front of him. In fact, Billy Ray’s reaction time will be reduced to .26 seconds! That is too little time to have any hope of evading collision. Sadly, Billy Ray is more likely to rear-end the Toyota at as much as thirty miles per hour, a speed at which collisions can be fatal.

Most weekends, you can see plenty of nose-to-tail driving at any automobile race. Called “drafting,” it provides an aerodynamic advantage to both the leading and trailing drivers. But drafting is done only in a highly controlled race environment, all of the drivers are skilled professionals, they drive homogeneous and specially prepared automobiles, and there is a crew of highly trained mechanics standing by all the time to make sure that everything is working as well as possible. Even so, hardly a race goes by without serious accident, which is why there is usually a mobile medical team on site.

In normal driving, there is no advantage to drafting, aerodynamic or otherwise. The streets are filled with amateur, distracted, and disinterested drivers. Their vehicles span a broad spectrum of specification and performance. Many of the vehicles are old, many are in a poor state of repair, and pit crews and medical teams are not standing by.

Even though they have less to lose, old people rarely tailgate. That is because they have had to learn the rules of risk and return in order to become old people. One of those rules is: Unless under gunpoint, never take a 20,000-to-one long shot.

Tailgating is the twentieth-century archetype of the dimwit decision. The upside is tiny; two seconds or so. If you tailgate to and from work every day for fifty years, including

weekends, then you can save a total of about 73,000 seconds, or around twenty hours.

If you are twenty-five years old and you expect to live to be seventy-five, then a fatal rear-ender could cost you more than 1.57 billion seconds of breath, which is more than 438,000 hours. The downside is 21,000 times the upside. The downside is that you could lose your life.

“There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

— WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

30

Death by Misadventure

“Carriages without horses shall go,

And accidents fill the world with woe.”

—ANONYMOUS

A

ll human beings have fears. As if Nature hasn’t supplied us with enough of them, such as hurricanes, killer bees, and

e. coli

, we have invented many more. Assault weapons, nuclear waste, Jet Skis, garbage disposals, and fast food come immediately to mind. Because there are so many natural and man-made dangers out there, and because we are reminded of them with such regularity by our chums in the media, one of the commonest fears of our time is that we will die before our time.

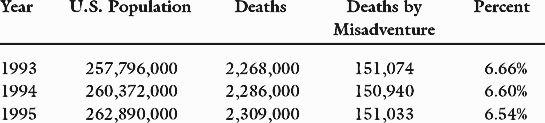

Statistics compiled by the National Center of Injury Prevention Control (which is a relatively new part of the National Centers for Disease Control) show that this fear is not completely unfounded. In each of the years from 1993 through 1995, the first three years in which mortal injury

results were compiled by the CDC, 151,000 Americans, plus or minus 74, died from firearms, traffic accidents, poisoning, suffocation, drowning, falls, fire, machinery, over-exertion, and other causes.

In the same three-year period, the total number of deaths in the United States averaged very near 2.3 million annually according to the National Funeral Directors Association. So, from 1993 to 1995, about 6.6 percent of those who expired, or about one in fifteen, did so “before their time”: