The Adventure of English (22 page)

Read The Adventure of English Online

Authors: Melvyn Bragg

The American cowboys themselves joined in. “Cow-poke,” “cowhand,” “cow-puncher,” “wrangler,” “range-rider,” “bronco-buster,” “hot under the collar” and “bite the dust” all came from the men on horses themselves. “Rustler” was an American word from the imitative verb “rustle”: the cowboys pinched it for “cattle-thief.” Samuel Maverick was unique in his refusal to brand his cattle because he thought it was cruel. (His detractors thought it was because he could thereby claim all unbranded cattle as his own.) The “maverick” is his legacy.

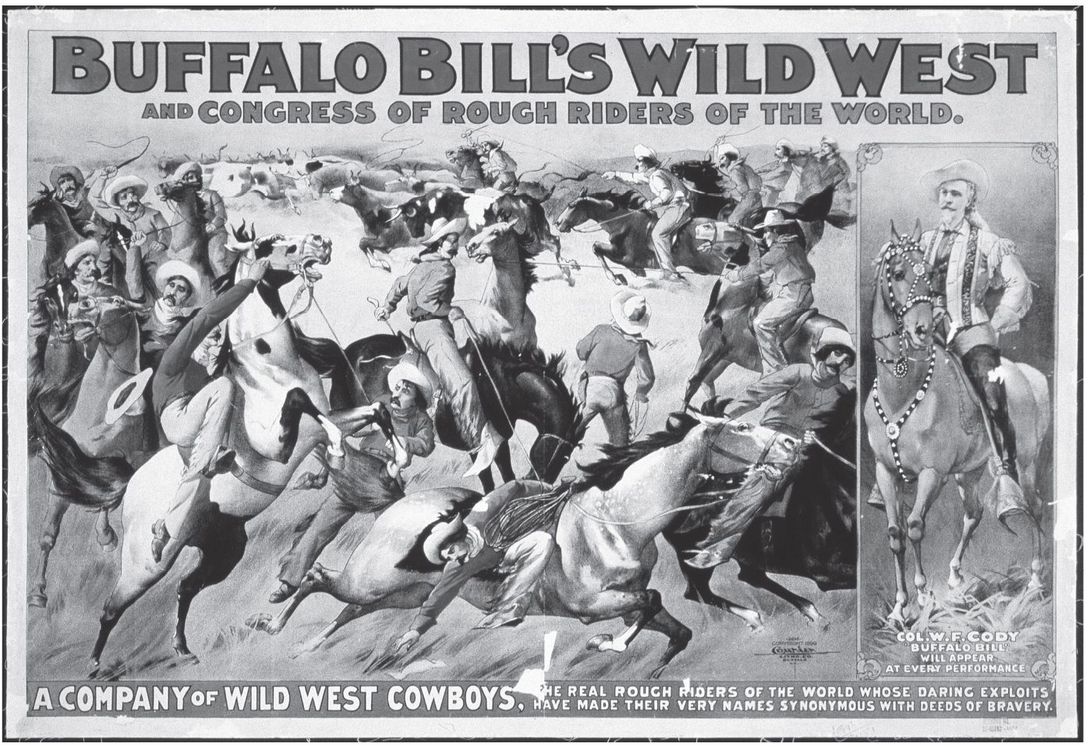

The cowboys then took over the entertainment business and spread their words, their lives, their history and their fantasies around a dumbstruck world. It began in a circus tent and it was dreamed up and booted into life by a real cowboy, William F. Cody, turned great showman, Buffalo Bill.

Buffalo Bill's

Wild West

was a rip-roaring success across America and Europe for thirty years. It staged dramatic fights with real Native Americans attacking a stagecoach long after Native American resistance had finally been crushed. Live buffaloes were still pursued around the ring by the Native Americans and Buffalo Bill on his white horse long after almost all the buffalo had been massacred and the last native had been herded on to a dismal reservation. It was nonsense and it was a smash hit. Queen Victoria attended a performance in London, the first British monarch publicly to acknowledge America since the Revolution. Custer's Last Stand at Little Big Horn was the climax.

