The Andromeda Strain (20 page)

Read The Andromeda Strain Online

Authors: Michael Crichton

Tags: #Thrillers, #Science Fiction, #Suspense, #High Tech, #Fiction

The rat looked around the room, sniffed the air, and made some stretching movements with its neck. A moment later it flopped over onto its side, kicked once, and was still.

It had happened with astonishing speed. Hall could hardly believe it had happened at all.

“My God,” Stone said. “What a time course.”

“That will make it difficult,” Leavitt said.

Burton said, “We can try tracers …”

“Yes. We’ll have to use tracers on it,” Stone said. “How fast are our scans?”

“Milliseconds, if necessary.”

“It will be necessary.”

“Try the rhesus,” Burton said. “You’ll want a post on it, anyway.”

Stone directed the mechanical hands back to the wall, opening another door and withdrawing a cage containing a large brown adult rhesus monkey. The monkey screeched as it was lifted and banged against the bars of its cage.

Then it died, after flinging one hand to its chest with a look of startled surprise.

Stone shook his head. “Well, at least we know it’s still biologically active. Whatever killed everyone in Piedmont is still there, and still as potent as ever.” He sighed. “If potent is the word.”

Leavitt said, “We’d better start a scan of the capsule.”

“I’ll take these dead animals,” Burton said, “and run the initial vector studies. Then I’ll autopsy them.”

Stone worked the mechanical hands once more. He picked up the cages that held the rat and monkey and set them on a rubber conveyor belt at the rear of the room. Then he pressed a button on a control console marked AUTOPSY. The conveyor belt began to move.

Burton left the room, walking down the corridor to the autopsy room, knowing that the conveyor belt, made to carry materials from one lab to another, would have automatically delivered the cages.

Stone said to Hall, “You’re the practicing physician among us. I’m afraid you’ve got a rather tough job right now.”

“Pediatrician and geriatrist?”

“Exactly. See what you can do about them. They’re both in our miscellaneous room, the room we built precisely for unusual circumstances like this. There’s a computer linkup there that should help you. The technician will show you how it works.”

14

Miscellaneous

HALL OPENED THE DOOR marked MISCELLANEOUS, thinking to himself that his job was indeed miscellaneous—keeping alive an old man and a tiny infant. Both of them vital to the project, and both of them, no doubt, difficult to manage.

He found himself in another small room similar to the control room he had just left. This one also had a glass window, looking inward to a central room. In the room were two beds, and on the beds, Peter Jackson and the infant. But the incredible thing was the suits: standing upright in the room were four clear plastic inflated suits in the shape of men. From each suit, a tunnel ran back to the wall.

Obviously, one would have to crawl down the tunnel and then stand up inside the suit. Then one could work with the patients inside the room.

The girl who was to be his assistant was working in the room, bent over the computer console. She introduced herself as Karen Anson, and explained the working of the computer.

“This is just one substation of the Wildfire computer on the first level,” she said. “There are thirty substations throughout the laboratory, all plugging into the computer. Thirty different people can work at once.”

Hall nodded. Time-sharing was a concept he understood. He knew that as many as two hundred people had been able to use the same computer at once; the principle was that computers operated very swiftly—in fractions of a second—while people operated slowly, in seconds or minutes. One person using a computer was inefficient, because it took several minutes to punch in instructions, while the computer sat around idle, waiting. Once instructions were fed in, the computer answered almost instantaneously. This meant that a computer was rarely “working,” and by permitting a number of people to ask questions of the computer simultaneously, you could keep the machine more continuously in operation.

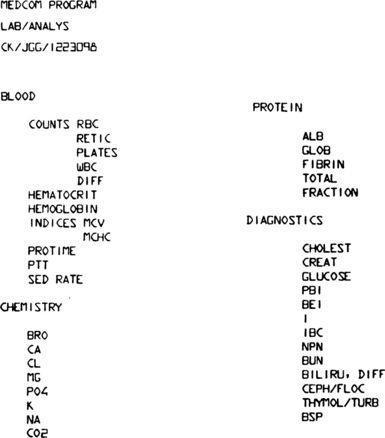

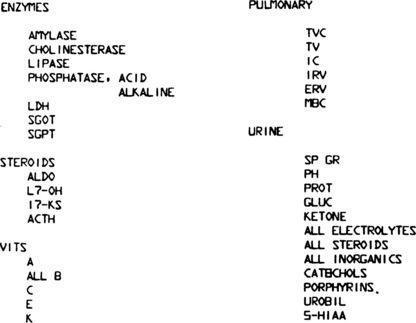

“If the computer is really backed up,” the technician said, “there may be a delay of one or two seconds before you get your answer. But usually it’s immediate. What we are using here is the MEDCOM program. Do you know it?”

Hall shook his head.

“It’s a medical-data analyzer,” she said. “You feed in information and it will diagnose the patient and tell you what to do next for therapy, or to confirm the diagnosis.”

“Sounds very convenient.”

“It’s fast,” she said. “All our lab studies are done by automated machines. So we can have complex diagnoses in a matter of minutes.”

Hall looked through the glass at the two patients. “What’s been done on them so far?”

“Nothing. At Level I, they were started on intravenous infusions. Plasma for Peter Jackson, dextrose and water for the baby. They both seem well hydrated now, and in no distress. Jackson is still unconscious. He has no pupillary signs but is unresponsive and looks anemic.”

Hall nodded. “The labs here can do everything?”

“Everything. Even assays for adrenal hormones and things like partial thromboplastin times. Every known medical test is possible.”

“All right. We’d better get started.”

