The Andromeda Strain (18 page)

Read The Andromeda Strain Online

Authors: Michael Crichton

Tags: #Thrillers, #Science Fiction, #Suspense, #High Tech, #Fiction

“What’s this?” Hall said.

“Forty-two-five nutrient. It has everything needed to sustain the average seventy-kilogram man for eighteen hours.”

Hall drank the liquid, which was syrupy and artificially flavored to taste like orange juice. It was a strange sensation, drinking brown orange juice, but not bad after the initial shock. Leavitt explained that it had been developed for the astronauts, and that it contained everything except air-soluble vitamins.

“For that, you need this pill,” he said.

Hall swallowed the pill, then got himself a cup of coffee from a dispenser in the corner. “Any sugar?”

Leavitt shook his head. “No sugar anywhere here. Nothing that might provide a bacterial growth medium. From now on, we’re all on high-protein diets. We’ll make all the sugar we need from the protein breakdown. But we won’t be getting any sugar into the gut. Quite the opposite.”

He reached into his pocket.

“Oh, no.”

“Yes,” Leavitt said. He gave him a small capsule, sealed in aluminum foil.

“No,” Hall said.

“Everyone else has them. Broad-spectrum. Stop by your room and insert it before you go into the final decontamination procedures.”

“I don’t mind dunking myself in all those foul baths,” Hall said. “I don’t mind being irradiated. But I’ll be goddammed—”

“The idea,” Leavitt said, “is that you be as nearly sterile as possible on Level V. We have sterilized your skin and mucous membranes of the respiratory tract as best we can. But we haven’t done a thing about the GI tract yet.”

“Yes,” Hall said, “but suppositories?”

“You’ll get used to it. We’re all taking them for the first four days. Not, of course, that they’ll do any good,” he said, with the familiar wry, pessimistic look on his face. He stood. “Let’s go to the conference room. Stone wants to talk about Karp.”

“Who?”

“Rudolph Karp.”

Rudolph Karp was a Hungarian-born biochemist who came to the United States from England in 1951. He obtained a position at the University of Michigan and worked steadily and quietly for five years. Then, at the suggestion of colleagues at the Ann Arbor observatory, Karp began to investigate meteorites with the intent of determining whether they harbored life, or showed evidence of having done so in the past. He took the proposal quite seriously and worked with diligence, writing no papers on the subject until the early 1960’s, when Calvin and Vaughn and Nagy and others were writing explosive papers on similar subjects.

The arguments and counter-arguments were complex, but boiled down to a simple substrate: whenever a worker would announce that he had found a fossil, or a proteinaceous hydrocarbon, or other indication of life within a meteorite, the critics would claim sloppy lab technique and contamination with earth-origin matter and organisms.

Karp, with his careful, slow techniques, was determined to end the arguments once and for all. He announced that he had taken great pains to avoid contamination: each meterorite he examined had been washed in twelve solutions, including peroxide, iodine, hypertonic saline and dilute acids. It was then exposed to intense ultraviolet light for a period of two days. Finally, it was submerged in a germicidal solution and placed in a germ-free, sterile isolation chamber; further work was done within the chamber.

Karp, upon breaking open his meteorites, was able to isolate bacteria. He found that they were ring-shaped organisms, rather like a tiny undulating inner tube, and he found they could grow and multiply. He claimed that, while they were essentially similar to earthly bacteria in structure, being based upon proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids, they had no cell nucleus and therefore their manner of propagation was a mystery.

Karp presented his information in his usual quiet, unsensational manner, and hoped for a good reception. He did not receive one; instead, he was laughed down by the Seventh Conference of Astrophysics and Geophysics, meeting in London in 1961. He became discouraged and set his work with meteorites aside; the organisms were later destroyed in an accidental laboratory explosion on the night of June 27, 1963.

Karp’s experience was almost identical to that of Nagy and the others. Scientists in the 1960’s were not willing to entertain notions of life existing in meteorites; all evidence presented was discounted, dismissed, and ignored.

A handful of people in a dozen countries remained intrigued, however. One of them was Jeremy Stone; another was Peter Leavitt. It was Leavitt who, some years before, had formulated the Rule of 48. The Rule of 48 was intended as a humorous reminder to scientists, and referred to the massive literature collected in the late 1940’s and the 1950’s concerning the human chromosome number.

For years it was stated that men had forty-eight chromosomes in their cells; there were pictures to prove it, and any number of careful studies. In 1953, a group of American researchers announced to the world that the human chromosome number was forty-six. Once more, there were pictures to prove it, and studies to confirm it. But these researchers also went back to reexamine the old pictures, and the old studies—and found only forty-six chromosomes, not forty-eight.

Leavitt’s Rule of 48 said simply, “All Scientists Are Blind.” And Leavitt had invoked his rule when he saw the reception Karp and others received. Leavitt went over the reports and the papers and found no reason to reject the meteorite studies out of hand; many of the experiments were careful, well reasoned, and compelling.

He remembered this when he and the other Wildfire planners drew up the study known as the Vector Three. Along with the Toxic Five, it formed one of the firm theoretical bases for Wildfire.

The Vector Three was a report that considered a crucial question: If a bacterium invaded the earth, causing a new disease, where would that bacterium come from?

After consultation with astronomers and evolutionary theories, the Wildfire group concluded that bacteria could come from three sources.

The first was the most obvious—an organism, from another planet or galaxy, which had the protection to survive the extremes of temperature and vacuum that existed in space. There was no doubt that organisms could survive—there was, for instance, a class of bacteria known as thermophilic that thrived on extreme heat, multiplying enthusiastically in temperatures as high as 70°C. Further, it was known that bacteria had been recovered from Egyptian tombs, where they had been sealed for thousands of years. These bacteria were still viable.