Soon there were singing cowboys, sharp-shooting cowboys, lassoing cowboys and trick-riding cowboys. Painters, writers, newspaper columnists, all piled into this gold mine. And when the cinema came, the cowboys rode into celluloid, deep into the twentieth century and into the minds and hearts of millions and millions of children who, like myself, galloped down our streets after these films, sat astride imaginary horses, shot imaginary guns at imaginary Native Americans, trying to look like and sound like our cowboy heroes, swept into the everyday epic of the American plains.

It was golden. It was a British dream as well as an American. It spoke to us, and in our own language, or was it their language now? And it had no problems a decent man with a sure hold on the truth and his Colt 45 could not resolve.

But back on the Mississippi another expression came in: “sold down the river.” It derives from the way unruly slaves from the plantations would be sold on to owners further downriver where conditions were supposed to be worse. The slaves had their language too.

Sold Down the River

I

f you can imagine a language having a life of its own, exploring new territories as individuals have explored new territories, taking punishment and being blocked, damaged and imprisoned as individuals have been and are; that language after a certain take-off stage becomes a living entity, like water, a spring, a stream, a river; then the reach of English has been oceanic. It had already, by this stage in its history, the middle of the eighteenth century, gone from a splinter dialect of a subdivision of a branch of an Indo-European tongue to the language of Shakespeare and the King James Bible, the language that sailed in the mouths and minds of zealous and dedicated men and women to plant itself in a new world. Yet of all its many triumphs and cunningly rich compromises, there is little, I think, that so singularly characterises its resources as its encounter with the African languages through the slave trade.

That English united and absorbed so many scores of African tongues and so quickly, that it was itself sufficiently pliable and yielding to receive back the raft of words, phrases and insights brought from cultures so very different, is awesome. For English was able to perform an act of symbiosis with tribal tongues from a wholly different language group, even to survive being taken on by an alien grammatical system. This began to gather strength in the eighteenth century and went on to create a new English, black English, which fed back into the mainstream, especially in the twentieth century.

The terrible fate and journey of African slaves has been told many times and needs to be: the hundreds of miles they were force-marched across Africa by the African slavers; the inhuman packaging on the ships for the Middle Passage which the western European seaboard nations forced on them to take them as cheaply as possible to the New World; the sales, the deaths, injustices, branding, sale, exploitation, flogging, dehumanisation; the trade was ended by the country, England, which had come to it last, had been, probably, the most prolific in its commerce, but at least left first after 1807 when the British Parliament abolished the slave trade and the British navy spent decades enforcing that ruling.

Black English, against what must have seemed all the odds, had emerged in triumph by the twentieth century, and with breathtaking irony, it became the key vocabulary in many of the arts of pleasure. English today the world over is laced with words and expressions which came from those to whom for centuries words alone “were certain good.”

The English which came to the eastern seaboard with the

Mayflower

and its progeny was an English determined to settle as the language of the land, proud to be English, ample in the great globe of the language, soon enough challenging London and proclaiming New England the chief guarantor of true English. The less regulated citizens who went west and further west, the Scots and Irish in their assault on the wild frontier, borrowed words from all over the place: from the Native Americans, the wildernesses, other European nations and above all the necessity to put into words the astonishing new sites and sights in nature itself. They invented new words and brought an Elizabethan trawl to the table. Now in the south, there entered peoples on whose influence on the language nobody would have bet a penny, but they dug into this alien tongue with their own inheritance, and the combined language delivered â a common tongue for them and an uncommon fresh word-hoard for English. I suppose I think that if English could do this and have this done to it, if it could become the instrument even of those it sought to suppress and come out of the encounter so much in credit, then it can be called a language fit for world service.

Between a half and two-thirds of the black slaves who were transported to America arrived in Charleston in South Carolina â Sullivan's Island has been called the Ellis Island of black America. Ellis Island is proudly and significantly made iconic by the Statue of Liberty and the movingly inscribed promise of a new life for the tired, the poor and the huddled masses of the world. There is no statue, no great memorial, no magnificent declaration of hope and welcome on Sullivan's Island where tired, poor and huddled masses also came. There is a plaque, put up in 1998.