She turned on the computer. “This is how you order laboratory tests,” she said. “Use this light pen here, and check off the tests you want. Just touch the pen to the screen.”

She handed him a small penlight, and pushed the START button.

The screen glowed.

Hall stared at the list. He touched the tests he wanted with the penlight; they disappeared from the screen. He ordered fifteen or twenty, then stepped back.

The screen went blank for a moment, and then the following appeared:

TESTS ORDERED WILL REQUIRE FOR EACH

SUBJECT

20 CC WHOLE BLOOD

L0 CC OXALATED BLOOD

L2 CC CITRATED BLOOD

15 CC URINE

The technician said, “I’ll draw the bloods if you want to do physicals. Have you been in one of these rooms before?”

Hall shook his head.

“It’s quite simple, really. We crawl through the tunnels into the suits. The tunnel is then sealed off behind us.”

“Oh? Why?”

“In case something happens to one of us. In case the covering of the suit is broken—the integrity of the surface is ruptured, as the protocol says. In that case, bacteria could spread back through the tunnel to the outside.”

“So we’re sealed off.”

“Yes. We get air from a separate system—you can see the thin lines coming in over there. But essentially you’re isolated from everything, when you’re in that suit. I don’t think you need worry, though. The only way you might possibly break your suit is to cut it with a scalpel, and the gloves are triple-thickness to prevent just such an occurrence.”

She showed him how to crawl through, and then, imitating her, he stood up inside the plastic suit. He felt like some kind of giant reptile, moving cumbersomely about, dragging his tunnel like a thick tail behind him.

After a moment, there was a hiss: his suit was being sealed off. Then another hiss, and the air turned cold as the special line began to feed air in to him.

The technician gave him his examining instruments. While she drew blood from the child, taking it from a scalp vein, Hall turned his attention to Peter Jackson.

An old man, and pale: anemia. Also thin: first thought, cancer. Second thought, tuberculosis, alcoholism, some other chronic process. And unconscious: he ran through the differential in his mind, from epilepsy to hypoglycemic shock to stroke.

Hall later stated that he felt foolish when the computer provided him with a differential, complete with probabilities of diagnosis. He was not at that time aware of the skill of the computer, the quality of its program.

He checked Jackson’s blood pressure. It was low, 85/50. Pulse fast at 110. Temperature 97.8. Respirations 30 and deep.

He went over the body systematically, beginning with the head and working down. When he produced pain—by pressing on the nerve through the supraorbital notch, just below the eyebrow—the man grimaced and moved his arms to push Hall away.

Perhaps he was not unconscious after all. Perhaps just stuporous. Hall shook him.

“Mr. Jackson. Mr. Jackson.”

The man made no response. And then, slowly, he seemed to revive. Hall shouted his name in his ear and shook him hard.

Peter Jackson opened his eyes, just for a moment, and said, “Go … away …”

Hall continued to shake him, but Jackson relaxed, going limp, his body slipping back to its unresponsive state. Hall gave up, returning to his physical examination. The lungs were clear and the heart seemed normal. There was some tenseness of the abdomen, and Jackson retched once, bringing up some bloody drooling material. Quickly, Hall did a basolyte test for blood: it was positive. He did a rectal exam and tested the stool. It was also positive for blood.

He turned to the technician, who had drawn all the bloods and was feeding the tubes into the computer analysis apparatus in one corner.

“We’ve got a GI bleeder here,” he said. “How soon will the results be back?”

She pointed to a TV screen mounted near the ceiling. “The lab reports are flashed back as soon as they come in. They are displayed there, and on the console in the other room. The easy ones come back first. We should have hematocrit in two minutes.”

Hall waited. The screen glowed, the letters printing out:

JACKSON. PETER

LABORATORY ANALYSES

| TEST | NORMAL | VALUE |

| HEMATOCRIT | 38 – 54 | 21 |

“Half normal,” Hall said. He slapped an oxygen mask on Jackson’s face, fixed the straps, and said, “We’ll need at least four units. Plus two of plasma.”

“I’ll order them.”

“To start as soon as possible.”

She went to phone the blood bank on Level II and asked them to hurry on the requisition. Meantime, Hall turned his attention to the child.

It had been a long time since he had examined an infant, and he had forgotten how difficult it could be. Every time he tried to look at the eyes, the child shut them tightly. Every time he looked down the throat, the child closed his mouth. Every time he tried to listen to the heart, the child shrieked, obscuring all heart sounds.

Yet he persisted, remembering what Stone had said. These two people, dissimilar though they were, nonetheless represented the only survivors of Piedmont. Somehow they had managed to beat the disease. That was a link between the two, between the shriveled old man vomiting blood and the pink young child, howling and screaming.

At first glance, they were as different as possible; they were at opposite ends of the spectrum, sharing nothing in common.

And yet there must be something in common.

It took Hall half an hour to finish his examination of the child. At the end of that time he was forced to conclude that the infant was, to his exam, perfectly normal. Totally normal. Nothing the least bit unusual about him.

Except that, somehow, he had survived.

15

Main Control

STONE SAT WITH LEAVITT in the main control room, looking into the inner room with the capsule. Though cramped, main control was complex and expensive: it had cost $2,000,000, the most costly single room in the Wildfire installation. But it was vital to the functioning of the entire laboratory.

Main control served as the first step in scientific examination of the capsule. Its chief function was detection—the room was geared to detect and isolate microorganisms. According to the Life Analysis Protocol, there were three main steps in the Wildfire program: detection, characterization, and control. First the organism had to be found. Then it had to be studied and understood. Only then could ways be sought to control it.