The secret lay in the bacteria’s ability to form spores, molding a hard calcific shell around themselves. This shell enabled the organism to survive freezing or boiling, and, if necessary, thousands of years without food. It combined all the advantages of a space suit with those of suspended animation.

There was no doubt that a spore could travel through space. But was another planet or galaxy the most

likely

source of contamination for the earth?

Here, the answer was no. The most likely source was the closest source—the earth itself.

The report suggested that bacteria could have left the surface of the earth eons ago, when life was just beginning to emerge from the oceans and the hot, baked continents. Such bacteria would depart before the fishes, before the primitive mammals, long before the first ape-man. The bacteria would head up into the air, and slowly ascend until they were literally in space. Once there, they might evolve into unusual forms, perhaps even learning to derive energy for life directly from the sun, instead of requiring food as an energy source. These organisms might also be capable of direct conversion of energy to matter.

Leavitt himself suggested the analogy of the upper atmosphere and the depths of the sea as equally inhospitable environments, but equally viable. In the deepest, blackest regions of the oceans, where oxygenation was poor, and where light never reached, life forms were known to exist in abundance. Why not also in the far reaches of the atmosphere? True, oxygen was scarce. True, food hardly existed. But if creatures could live miles beneath the surface, why could they not also live five miles above it?

And if there were organisms out there, and if they had departed from the baking crust of the earth long before the first men appeared, then they would be foreign to man. No immunity, no adaptation, no antibodies would have been developed. They would be primitive aliens to modern man, in the same way that the shark, a primitive fish unchanged for a hundred million years, was alien and dangerous to modern man, invading the oceans for the first time.

The third source of contamination, the third of the vectors, was at the same time the most likely and the most troublesome. This was contemporary earth organisms, taken into space by inadequately sterilized spacecraft. Once in space, the organisms would be exposed to harsh radiation, weightlessness, and other environmental forces that might exert a mutagenic effect, altering the organisms.

So that when they came down, they would be different.

Take up a harmless bacteria—such as the organism that causes pimples, or sore throats—and bring it back in a new form, virulent and unexpected. It might do anything. It might show a preference for the aqueous humor of the inner eye, and invade the eyeball. It might thrive on the acid secretions of the stomach. It might multiply on the small currents of electricity afforded by the human brain itself, drive men mad.

This whole idea of mutated bacteria seemed farfetched and unlikely to the Wildfire people. It is ironic that this should be the case, particularly in view of what happened to the Andromeda Strain. But the Wildfire team staunchly ignored both the evidence of their own experience—that bacteria mutate rapidly and radically—and the evidence of the Biosatellite tests, in which a series of earth forms were sent into space and later recovered.

Biosatellite II contained, among other things, several species of bacteria. It was later reported that the bacteria had reproduced at a rate twenty to thirty times normal. The reasons were still unclear, but the results unequivocal: space could affect reproduction and growth.

And yet no one in Wildfire paid attention to this fact, until it was too late.

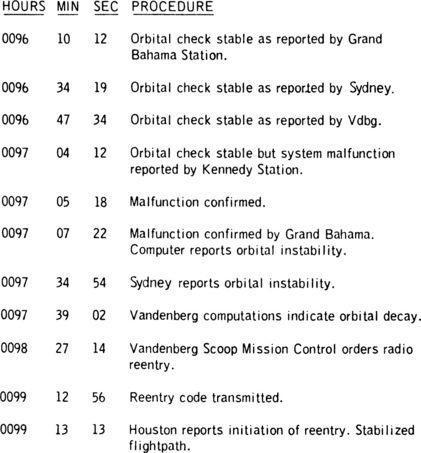

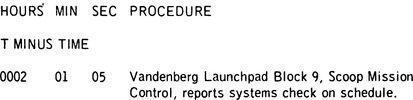

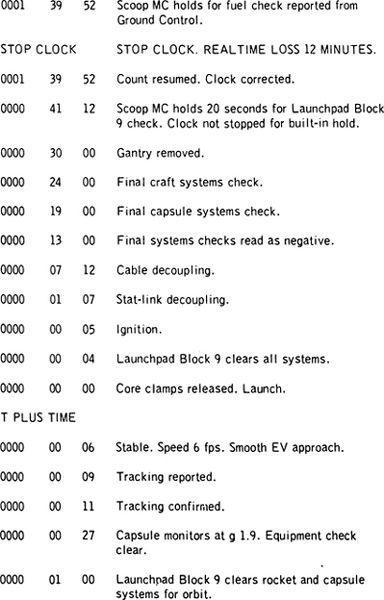

Stone reviewed the information quickly, then handed each of them a cardboard file. “These files,” he said, “contain a transcript of autoclock records of the entire flight of Scoop VII. Our purpose in reviewing the transcript is to determine, if possible, what happened to the satellite while it was in orbit.”

Hall said, “Something happened to it?”

Leavitt explained. “The satellite was scheduled for a six-day orbit, since the probability of collecting organisms is proportional to time in orbit. After launch, it was in stable orbit. Then, on the second day, it went out of orbit.”

Hall nodded.

“Start,” Stone said, “with the first page.”

Hall opened his file.

AUTOCLOCK TRANSCRIPT

PROJECT: SCOOP VII

LAUNCHDATE:

ABRIDGED VERSION. FULL TRANSCRIPT

STORED VAULTS 179-99, VDBG COMPLEX

EPSILON.

“No point in dwelling on this,” Stone said. “It is the record of a perfect launch. There is nothing here, in fact, nothing for the next ninety-six hours of flight, to indicate any difficulty on board the spacecraft. Now turn to page 10.”

They all turned.

TRACK TRANSCRIPT CONT’D

SCOOP VII

LAUNCHDATE: –

ABRIDGED VERSION