Near Charleston there can still be heard a local dialect, called Gullah, which is believed to be close to the English spoken by the African forced immigrants soon after they were put to work, generally on the plantations. It is thought that “Gullah” probably derives from Angola. The Africans came via the West Indies or directly from West Africa where there were several

hundred

local languages, including Hausa, Wolof, Bulu, Bamoun, Temne, Asante and Twi. The policy on board ship was to break up groups of speakers of any one language; the idea being that if the slaves could not talk to each other in large numbers they would find it difficult to organise effective resistance. Captain William Smith, in 1744, in his book

A New Voyage to Guinea,

wrote that “by having some of every sort on board, there will be more likelihood of their succeeding in a plot, than of finishing the Tower of Babel.”

In order to communicate with each other, the slaves had to find a common language. There were two on offer, neither one their own. The first was what could be termed a Mediterranean lingua franca, used by multinational, multilingual naval crews, called Sabir. It dates back to the Crusades, may be French- or Spanish-based and is thought to be the source of West Indian pidgin and English words like “pickaninny” (pequeno, Portuguese, small) and “savvy” (most likely from Spanish).

The second language available was English, and a pidgin form of English developed with remarkable speed often on board ship itself, which is hard to credit given the coffined and confined nature of the unspeakable accommodation on the Middle Passage. But as Robert McCrum pointed out, “most Africans would know at least three languages.” It would not be unusual for them to know six. “They are,” he claimed, “among the most accomplished linguists in the world.” And that cramped state yielded a new dialect, a pidgin form of English which developed further when they came on shore. (“Pidgin” is a word derived from the Chinese pronunciation of the English word “business.” “Pidgin” is a language with no native speakers, one constructed for communication between people with no common language.)

25. Contact between the Pilgrim Fathers and the Native Americans led to only a few Native American words entering the English language â but the settlers coined many new words for the unexpected new sights around them.

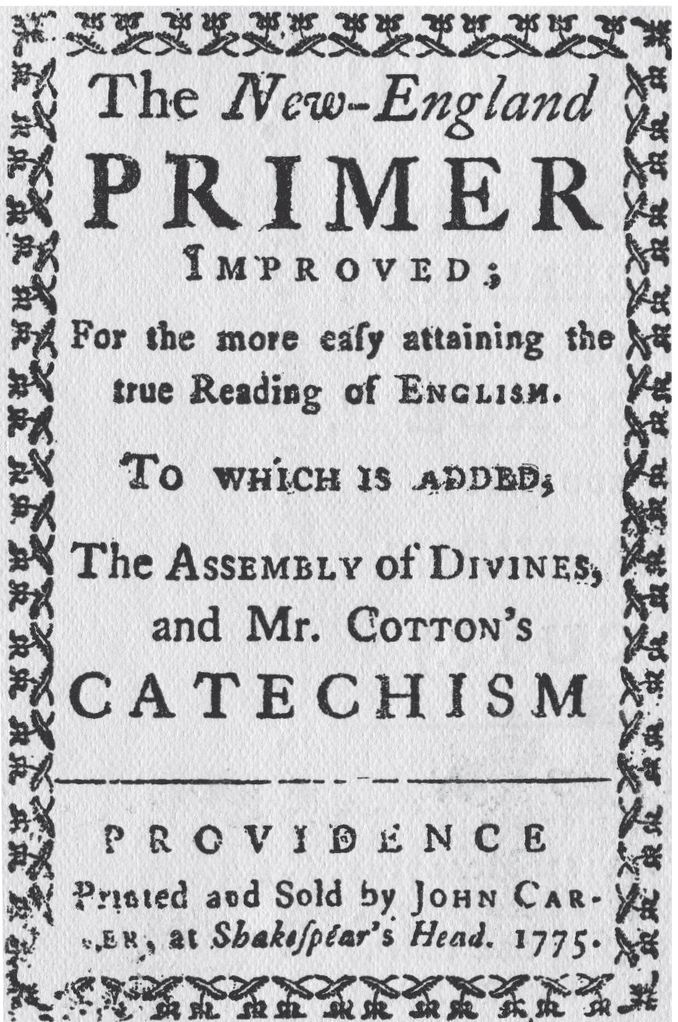

26.

The New England Primer,

an elementary textbook, sold over three million copies in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

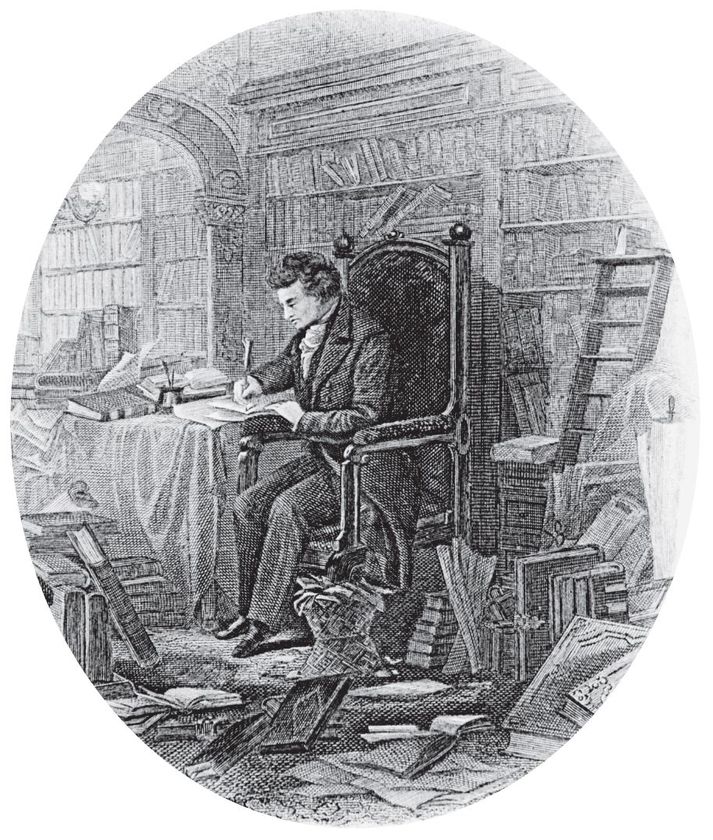

27. Noah Webster at work on his dictionary of 1828, believed that “the people of one quarter of the world will be able to converse together like the children of one family.”

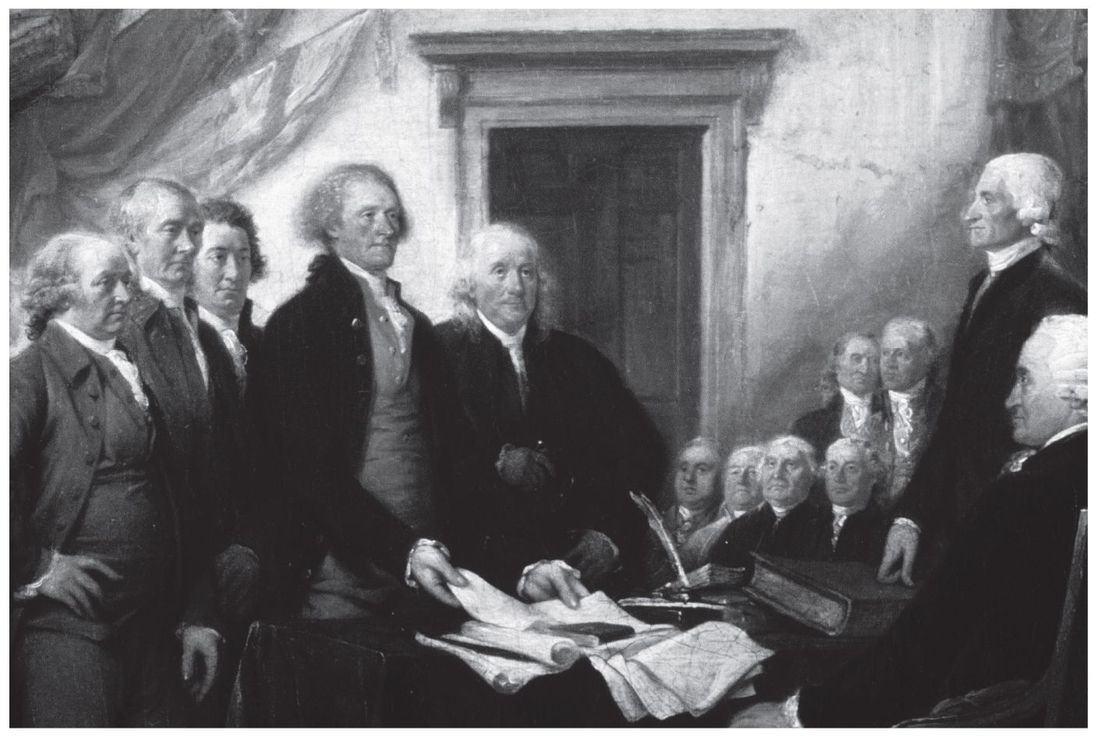

28. On July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence, a masterpiece of English prose, was signed. In 1780 John Adams, the second U.S. President, wrote: “English is destined to be in the next and succeeding centuries more generally the language of the world.”

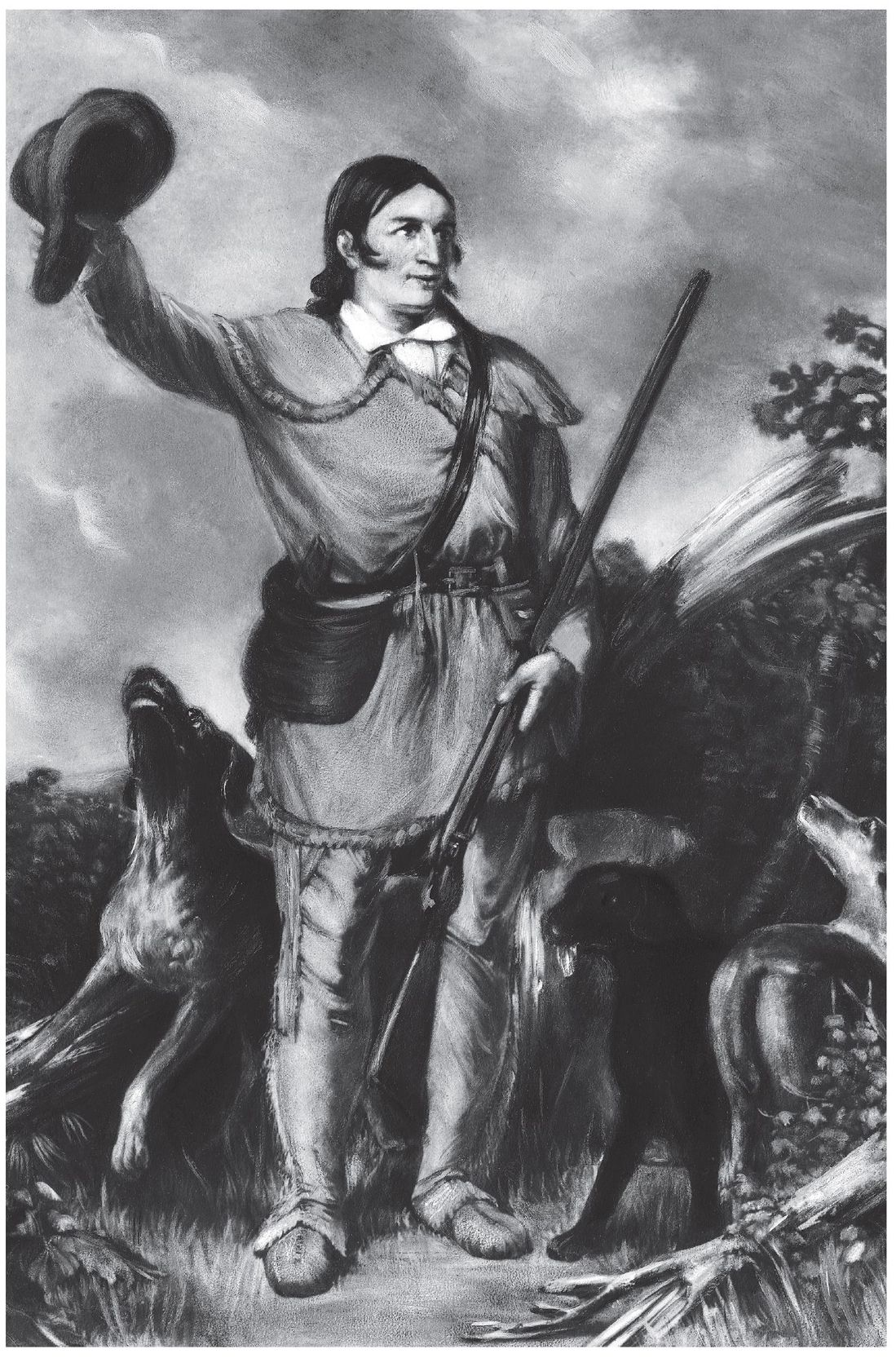

29. Frontiersman Davy Crockett, “King of the Wild Frontier,” became a Congressman and was one of the first exponents of “Tall Talk” â using new words like “skedaddle,” “hunky-dory” and “splendiferous.”

30. Buffalo Bill's Wild West show spread the language and image of the cowboy around the world.

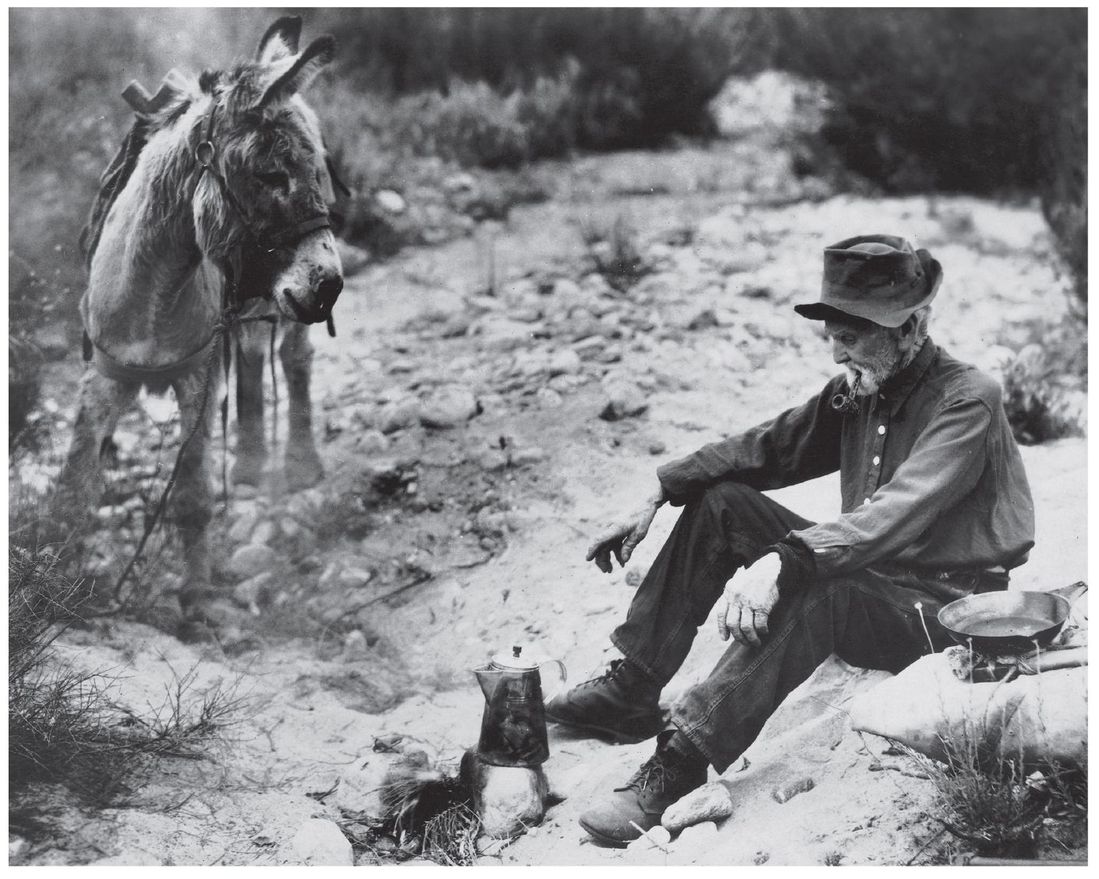

31. The “gold rush” brought even more people to the West, with a new vocabulary of “prospecting,” “panning” and “staking a claim”; Levi Strauss made hard-wearing clothes for them, so Levis and jeans were born.